By the end of September 1918

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke found himself demobilised from the military. The armistice would not be signed until 11 November of that year.

On 29 September 1918, the Kaiser had been advised that Germany's situation was hopeless.

General Erich Ludendorff,

according to Wikipedia, "could not guarantee that the front would hold for another 24 hours." Negotiations began in earnest in October.

To enlisted men around the camps in England, all of this must have been a secret, or just a part of an ever-grinding rumour mill at best.

Egerton Clarke, despite his weak heart and health issues, would have been anticipating staying in the service for a bit longer, and hitting the streets as a civilian during that month of October 1918 must have caught him a bit off guard, even if it was liberating. It's unlikely he had any knowledge that the hostile nations had entered into entente, and it's unlikely that he had been in the midst of preparing himself and planning for an armistice, and peace [above, left].

Egerton's 61 year old mother,

Emma Anna Clarke, was ensconced at Thorley Wash, Hertfordshire, with her widowed and wealthy elder sister,

Hannah Patten, so there was no immediate need to begin taking responsibility for her.

In fact, having been a scholar at

St Edmund's School in Canterbury up until joining the ranks, Clarke probably knew little, if anything, about caring for himself in the world outside of academia. What would he do? Where would he go?

When one knows nothing but school, it's likely one would attempt a return to the safety, order, and stability of an educational institution. That was the case with young Egerton.

During our study of

George Mills, Egerton's friend form the

Army Pay Corps, we learned of an opportunity presented to veterans of the war to attend university.

It was described here by

Anabel Peacock, an archivist at Oxford:

[A veteran] was exempted from taking Responsions (preliminary examinations for entry) and the examinations of the First Public Examination, under a decree of 9 March 1920. This decree stipulated that until the end of Trinity Term 1923 any member of the University who had been engaged in military service for twelve months or more before his matriculation, was permitted to offer himself for examination in any Final Honours School, despite not having met the statutory conditions for admission to that School. This was on condition that he had obtained permission from the Vice Chancellor and the proctors; that he had entered upon the third term and had not exceeded the twelfth term following his matriculation; and that he had paid the fee for admission to the examinations the decree excused him from.

This was the situation of which Mills had taken advantage when he matriculated from Christ Church, Oxford, on 19 October 1919, following his service under the Colours. It was probably under the auspices of the same decree that Clarke entered.

From

Nicola Hilton, Archives Assistant at Oxford, we learn this about Egerton:

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke was born on the 20 September 1899 in Canterbury, Kent. He was the second son of Percy Carmichael Clarke, Clerk in the Holy Orders, deceased. Before coming to Oxford, Egerton attended St Edmund's School, Canterbury, Kent. He matriculated (ie was admitted to the University) from Keble College on 14 October 1918. I cannot find any record of a degree being conferred (ie at a ceremony) on Mr Clarke.

[Note: Thanks to Janine La Forestier, Clarke's granddaughter, we can identify Egerton's brother: "In front of me now is a letter in which he is answering a question my mother must have asked concerning his brother. The letter dated December 1, 1942 refers to his brother as John (Jack) Percy Dalzell Clarke born in 1892 and died 21/02/1915." (08-17-11)]

Considering the above information, we once again find a connection between Egerton and George Mills. It may only be circumstantial, but with both gentlemen, formerly mates in the armed forces, matriculating during the same week—Egerton on Monday and George on Saturday—it seems strange to think that they had not been in contact and that they had not been sharing, at the very least, loose plans to further their educations at Oxford.

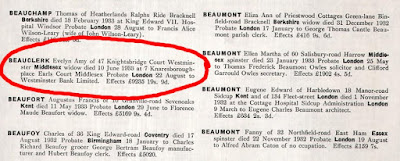

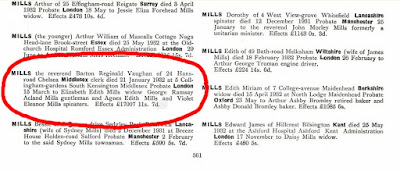

And it may not be far-fetched to believe that Oxford may have been George's idea—and if not his idea, then a very practical decision. His father, the

Revd Barton R. V. Mills, was a graduate, as had been his grandfather,

Arthur Mills, M.P., and Barton still was alive—he was serving as a "Chaplain to the Forces"—and able to take the boys, advise them, and show them around a bit. Egerton's father, the

Revd Percy Carmichael Clarke, had attended Cambridge, but unfortunately had passed away on 1902. There could have been no similar connection there.

It would have been comforting, one imagines, for both boys to know that they were heading off to university assured there would be at least one familiar and friendly face among the Oxon crowd.

