School is back in session here in Florida—stifling heat indices of well over 100°F be damned—and I've fallen behind in my correspondence.

This week I received news from Janine La Forestier, granddaughter of Egerton Clarke [pictured, right]. It was actually a note accompanying a forwarded message from, I believe, her cousin Camilla.

Here's Janine's note, followed by Camilla's correspondence, both which I have taken the liberty to adjust slightly for ease of readability here:

Morning Harry: I received [this] from one of [Uncle] Anthony's daughters. Very interesting about the paper—and that would explain a lot and be a much simpler explanation—so he was writing but [had] no way to get it published because of the shortages......I had heard of a shooting, but don't know any details.

Anyway - it might shed some light on why George didn't publish too—I guess we were looking for something a bit more interesting.

Take care and hope school is going well. They don't go back until September here—nice long holiday. Cheers, Janine

The following is from Camilla, on Wednesday, Aug 24, 2011 at 4:14 AM:

Dear Janine,

Where to start?

My father and the other two sent to boarding school long before the start of the war and not because of it. That was always the plan. By then money source was doubtful, although they always had nannies of whom my father formed a particular attachment to Nanny Toms.

Our grandparents were not untypical of the era and the old stiff British upper lip and sentimentality where children were concerned is not in evidence.

The children were sent [to school]. My dad [was] age 6 in 1935. His mother dropped [him] at the school and he remembers her driving off ([actually] being driven, of course). There was no tearful goodbye. Parents knew that contact at that time would be limited, and indeed it seems that the new nannies and houses added to the [children's] detachment from parents.

I think there is also a much more feasible answer as to why Egerton doesn't publish after 1939: There was no available paper. Rationing was everywhere and for everything. All printing would have been diverted for essential printing to do with the war effort. Poetry and literature would have been limited, and it is unlikely Egerton would have had the means [to publish his own work].

I think there is also a much more feasible answer as to why Egerton doesn't publish after 1939: There was no available paper. Rationing was everywhere and for everything. All printing would have been diverted for essential printing to do with the war effort. Poetry and literature would have been limited, and it is unlikely Egerton would have had the means [to publish his own work].

As to the funding for schooling, Egerton set up a charity for the funding of Catholic education for boys, my father being one of the few beneficiaries so [it was] a bit suspect.

Remember also he was a convert and had made a lot of notable contacts at university as was the vogue in those days. Catholic conversions were very 'of the moment,' as was the literary group he ran [which contained] some very notable names.

Aunty Dorothy wrote a very moving letter to my father in the 60's when he had inquired about [Egerton Clarke's] life. She told of a life for her and her brothers where they had a distant, unattached mother and not a happy childhood.

I have researched the Percy Carmichael [Clarke] and Emma Piper marriages, etc., and Angela has visited the church in Dinard, France, where there is indeed a window [dedicated] to [Percy Clarke's] memory.

Percy had an interesting life and was married before he married Egerton's mother. [He] worked for a bank, was sent to Australia for the bank, and was involved in the shooting of a man before he became a Church of England minister, but I think you might know all this.

Probably enough for now. Hope this gives a different view.

Fascinating! Thank you so much, Janine and Camilla!

We learn quite a bit from this missive beyond the most interesting aspect: Egerton Clarke's father apparently shot a man in Australia before becoming a vicar!

It seems that the distance between Egerton and his mother, Emma Anna [right], after the death of his father when Egerton was just three years old may have been, at least in part, because she was not a mother very involved with her children, and not because of financial hardship.

It seems that the distance between Egerton and his mother, Emma Anna [right], after the death of his father when Egerton was just three years old may have been, at least in part, because she was not a mother very involved with her children, and not because of financial hardship.

The nannies mentioned above, women who attended to Egerton's children, apparently mirrored the care given to him by nannies as a boy. We have seen that one nanny in particular was of such importance to him as to have been mentioned in the dedication of his first book of poetry.

In addition, we learn that Egerton may have missed his children during the Second World War, but that they were had not been separated from him by the hostilities, but by previously arranged design. It seems likely, however, that the war may have heightened his worry about them, or increased his desire to spend time with them, especially as he was becoming increasingly ill.

Regarding aspects of Camilla's message that would pertain to George Mills, a friend of Egerton's since their deployment in the Army Pay Corps at Winchester during the First World War, we learn that it was apparently somewhat fashionable at the time, at least among intellectuals, to convert to Roman Catholicism.

