Let’s take a moment today to reflect a few messages George Mills sent out into the world without knowing who might read them. His books were primarily for children, but the same can't be said for the dedications and prefaces of his texts: They were meant for persons other than schoolboys.

Taking a look at these brief but meaningful messages within the books—but not part of the stories themselves—may tell us something.

Or they may simply let us know how much more we may want to know.

The 1930s:

• First let's look at the preface of 1933's first edition of Meredith & Co.:

ALTHOUGH all the incidents in this book, with the exception of the 'bait charts,' are imaginary, the book gives an accurate impression of life in a Boys' Preparatory School.

I wish to acknowledge, with much gratitude, the help and encouragement received from many friends; particularly from Mr. A. Bishop, the Head Master of Magdalen College School, Brackley, and from my old friend, Mr. H. E. Howell, who have read the book in manuscript form. I am also much indebted to Mr. E. M. Henshaw for his devastating, but most useful, criticisms, and especially to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material.

----------------------------------------------------------- G.M.

We've examined fairly recently the life and career of Mr. A. Bishop—Arthur Henry Burdick Bishop [right]—and have seen some references to Mr. H. E. Howell, although we have no real idea who he was.

We've examined fairly recently the life and career of Mr. A. Bishop—Arthur Henry Burdick Bishop [right]—and have seen some references to Mr. H. E. Howell, although we have no real idea who he was.The annoyingly critical Mr. E. M. Henshaw—whose mention was deleted from subsequent editions of Meredith—has so far been difficult to identify. Henshaw must have been an unliked and unwanted obligation, one that in later years no longer needed to appear.

Once again, if you have any notion of Henshaw's identity, or have some clever skills in a database like ancestry.com or The Times, please don't hesitate to let me know!

• Next, we'll examine the dedication to the 1933 edition of Meredith & Co.:

of Warren Hill, Eastbourne; to the STAFF AND

BOYS OF THE SAME SCHOOL, and to those of

WINDLESHAM HOUSE, BRIGHTON, THE CRAIG,

WINDERMERE, and the ENGLISH PREPARATORY

SCHOOL, GLION, among whom I spent many

happy years, this book is affectionately

dedicated.

We've had far more luck tracing our way through this dedication. http://www.blogger.com/img/blank.gif

We've had far more luck tracing our way through this dedication. http://www.blogger.com/img/blank.gifOver time, we've been enlightened by Dr. Tom Houston at Windlesham and tracked down a smattering of information about The Craig and the English Preparatory School at Glion.

The amount of information we've unearthed about both Joshua Goodland, a mentor of George Mills, and Warren Hill School in Eastbourne [left], seems comparatively to be a wealth of knowledge!

• Mills's next published book was 1938's King Willow. Let's look at its preface:

READERS of Meredith & Co. will recognize here some old friends ; nevertheless King Willow can be read as an entirely independent story. The characters have no connexion with any people, alive of dead, but the book is typical of life in any big Preparatory School.

Once More I wish to record my thanks to my friend, Mr H. E. Howell, who has read the manuscript and offered helpful criticism ; and also to a host of schoolboy readers who have encouraged me to continue.

------------------------------------------------------------- G.M.

June, 1938

Again, by June, 1938, the mysterious Mr. H. E. Howell remains a dear friend of George Mills, schoolmaster and author.

• Let's look at the 1938 dedication to King Willow:

THE HEADMASTERS, STAFF, AND BOYS

OF

EATON GATE PREPARATORY SCHOOL,

LONDON, S.W. 1.

That's a rather all-encompassing dedication. We have discussed the fact that no school by that name has been found (although I would be delighted to be corrected), and the current school at that location has no real interest in exploring its own past or in assisting in educational research.

It's interesting that Mills misnames the school, yet is precise enough to include the location "S.W.1." It's also noteworthy in that, while it must be the most recent school at which he'd worked, Mills singles out no Headmaster or Principal by name. Might that indicate he had already severed ties with the institution, and under less than joyful circumstances?

These inconsistencies make this is by far the strangest of Mills's prefaces or dedications.