By 1919, Egerton had become editor of

Clock Tower at Keble, presumably a literary magazine of some sort, and his name appears in the 1919 calendar. He, however, actually was busily working on another literary project—and a somewhat surprising one.

In 1920, Clarke would publish his first book, with this lengthy title:

The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier: Its History, Strains, Standard, Points, Breeding, Rearing, Management, Preparation for Show, and Sporting Attributes.

A new edition of this seemingly immortal book

is still in print today. The original 1920 first edition is described thusly:

By Egerton Clarke. With a foreword by The Rt. Hon. The Earl of Kenmare. Line drawings by Hay Hutchison. Illustrated. London: Popular Dogs Publishing Co. [1920]. 12mo., 78p., blue cloth with gilt lettering, and endpapers, illustrated with photographs and drawings.

This project may only be a surprise to those who aren't aware of George Mills and his family's great affinity for dogs. From

his father's early church-going days in Cornwall to reminiscences

from his last years in Budleigh Salterton, an overall fondness for dogs pervades his story. One could even make the argument that

a dog was the most popular character of a pair of his children's books.

Contrasting with the publication of

The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier, Clarke also published a book of poems entitled

Kezil and Other Poems [London : A.H. Stockwell, 1920]. Kezil is

available today as a scanned reproduction of the original text,

as well as on-line.

Clarke's dedication is quite interesting:

Dear ———

To whom one should dedicate a first book is often, I am told, a difficult question to decide.

For my part I can but feel that to offer this, my first to any one particular person would be both ungenerous and unfair, and it is for this reason I am persuaded to offer it, small though its value may be, to all those who have been good to me through-out my life.

So my offering is to you, friends, and among you :

Firstly, my Mother because you are also the mother of these poems ;

Nan, because without you these poems would not have been written by my hand, and because of your care for a stranger-child :

Madeleine, for the sake of your gentleness ;

Dorothy Sayers, in recognition of your kindness, and in appreciation of "Op" ;

Ernest Duggan, because of the door you opened for me ;

Gerald Crow, because you opened my eyes once and for all ; and last but not least

" Kezil," mysterious inspirer of so much.

EGERTON A. C. CLARKE.

THE GRANGE,

FOLKESTONE, June, 1920.

First of all, we find Egerton residing in Folkestone, near Dover, on the southeast coast, while writing at least this dedication.

We can determine some of his influences: Poet and biographer

Gerald Henry Crow (we hopefully will hear more about him soon) and Oxford's own

Dorothy L. Sayers, novelist, playwright, essayist, translator and poet. Here he specifically mentions the latter's interesting 1915 collection of poetry,

Op. I.

Ernest Duggan

Ernest Duggan and

Madeleine are two unknown characters in the life of Egerton Clarke, circa 1920. Duggan did not attend Oxford, and Egerton has left us no clues with which to determine his identity—there are more than a few Ernest Duggans in the Empire, circa 1920. And Madeleine will remain a mystery, at least until she gains a surname.

Nan, however, is essentially nameless, but quite interesting nonetheless. She is appreciated in this dedication

"because without you these poems would not have been written by my hand, and because of your care for a stranger-child."

These touching words imply not just the binding and careful treatment of a youth's injured hand, but that Egerton was treated with an overall care and tenderness that would not necessarily have been expected from a stranger. Heart-wrenching tales of orphans such as

Oliver Twist and

Jane Eyre were well-known, and while they had been around for many decades by the passing of Clarke's father in 1902, the more modern world at the turn of the 20th century still would not have been an orphan's proverbial oyster.

The presence of Nan caring for a

"stranger-child" also gives us insight into the lack of mothering suffered by Egerton during his youth. Where he experienced the tenderness of Nan's care is unknown at this point. Perhaps early in France she had been his nurse. Perhaps she was a matron at St Edmund's School in Canterbury who took a liking to the boy—or he to her. Perhaps she was simply someone who watched after him when school was out, someone who allowed him to leave St Edmunds occasionally.

Apparently, at whatever time Nan bestowed her kindness, Clarke had had no mother to provide it for him. Knowing that our best guess right now is that his mother was in the workhouse at Watford in 1911, that would go a long way toward explaining why Egerton so very much needed a

"Nan."

By contrast, Egerton's mother essentially is thanked for having given birth, and so, indirectly, having enabled him eventually to write the poems found within the text. There are certainly no immediate thanks for her, just an overall fondness, and a gratitude born of a worrisome life that finally seemed to have turned out well.

Missing from the dedication would be George Mills: A friend but not a powerful influence on Clarke's words and imagery.

