Much of our story here involving George Mills has revolved to a great degree around one thing lately: Religion. However, there certainly are many threads running through his story, and in this—oddly my 300th and hopefully not my final post— we'll begin to summarize, to some degree, what we have learned about George's life.

The Mills Family and Catholicism

It seems odd, at least to an American viewing it from the vantage point of the 20th century, that George's father, the Revd Barton R. V. Mills, converted to Roman Catholicism while attending Oxford around 1883 and then took a series of positions as an Anglican vicar afterwards, eventually ending up as assistant chaplain at the Chapel Royal of the Savoy in London, and doing a segment of Queen Victoria's funeral service. No one else seems surprised or very much cares save one man: The current chaplain of the Savoy, Peter Galloway, who simply chooses to disbelieve, preferring the strange point of view that the public record of the conversion of Mills must be in error.

I guess that's why they call it "faith."

In fact, I recently wrote to a Church of England vicar of today to ask about the relations among the Anglican Church, the High Church, the Low Church, Anglo-Catholicism, and Roman Catholicism. I let him know that some very learned people in the U.K. have expressed directly to me that there's really not much difference at all, especially today, and that it's unlikely anyone cared very much back then, either—hence the vicarages and the chaplaincy to the Savoy being awarded to Mills.

Like most people I've contacted who are involved with the Church, that vicar never bothered to reply to a collegial request for research assistance from an educator. (Just an aside: When clerics contact scholars, do they expect assistance in their own research? If so, that would be quite hypocritical!)

Like most people I've contacted who are involved with the Church, that vicar never bothered to reply to a collegial request for research assistance from an educator. (Just an aside: When clerics contact scholars, do they expect assistance in their own research? If so, that would be quite hypocritical!)In lieu of that learned opinion, the difference between the Anglican Church and Roman Catholicism seems, however, to have been a big enough deal for some people actually to make the effort to convert from the Church of England to Roman Catholicism, and to form specific religious societies, and publishing houses, and the like, especially when converting was 'of the moment' in the early 20th century.

I think it might a bigger surprise that George Mills was friendly with Roman Catholic converts, frequenting their haunts, publishing with their publishers, and basically living a very Roman Catholic life, all the way through to his funeral service at the Catholic Church of St. Peter's in Budleigh Salterton (as opposed to the St. Peter's C of E there), than it is that he might've been gay, for example, as we recently heard discussed.

Given the overtly Catholic nature of many of George's friends, religion seems to have been the windmill at which Mills tilted most as the son of an Anglican vicar—even if his father also had been a closet Roman Catholic—in an extended family involved fully in Church of England. His sexuality would seem to have been secondary.

Having moved away from the Church of England also seems to be an explanation why distant relatives living today simply don't know the "Barton R. V. Mills" twig on their branch of the family tree exists, let alone anything about any of the Mills family. Honestly, except for a few recollections by a few ancient relatives of George's Uncle Dudley Acland Mills, now living in Canada who do know, but apparently are not interested in the Mills family at all!

A Childless and Forgotten Family

It didn't help that all four of the Rev. Barton Mills's children died childless (unless George's brother, Arthur, had late-in-life offspring I can't locate), but there's something more to the fact that virtually no one knows or cares who these people are or that they even existed.

Except, to some degree, for the women who married into the Mills family.

In the case of Vera Beauclerk (Mrs. George Mills), her family today bviously knows about her, and she's easy to trace—being descended from William the Conqueror.

Considering Edith Ramsay (Mrs. Barton Mills, George's mother), her surviving family today knows of her, but not very much, even to the point of having documented her Christian name incorrectly [as Elizabeth]. It's as if she dropped off the very face of the Earth when she left her nuclear family after marrying Barton Mills and moving to Kensington, just blocks from Buckingham Palace. Of Edith's parents, much is known today, including the possession of a great deal of ephemera, much of which has appeared among these pages. Of Edith herself: Nothing, save the image of her as a toddler in the montage at left.

Considering Edith Ramsay (Mrs. Barton Mills, George's mother), her surviving family today knows of her, but not very much, even to the point of having documented her Christian name incorrectly [as Elizabeth]. It's as if she dropped off the very face of the Earth when she left her nuclear family after marrying Barton Mills and moving to Kensington, just blocks from Buckingham Palace. Of Edith's parents, much is known today, including the possession of a great deal of ephemera, much of which has appeared among these pages. Of Edith herself: Nothing, save the image of her as a toddler in the montage at left. The last in-law, Lady Dorothy Mills (née Walpole, Arthur's first wife), maintained a high profile of her own as an author/explorer until a horrific car accident drove her into retirement, despite the fact that her family quite literally disowned her for marrying a soldier. They divorced in 1933. Also childless, she has been allowed to fade into obscurity since her death in 1959.