• Now we'll examine the 1939 preface of Minor and Major:

THIS book deals with life in a big preparatory school, and tells about the boys and masters, their goings-out and their comings-in. All the characters are imaginary, and no allusion is meant to any living person.

The boys, who first appeared in Meredith & Co. and King Willow, once again present themselves for a short time during a cricket match.

I wish to record my thanks to my old friend, Mr H. E. Howell, for so kindly reading the manuscript and proofs. I also recognize the kindly aid of a schoolboy, Terence Hadow, whose criticisms have been invaluable, as also has the encouragement given to me by my friend, Mr Egerton Clarke, who has read the book in manuscript form. My thanks are also due to Mr A. L. Mackie, who has kindly helped to read the proofs.

------------------------------------------------------------- G.M.

Mills for a third time pays tribute to "old friend" Howell, but this time extends thanks to a few more individuals.

Mills for a third time pays tribute to "old friend" Howell, but this time extends thanks to a few more individuals.Schoolboy critic Terence Hadow died in 1942 serving as a chindit[some are pictured in Burma, right] under Major-General Orde Wingate. His remains were interred in Burma.

Egerton Clarke, as we recently learned, was a friend of George's in the Army Pay Corps, and at Oxford before leading George to the publishing house that would print Mills's final new book in 1939. Egerton passed away in 1944.

Finally, we simply do not know the identity of the kindly Mr. A. L. Mackie. Once again, if you have any idea, please let me know!

• Moving along, we arrive at 1939's dedication to Minor and Major:

Parkfield, Haywards Heath, where I received

my early education, this book is affectionately

dedicated

For the first time, Mills takes a nostalgic bent in creating a dedication, hearkening back to the first decade of the 20th century in dedicating Minor and Major to his own masters, as well as the boys with whom he attended Parkfield.

Parkfield is a school we've located and learned about to some degree after hearing from alumni.

The 1950s:

The prep school books of George Mills all were reprinted, Meredith and Co. twice.

• The edition we'll look at here is from 1950, published by Oxford University Press.

In addition to the preface and dedication found in the first edition, Mills, as we know, added this verse by Rudyard Kipling [left]:

In addition to the preface and dedication found in the first edition, Mills, as we know, added this verse by Rudyard Kipling [left]:Give me a willow wand, and I

With hide and cork and twine,

From century to century,

Will gambol round thy shrine

------------- —Kipling

There is also a subtle change in the preface. The last sentence of the 1933 original reads:

I am also much indebted to Mr. E. M. Henshaw for his devastating, but most useful, criticisms, and especially to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material.

The 1950 version simply reads:

I am also much indebted to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material.

Oxford University Press kept no records from that era, so we have no way of knowing if Henshaw was associated with the company in 1933, but had passed away or moved his career to another locale by 1950. Hence, the expression of gratitude to person for whom it's likely Mills cared very little was no longer necessary

• Jumping ahead to the late 1950s and the undated edition of King Willow, we find this revised dedication:

BERYL and IAN

Two young people who have just set

out on a long voyage in the good ship

Matrimony. May they have smooth

seas and following winds: may they

from time to time take aboard some

young passengers who will become

the light of their lives until they sail

into the last harbor.

Here George looks back on his life in the context of looking ahead to the lives of this young couple. He reflects on growing old together—something George was himself unable to do with his own wife, Vera, who died 30 years before he did. George and Vera passed away childless, and there is more than a little melancholy in Mills's best wishes for for the couple to be blessed with children.

Despite help from Michael Downes in Budleigh Salterton via his blog, we still have been unable to determine the identity of the newlyweds, Beryl & Ian, who probably would have been born between 1930 and 1940, and would be 70 or 80 years of age by now.

If you know Beryl & Ian, or if you actually are Beryl & Ian, please let me know!

• The 1950s edition of King Willow of also contains an expanded preface:

READERS of Meredith & Co. will recognize here some old friends ; nevertheless King Willow can be read as an entirely independent story. The characters have no connexion with any people, alive of dead, but the book is typical of life in any big Preparatory School.

Once More I wish to record my thanks to my friend, Mr H. E. Howell, who has read the manuscript and offered helpful criticism ; and also to a host of schoolboy readers who have encouraged me to continue.

