Moving along to other matters, we come to Mr. Egerton Clarke. Clarke may be the most closely related person to George Mills we've examined for a while. Sometimes, this research can go far afield in an effort to provide context for the life of Mills, but in this case, the two men must have been friends, perhaps close friends.

In order to fully understand Egerton and relate him to Mills, we first have to examine his family of origin and that's what we'll be doing today.

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke was born in Canterbury, Kent, in 1899, the son of Percy Carmichael Clarke (1842 – 1902), then Chaplain in Dinard, Ille-et-Vilaine, Bretagne, France, who was the son of London stock broker John Jeffkins Clarke, who was born in Islington, and Fanny Jane Crossman, of Exmouth, Devon.

Percy Clarke was baptised on 12 January 1843, and the document lists his birth date as 4 May 1842 (Other records indicate his birth date was 22 May). His father's occupation is listed as "Gent."

The 1861 census lists Percy's parents' ages as John, 44, and Fanny, 40, in that year.

Percy attended Cambridge [above, left] and his entry in Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900 reads:

Percy Carmichael Clarke. College: TRINITY HALL Entered: Michs. 1860 More Information: Adm. pens. (age 18) at TRINITY HALL, July 26, 1860. S. of J. J. C., Esq. Matric. Michs. 1860. Ord. deacon, 1871; priest (Chichester) 1872; V. of Stapleford, Sussex, 1875-84. R. of St Michael-at-Plea, Norwich, 1886-95. Chaplain at Dinard, 1895-1902. Disappears from Crockford, 1903.

On 30 January 1868, at the age of 25, Percy married Sophia Austen, daughter of foreign merchant Henry Rains, at All Souls, Langham Place, Westminster. The marriage Bann [right] only lists Percy Carmichael Clarke as being "of full age," with his profession being "gentleman" residing in that parish in the county of Middlesex.

On 30 January 1868, at the age of 25, Percy married Sophia Austen, daughter of foreign merchant Henry Rains, at All Souls, Langham Place, Westminster. The marriage Bann [right] only lists Percy Carmichael Clarke as being "of full age," with his profession being "gentleman" residing in that parish in the county of Middlesex.The ceremony was witnessed by Sophia's father, her elder brother Rupert Rains, her elder half-sister Ann Sarah Rains, and Percy's brothers, Arthur Doveton Clarke and Egerton Harry John Clarke. Their signatures are all legible on the document.

Sophia Rains Austen Clarke was presumably a widow and older than Percy by 11 years. She appears on the 1871 census [below, left], living at home with her "foreign warehouserman" father, Henry, her mother, and her sisters. She was 38 at the time of that census, making 1833 her approximate birth year. She also was living with her daughter, Florence L. Austen, then aged 8 years.

Percy's new wife came with an instant family, and one of international pedigree. Sophia apparently was born in India, but there are no records to substantiate that. Little Florence was, indeed, born in Paddington, New South Wales, to her mother and her father, Benjamin Rupert Austen, gentleman, in 1863. Benjamin and Sophia had been married in London on 19 March 1861. Benjamin died in Paddington, NSW, in 1865, and Sophia had returned to England with their child.

Percy's new wife came with an instant family, and one of international pedigree. Sophia apparently was born in India, but there are no records to substantiate that. Little Florence was, indeed, born in Paddington, New South Wales, to her mother and her father, Benjamin Rupert Austen, gentleman, in 1863. Benjamin and Sophia had been married in London on 19 March 1861. Benjamin died in Paddington, NSW, in 1865, and Sophia had returned to England with their child.Newlywed Percy doesn't appear in the 1871 census (according to ancestry.com). Sophia and Florence were living with her father, Henry, in that year, during which Percy was ordained a deacon.

In 1881 [right], however, we do find him living with his wife, Sophia, and stepdaughter, Florence, at the Vicarage in Staplefield, Sussex, in the Parish of Cuckfield, where he was "Vicar of St. Marks Staplefield." They had no children of their own at this time.

In 1881 [right], however, we do find him living with his wife, Sophia, and stepdaughter, Florence, at the Vicarage in Staplefield, Sussex, in the Parish of Cuckfield, where he was "Vicar of St. Marks Staplefield." They had no children of their own at this time.Sophia Clarke passed away in Norwich, Norfolk, on 7 October 1887 at the age of 54.

Her will was probated on 21 December. The notice reads: "21 December. The Will of Sophia Clarke (Wife of Percy Carmichael Clarke, Clerk) formerly of Cliffdown-grange-road Eastbourne in the county of Sussex, but late of St. Michael –at-Plea Norwich in the County of Norfolk who died 7 October 1887 at the Rectory St. Michael-at-Plea was proved at the Principal Registry by Rubert [sic] Rains of 25 Sylvester–road Hackney in the County of Middlesex Manufacturer the Brother and the said reverend Percy Carmichael Clarke of St. Michael-at-Plea the Executors."