Her onetime husband, George's half-brother Arthur, apparently barely acknowledged his family, and is the best-kept secret of all the Mills siblings.

Something is amiss in all of that.

George, Arthur, and their spinster sisters—Agnes and Violet; very athletic girls, into the Girl Guides and scouting, who never found mates at all and were devoted to George, and he them—were an entire little family all of whom, sadly, had failed to reproduce to continue the family name.

Still: Why does almost no one recall that these people ever were?

George Mills at School

George had been in a great deal of pain in his life and not all of it could have been addressed with an aspirin or two. Physically slight of build, with varicose veins as a boy, and saddled with a speech impediment [possibly a lisp like his sister Aggie's, causing an unclear voice], I can see why he would've preferred sensitivity in the people around him—but boys at school probably tormented him. He basically washed out as a young scholar, spending a brief two years at Harrow. He would not have excelled at something he always loved: Sport, especially cricket. Stronger, more confident, less sensitive boys would have made his life miserable in a variety of ways, even unknowingly.

George had stockpiled many regrets based on his own preparatory schooling.

George Mills during World War I

I don't see Mills's life having been much better as a "Grade III" army recruit (unfit for most military duties) in the service during the First World War. Except for his time in the Army Pay Corps, the corps where the friend and fellow B-III, Egerton Clarke, was also assigned, the slightly built and sensitive Mills must have faced similar torments to those he'd known at school.

The army was another place where Mills would have been a failure: He was a washout as a soldier, a washout as a APC clerk, and a fellow who had been determined fit only to be a "fatigue man"—the lowest form of military life, with virtually no hope of promotion. And things, as we've seen, got worse for him after his friend Egerton was hospitalized and demobilised, leaving George in Winchester alone.

George Mills at Oxford

George Mills at OxfordAfter having been demobilised himself, George attended Oxford for three years or so and managed to leave without having taken a degree or a single examination to earn one. The academic and social discipline required by an institution like Oxon would have been a struggle for Mills, who had lived a sheltered life, especially in regard to having been allowed to 'quit' when the going got tough, as they say, during his preparatory schooling.

Without that degree, gaining a career in which he could have been a success—and make his father (twice an Oxford graduate) proud—would prove then to be difficult.

George Mills As a Non-Author

As a youth grown into a man, George Mills had been the only male member of his immediate family who had not published a book, from his paternal grandfather on down! While that may never had been said to him directly, when the men all were discussing their books and their publishers, George had to know he was the only one just listening.

George Mills, Schoolmaster, 1926 – 1933

Failed as a schoolboy and scholar and failed in the military, by 1933 we know George also failed to hold down a regular teaching job for very long. He had moved from school to school as a teacher between 1924 and 1933 (one assignment being as far afield as Switzerland) in search of a situation. This presumably meant time spent away from his family, and even his wife.

Something during this time, however, 'clicked' for Mills.

It seems to have been spurred by his relationship with Joshua Goodland at Warren Hill School in Meads, Eastbourne [below, left]. Although Goodland had managed to take two degrees during his seven years at Cambridge, he never fully settled into a career. Goodland was an occupational nomad, veering from a career in teaching to becoming an architect, and following that, a career in law. He then returned to teaching and became Head Master at Warren Hill before eventually turning to his final vocation, serving as a vicar in the Church of England.

Goodland was a diminutive but passionate man, older than George, who had traveled around the world and possessed a myriad of skills and talents, but who lacked a sort of stick-to-it-ness (as we say in the States) that would have inspired the erratic young Mills to find success in his own life in a similar way: Not necessarily along a single, direct career path, but divergently.

Goodland was a diminutive but passionate man, older than George, who had traveled around the world and possessed a myriad of skills and talents, but who lacked a sort of stick-to-it-ness (as we say in the States) that would have inspired the erratic young Mills to find success in his own life in a similar way: Not necessarily along a single, direct career path, but divergently.In 1932, Barton Mills, George's father, passed away. This simultaneous event, a tragedy, also seems to have been a catalyst and clearly a pivotal point in George's life.

Vindication of His Failures

Mills tackled his lifelong failure issues seemingly one at a time, and began to assemble a future. Whether or not this was consciously done, we cannot tell.

He seems to have gained a great deal from his time spent at Oxford, even if he didn't earn a degree. He met and had been exposed to a sensitive class of fellows who, rather than hurting George, seem to have understood him—perhaps that was something he'd never experienced within his own family—and those well-educated men even liked and cared about him. He learned about himself as a person, as well as receiving reinforcement regarding his faith in Catholicism.

His university experience planted many seeds that would later begin to flourish.

George Mills Returns to Prep School

Some success and popularity at Oxford led Mills to do something that many children-grown-into-teachers do: Return to the scene of previous educational 'crimes' against him and others like him, intent on 'righting' many wrongs that had been perpetrated upon him while at school.

