Thinking I'd sit down and fire off a short posting regarding yesterday's study of wills and probate, I find myself knee deep, once again, in information. Perhaps all of it is not George Mills-related, but some of it's quite interesting. At least to me. And other aspects of it are very pertinent to questions we've often asked here...

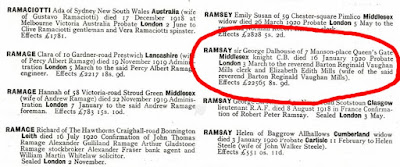

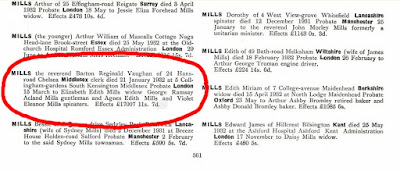

The probate record for the Revd. Barton Reginald Vaughan Mills contains this excerpt: "clerk died 21 January 1932 at 5 Collingham-gardens South Kensington Middlesex"

This was the first indication that we've had that, when Revd. Mills passed away "suddenly," he was not at home with his family at 24 Hans-road in Chelsea.

I thought, "Well, I'll go to Google Maps, take a virtual snapshot of 5 Collingham Gardens [above, left], and see if I can find out who he might've been visiting when he expired. I'll punch it up in a short post this morning and be done!"

The address 5, Collingham Gardens has an interesting history. The terraced freehold recently sold, on 29 January 2010, for £8,900,000 to Michaelis Boyd Associates of 108 Palace Gardens Terrace, London, who applied in December 2010 to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea for "the provision of rooflight on the second floor roof and alteration of 3 rear basement windows to french doors."

The address 5, Collingham Gardens has an interesting history. The terraced freehold recently sold, on 29 January 2010, for £8,900,000 to Michaelis Boyd Associates of 108 Palace Gardens Terrace, London, who applied in December 2010 to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea for "the provision of rooflight on the second floor roof and alteration of 3 rear basement windows to french doors."The building now houses Alphaco, a British waste-to-energy company, dealing in "Waste tires, Waste tyres, Scrap tyres, Scrap tires."

It also is the home of Collingham Gardens Child and Family Unit, an NHS psychiatric hospital for children and adolescents [right], apparently one of the few facilities providing inclusive "in-patient child psychiatric care for learning disabled children."

Here's a brief description of the 1883-1884 construction of 5 Collingham-gardens from 'The work of Ernest George and Peto in Harrington and Collingham Gardens', Survey of London: volume 42: Kensington Square to Earl's Court (1986), pp. 184-195:

"No. 5 is much the larger house [than No. 4], partly because of an extra low wing (which has now lost its stepped gable) to the north. Here too the plan and some features survive, showing that the levels were split, with the drawing-room this time at the back on the half-landing. The wooden residence by March 1886, was the fourth Earl of Wilton, who fitted one of the rooms up as an organ-saloon replete with model organ and patent hydraulic engines. The house and its fittings were reputed to have cost him upwards of £25,000."

"No. 5 is much the larger house [than No. 4], partly because of an extra low wing (which has now lost its stepped gable) to the north. Here too the plan and some features survive, showing that the levels were split, with the drawing-room this time at the back on the half-landing. The wooden residence by March 1886, was the fourth Earl of Wilton, who fitted one of the rooms up as an organ-saloon replete with model organ and patent hydraulic engines. The house and its fittings were reputed to have cost him upwards of £25,000."No. 4 could have been your residence at the time on these terms: "The price of a long lease here was £8,000, or it could be rented for £600 a year." No. 5 being "much" larger, can we assume the original price tag was "much" greater than those figures?

There are images of the interior, circa 1886-1888 and photographed by H. Bedford Lemere, to be found at: http://www.europeana.eu/portal/brief-doc.html?embedded=&start=1&view=table&query=5+collingham+gardens+brompton

By 1889, however, the Earl of Wilton no longer resided at 5 Collingham Gardens. On 22 March 1889, Mr. Robert Duncombe Shafto, a rich, former M.P. for North Durham died in his "London residence" at that address according to the Monthly chronicle of north country lore and legend, volume 3, 1889.

By 1902-1903, the address appears in the Royal Blue Book: Fashionable Directory and Parliamentary Guide as the residence of merchant banker John Conrad im Thurn, of J. C. im Thurn & Sons, merchants, 1, East India-avenue, EC.

By 1902-1903, the address appears in the Royal Blue Book: Fashionable Directory and Parliamentary Guide as the residence of merchant banker John Conrad im Thurn, of J. C. im Thurn & Sons, merchants, 1, East India-avenue, EC.And in 1938, Beryl Dallen (née Umney), wife of Deryck N. Dallen of Hartley Manor Farm, gave birth to a baby girl at 5 Collingham-gardens.

