For today's adventure in reading antique newspaper print, I thought I'd continue to turn over the fertile soil of the London Gazette looking for information about George Mills' half-brother, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills. There wasn't a lot, but it turned up some interesting facts.

First off, from the 18 September 1908 issue:

INFANTRY.

The Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, in succession to Lieutenant F. H. Span, seconded.

1908 was the year Arthur told his publisher at the time, Evans Brothers, that he had been "gazetted" into the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry. We do know from Sandhurst that the date of his actual commission had been the next day, 19 September 1908. Was "gazetted" a term meaning that the news had appeared first in the London Gazette?

The next we read of Arthur is in the Gazette's 3 February 1914 issue:

GENERAL RESERVE OF OFFICERS.

INFANTRY.

The Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, late lieutenant, with seniority as from 26th July, 1912. Dated 4th February 1914.

Now, wording can be awfully difficult stuff to look up on the internet for interpretation. Has he become a lieutenant here, or was he a lieutenant of late and now is at this point being promoted upward?

And here's an interesting Gazette listing, Arthur's entry being amid a flock of other names, dated a full 25 years later, in the 12 December 1939 issue:

ROYAL ARMY SERVICE CORPS.

SPECIAL LIST.

The undermentioned, from the Army Officers' Emergency Reserve, to be 2nd Lts. 2nd September 1939:—

A. F. H. Mills (98184)

So we find that Arthur, some quarter of a century removed from having been wounded in France, was returning to duty at the age of 52. We found out yesterday that George would follow in less than a year. Interestingly, Arthur left the military at some earlier point having achieved the rank of Captain. George left as a Lance Corporal in 1919. But they'd both return as Lieutenants as World War II was beginning.

We then find three consecutive entries referring to Arthur in just one section of the Gazette dated 1 March 1940:

SPECIAL LIST.

The personal number of Lt. A. F. H. Mills is 43673, and not as notified in the Gazette of 15th December 1939.

The notifn. regarding Maj. A. F. MILLS (43673) in the Gazette of 9th Sept. 1939 is cancelled.

Lt. Arthur Frederick Hobart MILLS (43673) relinquishes his comm. 10th Sept. 1939.

I've searched extensively through the London Gazette's website using their Byzantine system, but there simply are no issues dated 9th September 1939, and I can't seem to find any additional references to Arthur Mills anywhere, in 1939 or not, except this one:

Name of Deceased (Surname First)

MILLS, Arthur Frederick Hobart

Address, description and date of death of Deceased

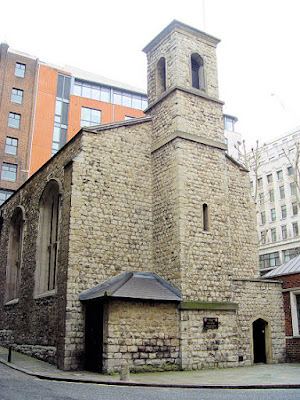

Winds Cottage, Downton [pictured, right], near Lymington, Hampshire, formerly of Stable Cottage, Hurst Wickham, Hassocks, Sussex, Captain H.M. Army (Retired), 18th February, 1955

Winds Cottage, Downton [pictured, right], near Lymington, Hampshire, formerly of Stable Cottage, Hurst Wickham, Hassocks, Sussex, Captain H.M. Army (Retired), 18th February, 1955Names, addresses, and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives

Hunters, 9, New Square, Lincoln's Inn, London, W.C.2, solicitors. (Hugh Murchison Clowes)

Date on or before which notices of claim to be given

8th September, 1955 (283)

That's quite a lot of information regarding the demise of Arthur F. H. Mills. But I wish we knew more about his life from 1939 to 1955.

A couple of things do jump out at me. First, in the second citation on 1 March 1940, Arthur's rank is listed as "Maj." Is it safe for me to assume that he may have been elevated in rank from Lieutenant to Major somewhere in early September only to have it cancelled?