We know that when Edith Mills, George's mother, passed away in late 1945, services were held at Holy Trinity Church in Brompton, the locale of George's marriage in 1926. Despite the fact that George's father had been a convert to Catholicism since the 1880s, Rev. Barton R. V. Mills served as a Anglican vicar, chaplain, and cleric for his entire career.

We don't know if Edith Mills also had been a clandestine convert to Catholicism like her husband, Barton, but her 1945 funeral services were held under the auspices of the Church of England. The 1972 memorial service for George Mills much later, however, would be held at the Catholic Church of St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles, in Budleigh Salterton [left]. George obviously was not a convert because it was chic at mid-century, but one of deep faith and conviction.

We don't know if Edith Mills also had been a clandestine convert to Catholicism like her husband, Barton, but her 1945 funeral services were held under the auspices of the Church of England. The 1972 memorial service for George Mills much later, however, would be held at the Catholic Church of St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles, in Budleigh Salterton [left]. George obviously was not a convert because it was chic at mid-century, but one of deep faith and conviction.

Finally, we find that it is speculated that reason Egerton Clarke did not publish after 1937 or so may have been simple: The rationing of a limited supply of paper.

While I am certain that certainly would have played an important part in the difficulty poet Egerton Clarke and children's book author George Mills may have found in publishing during the war, it doesn't explain a few things.

First, we know that Egerton Clarke was disheartened about having at least one poem rejected, circa 1942. A shortage of paper may have caused him to be upset, but it does not explain why any bitterness would not have been felt during the entire war, but was encapsulated only in the rejection of a particular poetic submission.

Secondly, although Clarke succumbed to tuberculosis in 1944, George Mills never published another original work after 1939's Saint Thomas of Canterbury, through his death in 1972. Paper, at some point, did become available generally, and Mills saw his prep school trilogy of titles reprinted in the 1950s. Still, he never wrote again, save the odd letter to The Times.

Looking over publishing in the United Kingdom during WWII, we find that poetic volumes did continue to be printed. From 1940 through 1940, we find complete volumes of poetry published by Sir John Betjemen*, Cecil Day Lewis*, T.S. Eliot*, William Empson, Roy Fuller*, Robert Garioch, Rayner Hepenstall, Louis MacNiece*, Stephen Spender*, Dylan Thomas*, Henry Treece, W.B. Yeats and Rudyard Kipling (posthumously), Laurence Binyon*, Edmund Blunden*, G.S. Fraser, Alan Ross, A.L. Rowse, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Terence Tiller*, Vernon Watkins, Walter De la Mare*, W.S. Graham*, John Heath-Stubbs, J.F. Hendry*, Patrick Kavanaugh, Sidney Keyes*, Alun Lewis, Robert Nichols, Leslie Norris, John Pudney*, Henry Reed, Stevie Smith, Dorothy Wellesley, Kenneth Allott, Keith Douglas, Lawrence Durrell, David Gascoyne, Geoffrey Grigson, Michael Hamburger, Kathleen Raine, Keidrych Rhys, William Soutar*, George Barker, Alex Comfort, Patric Dickinson, Laurie Lee, John Lehmann, Mervyn Peake, Herbert Read, E.J. Scovell, and Charles Williams.

[Poets whose names are followed by an asterisk (*) published multiple volumes of poetry during those war years, having been allotted a great deal of that scarce paper!]

[Poets whose names are followed by an asterisk (*) published multiple volumes of poetry during those war years, having been allotted a great deal of that scarce paper!]

It's instructive to look at one young Irish poet of the era, W. R. "Bertie" Rodgers (1909 – 1969).

Rodgers [right] had attended Queen's University Belfast and showed promise as a writer. After graduating in 1935, however, he was ordained a Presbyterian minister and was appointed to the Loughgall Presbyterian Church in County Armagh, where he served through 1947.

In 1941, Rodgers published Awake! and Other Poems, which was critically acclaimed in both Britain and the United States, despite the fact that, according to Wikipedia, "the first edition was almost totally lost when the publisher’s warehouse was destroyed in the London Blitz."

Again, despite the destruction of his first edition, along with other texts in that warehouse, newcomer Rodgers was anointed with the publications of subsequent editions, despite the paper shortage. Rodgers soon eschewed his calling and became a script writer for the BBC after the war.