"Kezil: A Fantasy" is a languidly alluring, Eastern erubescence of a poem, and well worth reading. Within the brief text, Clarke explains:

"'KEZIL' a Persian word meaning 'red,' or sometimes, I believe 'the red one.' — E.C."

But for our purposes here, I've selected a different poem from this volume to share:

IN HOSPITAL.

SEMI-CONSCIOUS.

PALE shadows round my head.

In whispering conference,

Nurses moved, and one said,

"B. one-seven-five ref'rence,

A. F. discharge," like ghosts,

They swayed unreal about

The room, The Red Cross hosts.

I wished someone would shout —

I wanted so to sleep.

A cruel "Hush !" "Be quiet."

Was all I heard and "creep

Like mice ;" and " Special diet."

Now and then a single word,

A phrase, against my brain,

Insistent beat and stirred

The quietude to pain,

Then somewhere slammed a door.

One moment echoed deep

Along the empty corridor,

Outside, I turned and heard no more,

And turned again and fell asleep.

Winchester,

Winchester,

1918.

When last time we read of Egerton's hospital stays in Winchester, it appeared to have been so easy for him: Resting in bed, recuperating, enjoying some time away from duty. In the poem above, written in that bed, we can see that clearly was not the case as Clarke, reconstructing his lack of lucidity, expresses the semi-consciousness of his condition and does his best to capture fleeting and fragmented scraps of his environment.

His volume ends tenderly with this poem:

FINIS.

To M. C.

NOT so much pity, what better an end

Than a night of shadow and quiet sleep,

When there's nothing of love that's left to spend,

Why should we linger to fidget and weep ?

O little's the pity of such a kind,

Let us light our candle and go upstairs

As children do, and dropping down the blind

A comfort make wherein to say our prayers ;

Not so tenderly now, no endless kiss,

Nor hold my hand so long, now love is pain,

But say "sleep well, sweet dreams," and things like this—

"Good-night," laugh too, lest Love find fault again,

Pity can go the way of love, and now,

As though we had nothing of that to mend,

Politely unkissed let us nod and bow,

With a "God bless you, dear," and "Good-night, friend."

Quite a contrast, I think, to

The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier (

"Teeth set right ensure a strong grip on the terrier's natural foe—vermin"). Perhaps these final verses are dedicated to Madeleine—M. C.—who was probably not his lover, ascending the figurative stairs with him 'as children do.'

Egerton Clarke would go on to write texts, poems, and a play. Here is as complete a bibliography as I can manage for his works after 1920:

•

The Ear-ring: A comedy in one-act. [London: Egerton, 1922]

•

The Death of Glass and Other Poems. [London: Egerton, 1923]

•

Nature Poems. [Amersharm: Morland, 1923]

•

The Death of England. [London: C. Palmer, 1930]

•

The Seven Niches: A Legend in Verse. [London: C. Palmer, 1931]

•

St Peter, the First Pope. [London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne, 1936]

•

Our Lady of Flowers. [London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne, 1937]

•

Alcazar and Other Poems. [London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne,1937]

Editions of

Who's Who in Literature in 1928 described Clarke in this way:

CLARKE, Egerton A. C. b. 1899. Ed. Clock Tower (KebleColl.,Oxford), 1919. Au. Of Kezil and Other Poems (Stockwell), 1920; The Earring (one-act comedy); (Hugh Egerton), 1922. Sub.-Ed. National Opinion, 1922. C. Morn. Post, West. Gaz., Colour, Even. News, Dy. Mirror, Poetry Rev., Oxford Poetry, Oxford Fort. Rev., Nat. Opinion. 73, EGERTON GARDENS. S.W.3.

So, by 1928 Clarke, who had published with a publisher called Egerton, was living in London, interestingly in Egerton Gardens, situated just across Brompton Road and less than 1,000 feet from the Holy Trinity Church in which George Mills wed

Vera Louise Beauclerk in 1925.

Egerton did not attend.

Clarke did follow George into the world of wedded bliss when he returned to Winchester and married

Teresa Kelly in the spring of 1926.

[Note: Janine also reports that "Therese received her nurses training from Guys Hopital in 1922." Note the spelling of Mrs. Clarke's name. A photograph depicting her nurse's uniform can be found at Rediscovering Egerton Clarke. (08-17-11)]

We can see from the bibliography and the brief biography above that 1926 was in the middle of a 6 year period during which Clarke did not publish a book, although another edition of

The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier would be published in 1927 or 1928.

An on-line

reference to this new edition describes it thusly:

Clarke, Egerton.