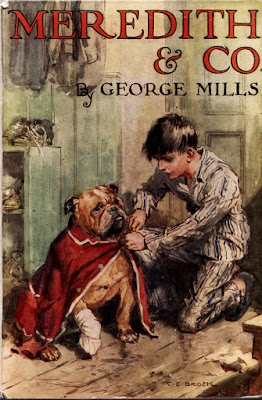

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, under the auspices of progress and enlightenment in education, he then spent time teaching in schools and being the sort of schoolmaster he'd wanted to have, I suppose: His first book is fully titled Meredith and Co.: The Story of a Modern Preparatory School.

Key word: Modern. Things now were finally different in the world of British education, and George had returned to become a part of it all.

Much of what he wanted as a schoolmaster likely was acceptance within some educational institution more than any sort of abstract revenge: During his time in the classroom he was liked and appreciated by faculty, staff, and students, all within a milieu in which he was once considered a failure.

George Mills Finds Success as an Author

George Mills Finds Success as an AuthorAfter he was unable to hold onto one job for long as the world moved into a severe global economic depression, George then wrote books about his fledgling teaching career—a vocation that he may not have returned to, as far as we know. (There's no evidence he taught more than a single term after WW2.)

This process of writing and being published, in a family of both distinguished scholars and popular authors, enabled him to raise his esteem, I'm sure, in the eyes of his family, as well as in his own. We find that yet another area in which he was dismal failure could be checked off his metaphorical list, and not just barely: His books became popular and were unique in having captured much of the behavior, slang, and idiom of British Schoolboys between the wars, becoming the forerunners of a literary genre that would later flourish.

Once Mills published his third and fourth book in 1939, the label "author" could clearly and permanently be attached to him. Clouds were gathering darkly over a Europe increasingly held in the steely embrace of fascism, however.

George Mills and the Royal Army Pay Corps

There were not many failures left to vindicate, but next came George's lack of any sort of success in the military in general, and within the Army Pay Corps in particular. George had been summarily and permanently sent packing from the APC during his dismal service there during the Great War, so I understand why, while enjoying success as a writer at 43 years of age, all of that was cast suddenly aside. He obviously had put his name into the Officer's Reserve pool as a War Substitute (probably claiming to have the Oxon degree he'd falsely told his prep schools that he had earned) at the onset of the Second World War.

We find that Mills soon ended up back in the Royal Army Pay Corps in 1940, and it must have been all the sweeter when he walked in this time wearing the uniform of a 2nd Lieutenant. George then would have been walking on metaphorical air when he eventually was promoted to full Lieutenant in 1942! Check 'success' in that area off of his 'vindication list'—although it would be short-lived.

Never what we'd call a "finisher," Mills relinquished his commission as an officer in 1943, after just two years, due to "ill-health." He was awarded the honorary rank of Lieutenant.

Never what we'd call a "finisher," Mills relinquished his commission as an officer in 1943, after just two years, due to "ill-health." He was awarded the honorary rank of Lieutenant.George's life had been bombarded by loss during this time period, and he would suffer more by the end of the war—the deaths of friends (Terence Hadow, Egerton Clarke), colleagues (Capt. Wm. Mocatta, Joshua Goodland), and loved ones (his wife, Vera, and his mother, Edith), all between 1939 and 1945—which is something he admittedly had in common with the rest of the British Empire during that time frame. It is distinctly possible Mills then suffered from terrible depression.

As we know, George's "ill health" didn't permanently debilitate him, which is fortunate because George had one more item to be dealt with on his 'checklist' of youthful failures, and it would be the one that took the longest time for him to get around to vindicating.

George Mills and Sport

Where Mills was and what he was doing between the end of the war and the late 1950s is unknown: They are George's Missing Years.

By the late 1950s, however, he was playing competitive croquet out of Budleigh Salterton and had quickly and respectably shaved down his beginner's handicap. George went on to win a number of tournaments along the south coast of England before he played his last match in 1970 at 76 years of age.

It's unlikely that athletic competition was something the slight Mills had ever felt good about before the age of 60, and though I imagine his trophies could not have been described as huge, I believe they must have been treasured by him as if they had been colossal!

George Mills and Catholicism

In a world that so recently had been fought over quite violently by Fascists and Communists, there is circumstantial evidence that Mills may have had Socialist leanings during the time. Toss in the lifelong struggles George had had along the way with religion, discussed above, and Mills always seemed to have had something on his philosophical plate!

Mills attended the local Catholic church in Budleigh, where he lived his last years with his spinster sisters, Agnes and Violet, at Grey Friars on Westfield Road, next to the croquet club. With his allegedly Anglican father no longer living, and with no close relatives nearby to embarrass (Arthur had died in New Forest in 1955), he finally could be comfortable and public worshipping in his chosen faith.