The above news, found in the 1938 periodical Chemist and druggist: The newsweekly for pharmacy, volume 128, indicates that perhaps the locale was no longer an upper-crust luxury abode at that time.

In fact, according to the website Lost Hospitals of London, 1947 would see the Metropolitan Ear Nose and Throat Hospital purchase "two freehold houses, 4-5 Collingham Gardens, SW5, which were converted to a 45-bedded hospital and Nurses Home."

But converted from what? The birth of baby girl Cherry V. Dallen at 5 Collingham Gardens in 1938 was probably not due to a visitor suddenly giving birth in the drawing room of a stately home. And that 1938 birth date is fairly close to the date of our interest: 21 January 1932, and why Revd. Barton R. V. Mills was at that address on that day when he suddenly died.

A clue to what became of 5 Collingham Gardens between being the residence of the moneyed J. C. im Thurn at the century's turn, and its sale to the Metropolitan Ear Nose and Throat Hospital in post-war 1947, was found in the strangest of places!

A clue to what became of 5 Collingham Gardens between being the residence of the moneyed J. C. im Thurn at the century's turn, and its sale to the Metropolitan Ear Nose and Throat Hospital in post-war 1947, was found in the strangest of places!In 2003's Niv: The Authorized Biography of David Niven by Graham Lord, we find this reference to Niven's mother on page 48: "In 1932 [Niven] was in Aldershot on a physical training course when Uncle Tommy telephoned to say that Etta was dying in a nursing home in South Kensington. He rushed up to London and was stunned to see how wasted she was by her cancer, but it was too late to say goodbye. Following an operation, peritonitis complications set in, she did not recognise him and she died on 12 November at 5 Collingham Gardens with her beloved husband at her bedside. She was only 52."

So, we know now that Barton Mills had been committed to a nursing home at 5 Collingham Gardens, about a mile southwest of his home at 24 Hans-road. Obviously not in the best of health, the death of Revd. Mills on 21 January of that very same year was apparently still unexpected.

Interestingly, on the heels of yesterday's examination of wills, probates, and bequests, there's also this snippet from Niven's biography: "She left an astonishingly large estate of £14 169 3s. 9d. net, the equivalent in modern terms of about $950,000 [obviously valued against the RPI]... three times as much as she had inherited from William Niven sixteen years previously. This huge increase in wealth was not caused by inflation, which was nil between 1916 and 1932, nor probably by clever investment, since the British stock market index fell fifty-five per cent between 1919 and 1931 as it was battered by the Great Depression. The only explanation is that Etta left her inheritance from William Niven untouched to grow for sixteen years in some high earning account... Niv's claims that she was desperately poor were quite untrue."

This additional bit of information is instructive for our purposes.

This additional bit of information is instructive for our purposes.Revd. and Mrs. Barton Mills inherited £22565 8s. 9d., from Edith Mills's father, Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, with whom they lived at the time of his death in 1920.

At the time of Barton's passing in 1932, his "effects" were valued at £17007 11s. 7d.—a greater legacy than that of Niven's mother, Lady Henriette "Etta" Comyn-Platt—but less than Sir George had previously bequeathed to them upon his passing in 1920.

Etta's legacy was worth "three times" its original value in 1916, meaning she had likely been left less than £5000. It's value had trebled by 1932 despite economic troubles in the intervening years.

The Mills family had taken almost £23000, and in four fewer years than Lady Comyn-Platt, diminished it to roughly £17000. And this does not take into consideration the residue of any 'effects' from the inheritance that Barton Mills had received upon the passing of his father, Arthur Mills, M.P., in 1898, which may have approached £10000. Afterwards, he spurned a secure living as vicar of Bude Haven, Cornwall and took the family and his career as a cleric to London. Mills then worked from 1901-1908 as an assistant chaplain at the Queen's Chapel at the Savoy, a position which probably paid little, but also would have helped them 'pay the bills' through the 20th century's first decade.

During that time in London, Mills also published a book of sermons, a book entitled Marks of the Church, and several works on the writings of St. Bernard that are still valuable resources to theologians today, as well as having served as a military chaplain during the First World War.

Figuring at least some small income from those ventures, it seems the Mills family was far from impoverished during the decades preceding Barton's death, as evidenced by the seven servants and governess listed in the household by enumerators of the 1911 UK census.