I also wish to record my thanks to Benedict Thomas, a schoolboy who has suggested many practical alterations for this new edition.

---------------------------------------------------- G.M.

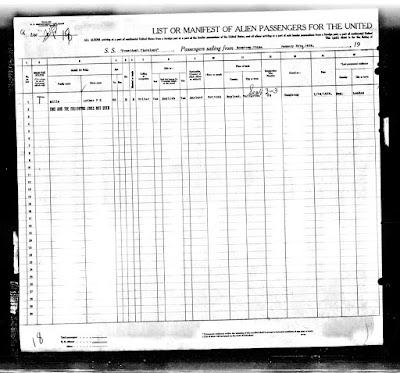

Here we meet a youthful Benedict Thomas, a lad who was helping an approximately 60 year old George Mills with his latest reprint of King Willow.

The only person of that name born in the U. K. between 1940 and 1960 was a "Benedict J. G. Thomas," who was born in late 1953. If Willow was published in 1960, Benedict would have been about 8 years of age when he offered his practical advice to Mills.

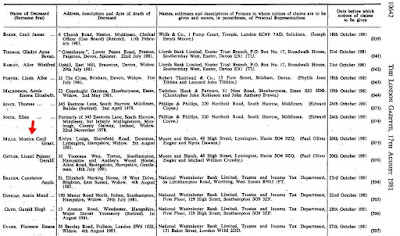

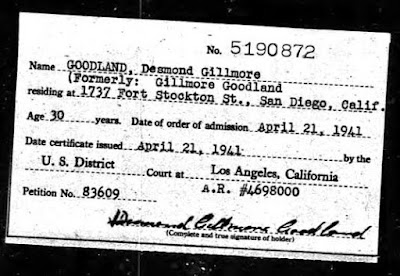

The only person of that name born in the U. K. between 1940 and 1960 was a "Benedict J. G. Thomas," who was born in late 1953. If Willow was published in 1960, Benedict would have been about 8 years of age when he offered his practical advice to Mills.The only record at ancestry.com involving a Benedict J. G. Thomas involves his birth—nothing else. There is a location—Northeastern Surrey—and one other interesting bit of information: Benedict's mother's maiden name was Bishop.

That could make young Benedict the grandson of Arthur H. B. Bishop, mentioned in the first preface of George's first book. It would indicate that Mill's friendship with Bishop was long-lasting, but it could also indicate that the aging Mills may have been teaching or living in or near Surrey.

• The 1950s-ish edition of Minor and Major has the same dedication as the original in 1939, but has omitted the original preface seen above.

But there is this, in italic font:

are imaginary, and no allusion

is meant to any living person.

Did the publisher, London's Spring Books, include that as matter of course in all fiction books printed in that year? If so, that would provide evidence that the reprinting of Minor and Major was, indeed, the last of the late 1950s – early 1960s reprints. If not, could it be that a schoolboy, schoolmaster, or even headmaster from back in George's past had an issue with a character, thinking it Mils had taken a slap at him?

We'll never know if the latter was the case, but it seems that as the world approached our seemingly increasingly litigious times, that disclaimer may have been inserted across the proverbial board.

The Missing Text:

There is only one bit of information I have been unable to uncover: What might we find in the dedication and/or preface to Mills's final book, Saint Thomas of Canterbury, published in 1939 by Burns, Oates and Washbourne, the Catholic publishing house in London.

There is only one bit of information I have been unable to uncover: What might we find in the dedication and/or preface to Mills's final book, Saint Thomas of Canterbury, published in 1939 by Burns, Oates and Washbourne, the Catholic publishing house in London.A glimpse of what is there could be most informative. One wonders if—given it was Mills's 'swan song' as an author—there might have been some clue in a dedication or preface that would provide insight as to why he never penned another book. Although I frequently check booksellers around the world, a copy of this title simpy hasn't arisen, and the closest library copy to here is about 600 miles away! It may be some time before we get the very last of the messages of George Mills...

As we wind our way down to the last few topics regarding George Mills that I have left to write, many thanks once again to everyone who has contributed in an effort to help me answer the question: Who Is George Mills?

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)