One does wonder about his relationship with croquet's Maurice Reckitt, the renowned Christian socialist author who, however, was "terribly anti-Roman Catholic," according to fellow player, Dr. William Ormerod. Did they ever speak of it?

The Social George Mills

From the time of George's first teaching appointment at Windlesham House School in 1926, to his obituary written in 1973 by Lt.-Col. G. E. Cave for the Croquet Gazette, George Mills was seen as a very social man. He has been described as "sociable," exuberant," "lovable," and that "He made people laugh, a lot."

From the time of George's first teaching appointment at Windlesham House School in 1926, to his obituary written in 1973 by Lt.-Col. G. E. Cave for the Croquet Gazette, George Mills was seen as a very social man. He has been described as "sociable," exuberant," "lovable," and that "He made people laugh, a lot."He once was also so keen on children, and was so able to become part of their world in his prep schools that he could write unprecedented and insightful books about the world of his students, books that looked far beneath the veneer of the prep school classes, curricula, and discipline and saw the inner child.

One wonders, then, why so very few people remember George.

His physician in Budleigh does, but except for a few patent comments, Dr. Evans of Budleigh isn't saying much.

Barry McAleenan, a great friend of this site, knew of Mills as a child, but only really recalled that he likely was a user of snuff. (Barry, by the way, possesses the best photograph of George Mills known publicly, and it is seen at the top of this page.)

Joanna Healing and Judy Perry remember many of the characters during that era of croquet, and while Agnes and Violet Mills are more easily recollected (especially Agnes), George Mills really is not. Not at all.

A clue arrived recently via Martin Granger-Brown, who recalled George's sister "Aggie was very haughty and posh and used to look down on people," something that could have affected public perception of George as he chose to live the final years of his life in her company.

Another clue may be found in the recollections of Dr. William Ormerod. Upon hearing George described as "exuberant," "loveable," and "enthusiastic," he replied, "Those are words I would use to describe Gerald Cave himself."

Given the speech impediment of Mills, Mills may have been extremely uncomfortable with strangers. He may also have been somewhat of a chameleon, reflecting the positive qualities of those he was with, so as to keep himself in harmony with situations that could have caused him a geat deal of social anxiety.

Perhaps Mills was "exuberant," "loveable," and "enthusiastic" with those who, themselves, acted exuberantly, lovingly, and enthusiastically with him. And it follows that those who were cold or unaware of him always would remain so, as he likely would have called no attention to himself.

This would also explain why so many were unaware, during the final years of Mills's life, of his past success as an author.

Summary

Why is a man—George Mills—who was known to be so sociable, so amusing, so full of life and laughter, and a man who not only enjoyed children but seemingly understood them as well, remembered by so very few?

The life of George Mills seems to have been divided in to two halves: Failure and Success—or at least noteworthy degrees of each.

It took fifty years, but George finally vindicated himself regarding the aspects of his life in which he felt like a failure.

It doesn't appear that he ever struggled to survive financially, and that he was a relatively popular, stylish gentleman through the end. He left us childless, as did his siblings, so there are no stories of Uncle or Grandfather George at Christmas, Baptisms, funerals, or on holidays. No stories told by him were repeated to a subsequent generations of children. No one remains, then, to recall the way he spoke, smoked, or laughed.

He ended a man about whom, following his death, very few would ever think again.

The following quote recently entered my e-mail box as part of the signature of a sender, and it immediately struck me:

To laugh often and much; to win the respect of intelligent people and the affection of children; to earn the appreciation of honest critics and endure the betrayal of false friends; to appreciate beauty, to find the best in others; to leave the world a little better; whether by a healthy child, a garden patch or a redeemed social condition; to know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is the meaning of success.

———————————————————————————————————————————————Ralph Waldo Emerson

Those are hopeful words by which we any of us might assess the true value of our lives.

Those are hopeful words by which we any of us might assess the true value of our lives.Emerson's words summarize the impact that George Mills—now seemingly forgotten—had on the world. Whether or not he is remembered widely doesn't lessen any of the impact he did, indeed, have—especially on me.

Still, it's nice for someone, anyone, to be remembered, and that's what Who Is George Mills? has always been about.

Unless new information comes to light (as, I'm grateful to say, so often has happened here over the past year or more), unless I'm contacted by a relative, friend, or acquaintance who remembers George and his family, unless we receive a copy (or scan, or photocopy) of his last children's book, or unless we discover his letters or other ephemera that would help us know more in answer to the question, "Who Is George Mills?" then my work here is essentially done.

And I've enjoyed it all. Thank you so much: Everyone.

Goodbye for now, George.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)