We find, sadly, that there was, indeed, paper enough to support the publication of a great deal of poetry during the Second World War, enough even to support the literary debut of a little known Irish cleric like Rodgers.

In the case of Egerton Clarke, there seem to be two possible conclusions as to why the available paper was not lavished upon his work.

First, he may not have been prolific enough. Perhaps, had he a portfolio of poems under his arm in 1942, his earlier lengthy string of critically well-received poetic texts may have caused a publisher to take him to press. Janine believes that it was Egerton's failure to have a single poem published that he "took very hard."

It's also possible that the critical acclaim that Egerton had earned had been somewhat forgotten. The poets publishing during the war, listed above, were not among his circle of literary friends, and it is possible that he had become "old news," having been relegated to the status of a minor poet during the years he spent during the 1930s writing children's books for Burns, Oates and Washbourne, a Catholic publishing house. He may have been consigned to the pigeonhole "Catholic poet," instead of simply being considered, as he once had been, an "up and coming poet."

It's also possible that the critical acclaim that Egerton had earned had been somewhat forgotten. The poets publishing during the war, listed above, were not among his circle of literary friends, and it is possible that he had become "old news," having been relegated to the status of a minor poet during the years he spent during the 1930s writing children's books for Burns, Oates and Washbourne, a Catholic publishing house. He may have been consigned to the pigeonhole "Catholic poet," instead of simply being considered, as he once had been, an "up and coming poet."

Let us not forget that, making things far worse, Egerton was in poor health during the war and would not live to hear of the fall of Berlin [left] or Tokyo.

George Mills was also in poor health during the war. He had returned to the Royal Army Pay Corps as an officer in 1940, but after a string of tragedies in his life, he relinquished his commission in 1943 due to "ill health."

While George's physician later in life, Dr. David Evans of Budleigh Salterton, claims that George was in good health at the end of his life and quite independent, something had overwhelmed him during the war, and George never wrote again.

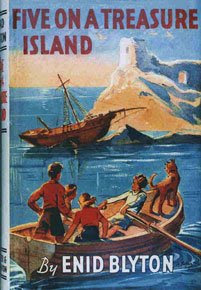

Trolling Wikipedia's lists of notable children's books, very few are from the era of the Second World War: Curious George (1941) by H.A. Rey; Five on a Treasure Island (1942) by Enid Blyton [left]; The Littlest Prince (1943) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry; and Pippi Longstocking (1945) by Astrid Lindgren.

Trolling Wikipedia's lists of notable children's books, very few are from the era of the Second World War: Curious George (1941) by H.A. Rey; Five on a Treasure Island (1942) by Enid Blyton [left]; The Littlest Prince (1943) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry; and Pippi Longstocking (1945) by Astrid Lindgren.

A contemporary British children's author Noel Streatfeild, for example, published only The House in Cornwall (1940) and Curtain Up (1944) [also published as Theater Shoes; pictured, right) for children during the war. Perhaps it was due to a shortage of paper—but she also managed to publish three novels for adult readers during the same years, 1940 – 1944.

Perhaps, then, it was only difficult to publish children's books in the U.K. during the war.

That also would seemingly be incorrect. Enid Blyton is listed as having published only one notable work [below, left] during WWII, but her entire published output between the years 1940 and 1944 was an incredible 88 books!

Clearly, there was enough paper to publish the works of major authors and poets, as well as minor works that would have been seen by publishers as a way to make some money (as in the case of the prolific Blyton) during the worldwide conflict.

Regarding George Mills, even if the recuperating author had been pitching book ideas to publishers during 1943, 1944, and 1945, it's likely that he was seen by then in the same way we see him today: A minor author with limited earning potential for a publishing house.

Regarding George Mills, even if the recuperating author had been pitching book ideas to publishers during 1943, 1944, and 1945, it's likely that he was seen by then in the same way we see him today: A minor author with limited earning potential for a publishing house.

In the cases of both Egerton Clarke and George Mills, the lustre that once had been found on their careers a decade earlier had diminished dramatically, and pages they once might have published were being given instead either to dependable and established authors, or to new writers who might be potential literary stars.

It is easy to see why Egerton and George would have taken the subsequent downturn in their careers poorly, and perhaps bitterly.

Thank you once again, Janine and Camilla, for helping to fill in some of the gaps in this research. It is very much appreciated.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)