Sophia's personal estate was proved at £1,807 5s. 11d., and resworn in December 1888 at £2,688 15s. 7 d.

Now here's an oddity based on the above information:

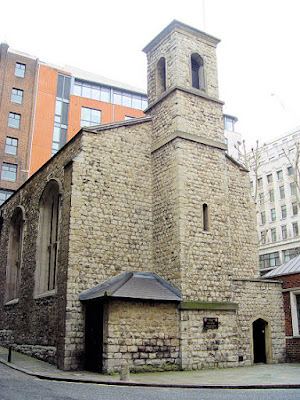

In 1887 or late in the spring (April-May-June) of 1888 (ancestry.com lists both years, but I only have seen the actual record for 1888), Clarke married Emma Anna Piper, daughter of farmer Francis Caton Piper and Hannah Parsey, who woked 130 acres at Hare Street Village, Royston, Hertfordshire (or Great Hormead, Hertfordshire in 1887). Clarke recently had moved to the living at St. Michael-at-Plea in Norwich, Norfolk [below, left] in 1886.

One way or the other, it didn't take Percy long to climb back into the marital saddle again, as they say.

One way or the other, it didn't take Percy long to climb back into the marital saddle again, as they say.Marriage records for Emma Piper cite the same pair of 1887 and 1888 dates for her nuptials. Given Sophia Clarke's death in October 1887, the 1888 date may seem more likely—but is it possible there was a quick ceremony late in 1887 that wasn't registered until 1888, or a wedding that was quickly annulled for being too soon after Sophia's death, with a ceremony then performed and consummated in 1888?

The only record of the birth of an "Emma Anna Piper" is in late 1856, and that was in Royston, Herts, where Percy and Emma were married in 1887 or 1888. She would have been about 31 years of age.

Either way, according to census records, 1891 would find 47-year-old Percy living with his young wife, Emma, 33, in Lowestoft, Sussex, along with their two-year-old daughter, Dorothy M. Clarke, and a nurse/domestic servant named Emily Mead. Little Dorothy Mary's place of birth is listed as Norfolk, Norwich, where she was born in spring of 1889. Percy's occupation is cited as "Clerk in Holy Order Rector at St. Michaels at Plea Norwich."

Percy would serve as rector at St Michael-at-Plea until 1895. Perhaps they were on a holiday there in Sussex at the time of the census, 5 April 1891.

After his time at Norwich, however, Percy would be named Chaplain of the église anglicane at Dinard, France, in 1895 [below, right].

Percy Carmichael Clarke passed away in 1902 in Dinard and a window was apparently dedicated to him. An inscription upon it reads:

The window is placed by the English and American colony of Dinard to The Glory of God and the affectionate remembrance of Percy Carmichael Clarke for 7 years the Chaplain who entered into his rest 13th April 1902. When I wake up after thy [sic] likeness I shall be satisfied with it.

I can find only one reference to Mrs. Emma Anna Clarke, that being in the year 2000, in the Bulletin et mémoires (Vol. 103) of the Société archéologique du département d'Ille-et-Vilaine. Unfortunately (for me), it is written in French:

I can find only one reference to Mrs. Emma Anna Clarke, that being in the year 2000, in the Bulletin et mémoires (Vol. 103) of the Société archéologique du département d'Ille-et-Vilaine. Unfortunately (for me), it is written in French:Portrait de Mme Clarke, qu'évoque Lawrence lorsqu'il se rend chez elle, villa Staplefield rue des Bains aujourd'hui rue Georges Clémenceau (la première villa à droite de la photographie).

Mme Clarke née Emma Anna Piper le 1 1 décembre 1857 à Beithingford, Angleterre, semble être une grande amie de la mère du jeune homme. Lawrence évoque cette dame en ces termes : "Je pars pour voir Mme Clarke et peut- être le frère Fabel» et encore «Je suis allé chez Mme Clarke et ai porté mon linge en lui donnant une liste» et enfin «Elle vous offre toute sa maison et

That is the entire fragment available to me. Using the Google's on-line translator, I found it roughly means:

Portrait of Mrs. Clarke, Lawrence evokes when he goes home, villa Staplefield now rue des Bains St. Georges Clemenceau (the first house on the right of the photograph).

Mrs. Clarke was born Emma Anna Piper 1 1 December 1857 to Beithingford, England, seems to be a great friend of the young man's mother. Lawrence refers to this lady in these words: "I'm going to see Mrs. Clarke and perhaps the brother Fabel" and even "I went to Mrs. Clarke and I wore my clothes by giving a list" and finally "It gives you all his house and...

My hunch is that the translation is none too perfect, so I will refrain from adding anything here. (Assistance from Francophones would be greatly appreciated!)