Also, if I'm reading things correctly, he was reinstated from the Army Officers' Emergency Reserve on 2 September 1939, but almost immediately relinquished his commission on 10 September. Apparently, during those 8 days—possibly on the 9th—a promotion had been announced and subsequently rescinded the next day. What an interesting week that must have been...

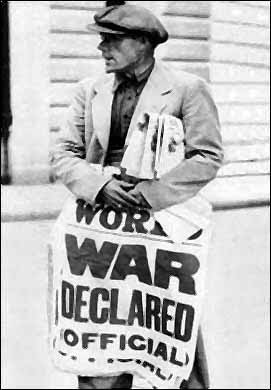

I'll admit, when I think of the onset of the Second World War, I imagine it beginning with a standing army of well-trained troops from Britain being bolstered by an influx of strong, young men and women joining the cause. In the last two days, however, we've seen Arthur Mills—age 52—returning to his military roots, albeit briefly, just one day before Great Britain officially declared war on Germany, Sunday 3 September 1939. George enters the fray a year later, at 44 years of age.

I'll admit, when I think of the onset of the Second World War, I imagine it beginning with a standing army of well-trained troops from Britain being bolstered by an influx of strong, young men and women joining the cause. In the last two days, however, we've seen Arthur Mills—age 52—returning to his military roots, albeit briefly, just one day before Great Britain officially declared war on Germany, Sunday 3 September 1939. George enters the fray a year later, at 44 years of age.These must have been confusing times. By that Sunday, the 3rd, the Wehrmacht had unleashed two days of blitzkrieg on Poland. HMS Courageous and HMS Royal Oak would soon be sunk by u-boats. And by the time George Mills returned to the military on 11 October 1940, the Luftwaffe had at last crossed the channel and attacked British warships at Firth of Forth. All of these events had been and were being played out against the backdrop of the drama leading up to the Norway Debate in Parliament, and in its wake, the resignation of Neville Chamberlain and succession of Winston Churchill.

We have the luxury of putting all of this in perspective using hindsight, though. At the time, a populace being called on to sacrifice again had already endured a World War just two decades before would have been bracing itself for yet another global conflict—and one in which technological advances had burgeoned so quickly that long range bombers and rockets would present a danger never before experienced. Given the labile emotional, technological, and political landscape of 1939-1940, did anyone really know exactly what to expect in the long term?

Were the Mills brothers, Arthur and George, patriotic citizens who saw their country in need and wanted almost immediately to help, despite their relatively advanced ages? Or was the War Office anticipating the need for able-bodied young men in the various theatres of war abroad, and doing its best to draw upon a pantry full of veterans who would have been able to stock many military positions on the home front while younger fighting men were steadily sent overseas?

Were the Mills brothers, Arthur and George, patriotic citizens who saw their country in need and wanted almost immediately to help, despite their relatively advanced ages? Or was the War Office anticipating the need for able-bodied young men in the various theatres of war abroad, and doing its best to draw upon a pantry full of veterans who would have been able to stock many military positions on the home front while younger fighting men were steadily sent overseas?It's interesting to note that Arthur F. H. Mills published his novel White Negro in 1940. He'd published at the very least one novel per year since 1921, while also writing short stories for periodicals. That particular book, however, would the last one he would publish until 1947's Don't Touch the Body—unless there were texts written and published in between that I simply cannot find record of anywhere.

Is there a relationship among Arthur's brief return engagement with the military (presumably due to the declaration of war), his almost immediate relinquishing of his commission, and the fact that he soon goes roughly 7 years without penning a novel? Or is all of that merely coincidental? Were there simply so many fewer opportunities to publish a book during the war years that writers at the low end of the food chain like Mills would have had to do without? Or is it possible that something was seriously bothering him—perhaps mentally, physically, or both—that led to his prolonged dry spell?

I invite any of you who knew these times and can provide some context and insight to share your observations, experiences, and your opinions. It would certainly be greatly appreciated!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)