Figuring at least some small income from those ventures, it seems the Mills family was far from impoverished during the decades preceding Barton's death, as evidenced by the seven servants and governess listed in the household by enumerators of the 1911 UK census.In fact, it seems the Mills family pretty much lived a life of ease on money and 'effects' they'd inherited at various times, further evidence being provided by Barton's probate listing of his son as "George Ramsay Acland Mills, gentleman."

Other men listed among the names on the very same page of probate documents are described as "foreman," "baker," and "engine driver." There's no reason George wouldn't have been listed as a "schoolmaster" if he'd, indeed, been employed in 1932.

Apparently, Mills was at the very least 'between positions' as a schoolmaster at the time of his father's death, probably at home, being a gentleman and tapping out the manuscript for his first book, 1933's Meredith and Co.

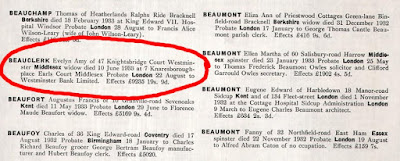

Thoughts on this have already been explored, and George's financial situation would have been augmented, along with that of his wife, Vera Louise, upon the death of his mother-in-law, Evelyn Amy Hart Beauclerk, in 1933. Although the executor of Beauclerk's will was Westminster Bank Ltd., it seems highly probable that some of her effects, totaling £9235 19s. 9.d, found their way down to her daughter, Vera, and son-in-law, George, gentleman.

Thoughts on this have already been explored, and George's financial situation would have been augmented, along with that of his wife, Vera Louise, upon the death of his mother-in-law, Evelyn Amy Hart Beauclerk, in 1933. Although the executor of Beauclerk's will was Westminster Bank Ltd., it seems highly probable that some of her effects, totaling £9235 19s. 9.d, found their way down to her daughter, Vera, and son-in-law, George, gentleman.Two things:

● Were George and Vera living with Evelyn Beauclerk or Barton Mills in 1932-1933? There are no telephone listings for the couple, so unless they were rooming with someone else or living in a hotel, they would have been secure with one London family or the other.

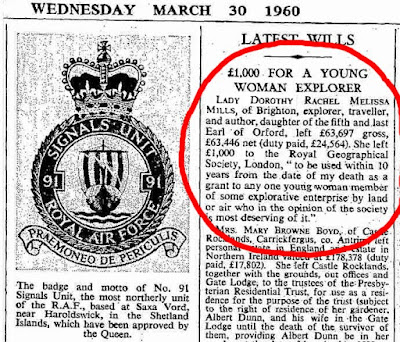

● And, given the firm financial footing the Mills family finds itself in, circa 1898-1920, why does the autobiography of Lady Dorothy Mills cry poverty during her courtship and marriage to Barton Mills's elder son, Capt. Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills of the D.C.L.I., George's half-brother by Barton's first marriage?

In 1914, Captain Mills is sent off to the war in France, but according to his autobiographical book, With My Regiment: From the Aisne to La Bassée [Lippincott: Philadelphia, 1916] written under the pseudonym "Platoon Commander", before departing he first "went up to London to my rooms to collect a few things."

In 1914, Captain Mills is sent off to the war in France, but according to his autobiographical book, With My Regiment: From the Aisne to La Bassée [Lippincott: Philadelphia, 1916] written under the pseudonym "Platoon Commander", before departing he first "went up to London to my rooms to collect a few things."His father lived in a 20-room abode at 12 Cranley Gardens, S.W., the likely location of those "rooms."

So Revd. Mills had room in his home for son Arthur, even if no money in his wallet for the newlywed couple after his nuptials to the above-mentioned and apparently disowned Dorothy Rachel Melissa Walpole in 1916. If Capt. Mills couldn't afford to support his wife on an infantry captain's wage, he certainly wasn't renting unlived-in "rooms" in London as well as a bed at a boarding at a house near his barracks on the Thames!

Of course, to believe that cry of poverty is to accept only the word of Lady Dorothy, who wrote her autobiography in 1929 after creating the persona of being a completely independent and modern woman, whose success was due in no part to the help of any man, be he father, lover, or husband. Her self-made, 'rags-to-riches' persona was as much what she was marketing as her stories, and if it appeared at all that she'd ever been well-cared-for as an adult by either husband Arthur or her in-laws, the Mills, it would certainly have taken much of the lustre off of her heroically feminist backstory.

Nevertheless, just one address in the probate record of Barton Mills has led to much additional knowledge of our George Mills—his career, his family, and his prospects, circa 1932. And the writing of this post turned out to be no 'quickie'!

As always, if you have anything that you can add, please don't hesitate to contact me—and thank you in advance!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)