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke had been born in Canterbury, England, in July 1899 to Percy and Emma. His sister, Dorothy, would have been about 11 years old. His father would have been about 57 and his mother—quickly widowed when Egerton was just three years old—would have given birth to him when she was around 43. He also was baptized there on 18 October 1899 despite his father having been employed at Dinard [below, left, circa 1900].

Egerton was born to older parents and without a sibling close in age or of the same sex with whom to bond. His household obviously would have been a religious one, and at the point in Percy's life at which Egerton was born, it was likely to have been quite devout: Percy had taken his family abroad to France in search of a congregation at a time when many men may have been thinking about settling down into retirement.

Egerton was born to older parents and without a sibling close in age or of the same sex with whom to bond. His household obviously would have been a religious one, and at the point in Percy's life at which Egerton was born, it was likely to have been quite devout: Percy had taken his family abroad to France in search of a congregation at a time when many men may have been thinking about settling down into retirement.Of course, Percy had young children to support, so it may have been practical and economic decision. And, while there is no evidence, there may have been some scandal, or at least an irregularity, in Norwich, leading to Reverend Clarke becoming ensconced in Dinard. That would have been a very practical solution to such a problem: Get him out of England.

Remember that Clarke's tenure at St. Michael-at-Plea virtually began with the death of an aging wife and an almost immediate marriage to a very young one

No matter what, it was unlikely that Percy Carmichael Clarke took over as Chaplain in France as a promotion from St. Michael-at-Plea, or simply as part of some mid-life crisis. And we know the family, after all, never cut ties with England even a little—Egerton was born and baptised there, not in France.

Young Egerton does not appear on the 1901 UK census, likely because he was in France, the very young son of older parents, with no siblings, alone in a country in which everyone spoke a language different from the one used by his parents at home when they conversed, and with a congregation of transient vacationers on holiday, arriving for the mild climate... and the casino.

On top of all that, Egerton soon would be fatherless.

We don't know what happened to the family at that point, but an 11-year-old Egerton Clarke soon shows up in a summary for the 1911 UK census in an "institution" (presumably a school) in the village of Blean near Canterbury, Kent. The family still had ties to the area.

We don't know what happened to the family at that point, but an 11-year-old Egerton Clarke soon shows up in a summary for the 1911 UK census in an "institution" (presumably a school) in the village of Blean near Canterbury, Kent. The family still had ties to the area.Pictured, right, are children from the Blean School in 1910. 11-year-old Egerton is very likely one of the boys in the middle row, if this was, indeed, the "institution" he was attending in 1911. One hopes that Egerton had escaped the infamous workhouse there, but only greater access to the 1911 UK census would provide an answer..

[Note: It is actually unlikely that any of these children are Egerton; according to his family he did, indeed, attend St Edmund's School in Canterbury, Kent. (08-17-11)]

Let's fast forward, however, to the part of young Egerton's life during which he lost his mother. He was 31 years old when she passed away.

According to probate records, Egerton's mother, Emma Anna Clarke, would pass away on 24 October 1930. She had been living at 30 Portland-road, Bishops Stortford, Hertfordshire, but passed away at "Silverdale Sydenham Kent Administration (with Will)." Despite having at least one living child, the will was cited as "Limited" and probated on 23 January 1931 to George Ogilvy Jackson, solicitor attorney of Edward Arthur Baring-Gould,. Her effects were £194 12s [below, left].

This was not a rich woman. Percy Clarke may have left her a nice sum upon which to live—there are no probate records after his death—but we can see there was little left by 1930, if there ever was much. Even at that, it appears her legacy in 1931 went to solicitors, not family.

[Note: Boy, was I wrong! Solicitor Baring-Gould was married to Emma's daughter Dorothy, sister of Egerton Clarke. From Janine, Egerton's granddaughter: "Dorothy married a Baring Gould. He was referred to as Uncle Ted - so Edward Arthur Baring Gould - was one and the same." So, her probate was, indeed, handled by family. (08-17-11)]

It's likely that Egerton was raised by a mother who didn't have a great deal to spare. It’s possible his schooling may have been attended by his namesake uncle, Egerton Harry John Clarke, who had taken to the profession of young Egerton's grandfather, John Jeffkins Clarke: Stock Broker.

It's likely that Egerton was raised by a mother who didn't have a great deal to spare. It’s possible his schooling may have been attended by his namesake uncle, Egerton Harry John Clarke, who had taken to the profession of young Egerton's grandfather, John Jeffkins Clarke: Stock Broker.In retirement, when Uncle Egerton Harry John died in 1927, his probate left £18,525 17s. 3d. to his widow. We may need to look no further as to how young Egerton Arthur Crossman's education may have been funded, at least in part.

Next time we'll take a look at the results of that education, Egerton's time spent in the military during the First World War, and his relationship with George Mills.

Stay tuned…

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)