The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier

Popular Dogs Publishing Company, Ltd, c1928

65b, Long Achre, London, W.C.2.

Egerton Clarke of Narcunda Kennels wrote the “Popular Kerry Blue Terrier”, with a forward by the Rt. Hon. The Earl of Kenmare. Illustrations by Hay Hutchison. Published by Popular Dogs Publishing Company Ltd. in England in the 1920's. There is no publishing date in the book, but advertising for The Bog Kennels on page 71 makes reference to the dates 1925 and 1926. This is the first book published on Kerry Blue Terriers. Addresses breed history, Standard, Points, Breeding, Rearing, Management, Preparation for show, and Sporting attributes. A very scarce book. Hardcover, 78 pages.

All we really know of Egerton at this time is that, after his marriage, he is associated with a place called "Narcunda Kennels," presumably in England. By 1930, however, his wife crops up in the

Cruft's Dog Show Catalogue in the category [below, left]:

"Class 806—FOX TERRIERS—MINOR LIMIT BITCHES." It reads:

"2071 Mrs. England. Colonnade Credit. b. Born 24 Oct. 27. Breeder, Mrs. Egerton Clarke. By Earlington Goldfinder—Selecta Merit."

[Just an aside: In this 1930 catalogue, the first person listed in the

"Index to Exhibitors" is

"Abbey, Lady Ursula, Woldhurst manor, Crawley, Sussex. 770." Lady Ursula Abbey, a well-known breeder of show dogs, played croquet with and against George Mills and his sisters during the 1950s and 1960s.]

Clarke, if nothing else, obviously shared a love of dogs, and of breeding dogs, with his bride. It's an odd interest for a child, Egerton, ostensibly raised in an orphan school, to have picked up. One wonders what sort of life that "Nan" was able to share with him before he went off to war, or if the school itself had a Kerry Blue Terrier that became a love of Egerton's life.

In fact, could some of Egerton's dog tales (no pun intended) have made their way into the stories of George Mills?

Let's look at an excerpt from an even more informative biography of Egerton Clarke, this time from

The Catholic Who's Who & Yearbook: Volume 34, edited by

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand in 1941:

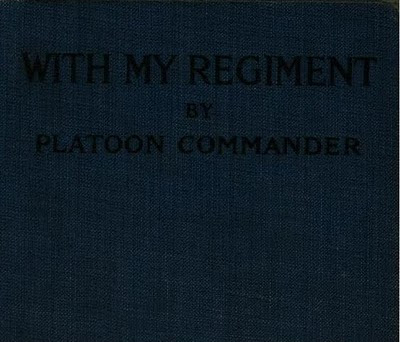

Clarke, Egerton — b. 1899, s. of Rev. Percy Carmichael Clarke, some time Anglican Chaplain of Dinard, Brittany; educ. St Edmund's Schl Canterbury and Keble Coll. Oxford; received into the Church 1922; served 5 Devon Regt 1917-8; a Vice-Presdt of the Catholic Poetry Soc.; Sec. St Hugh's Soc. for Cath. Boys of the Professional classes; m. (1926) Teresa, dau. of Joseph Wm Kelly and Clara Kelly (nee Sheil), of Dublin (2 sons, 1 dau.). Publications: The Death of Glass and Other Poems (1923) — The Ear-ring (1923) — The Popular Kerry Blue Terrier '(1927)— The Death of England and Other Poems (1930) — The Seven Niches: a Legend in Verse (1932)— Alcazar (1937).

By 1941 Egerton and Teresa Clarke had two sons and a daughter. But what's really interesting here, along with the title of the text [right], is that he was

"received into the Church 1922." During the mid- to late-1920s, Egerton had become involved in a new religion:

Roman Catholicism.

Dogs. The Army Pay Corps. Oxford. Writing. Neither staying at Oxford to earn a degree. Fathers who were Anglican clergymen.

And their own conversions to Catholicism.

Yes, there was a great deal that George Mills had in common with his friend, Egerton Clarke.

Next time we'll look at the children's books of Clarke and the final published text of George Mills, as well as reviewing Egerton's contributions to George's own literary work.

See you then…

Lady Acland, pictured, right, in a posthumous mezzotint executed by Samuel Cousins after an 1848 portrait by painter Joseph Severn, was buried in the graveyard of the Columbjohn Chapel at Broad Clyst, Devon, England.

Lady Acland, pictured, right, in a posthumous mezzotint executed by Samuel Cousins after an 1848 portrait by painter Joseph Severn, was buried in the graveyard of the Columbjohn Chapel at Broad Clyst, Devon, England.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)