Hello, everyone! My, it's wonderful to have something to write about George Mills again—even if it won't be about George directly!

I'm delighted! And when it rains, it tends to pour—well, at least here in sub-tropical Florida—and I awakened this morning to find not one, but two Mills-related items in my mailbox. The first regards the home of George's widowed mother, Edith, and spinster sisters, Agnes and Violet, during the Great Depression, when the Mills women lived at 21 Cadogan Gardens, S.W. [left].

During that time, and during the Second World War, a boarder at the home, specifically in "21B," was Lady Frances Ryder. In a previous post we discovered that she did, indeed, live with the Mills during the war, and facilitated the Isles Dominion Hospitality Scheme from her flat with the help of Miss Celia Macdonald.

Reader Roger Kelly writes:

In Who Is George Mills I see you are -like me- puzzled by Lady Ryder and what went on at Cadogan Gardens. It was a club, and used as a postal address and meeting place for people of no fixed address. Close to the heart of the British establishment, there were filing clerks behind the scenes: think of the first ten minutes of "A Matter of Life and Death" -"Stairway to Heaven" to you.

In Who Is George Mills I see you are -like me- puzzled by Lady Ryder and what went on at Cadogan Gardens. It was a club, and used as a postal address and meeting place for people of no fixed address. Close to the heart of the British establishment, there were filing clerks behind the scenes: think of the first ten minutes of "A Matter of Life and Death" -"Stairway to Heaven" to you.Lady Ryder's organisation comes up in an online biography I'm writing of an overseas student [Jack Mitchell, right] in England towards the end of 1935.

See it on my website here

www.kosmoid.net/technology/jackmitchell

best wishes

Roger

near Edinburgh

Thank you so much, Roger!

While the Mills women are not mentioned on that web page, we find there must have been quite a bit going on. The hospitality scheme is clarified here at the well-researched website:

Social efforts to engage new Rhodes scholars continued to target Winston. Jack also would be drawn into the net by the end of the year. It started with an invitation to meet Miss Macdonald of the Isles at Rhodes House on Friday 1st. It was an informal dance evening making things go with a swing and about 30 Rhodes Scholars were there of all nationalities –a high proportion Americans - with a good number of quite nice English and Danish girls. Miss Macdonald of the Isles, whose very name helped to cast a spell, announced that a social week was being arranged in London for Rhodes Scholars and others in the second week of December, and there would be a chance to stay with different people in the Christmas break too. Very kind, but as Jack says, these people arrange the “scheme” in much the same way as others as well-to-do go “slumming”.

Miss Macdonald ran Lady Ryder’s Empire hospitality scheme for English-speaking officers, Rhodes scholars and other eligible students from the dominions and overseas. At the scheme’s headquarters in 21B Cadogan Gardens, Sloane Square, London, tea was dispensed and dances were held. Card indexes were kept of 1600 or so potentially lonely visitors who might be helped each year, and of appropriate households prepared to provide a home, friendship and the prospect of some suitable female company for weekends, vacations, leave, study and convalescence. Girls of good family could be drafted to serve as live-in help for host households while the young overseas guests came to stay. It all seemed very well organised. The recipients were duly grateful if sometimes a little amused by all the thoughtfulness for their moral and physical welfare. In the war years ahead Miss Macdonald’s pastoral work would be extended to Czechoslovak, Polish, Norwegian, Dutch and French free forces officers and to the airmen who would find themselves stationed in the hundreds of airfields scattered around the country.

Miss Macdonald ran Lady Ryder’s Empire hospitality scheme for English-speaking officers, Rhodes scholars and other eligible students from the dominions and overseas. At the scheme’s headquarters in 21B Cadogan Gardens, Sloane Square, London, tea was dispensed and dances were held. Card indexes were kept of 1600 or so potentially lonely visitors who might be helped each year, and of appropriate households prepared to provide a home, friendship and the prospect of some suitable female company for weekends, vacations, leave, study and convalescence. Girls of good family could be drafted to serve as live-in help for host households while the young overseas guests came to stay. It all seemed very well organised. The recipients were duly grateful if sometimes a little amused by all the thoughtfulness for their moral and physical welfare. In the war years ahead Miss Macdonald’s pastoral work would be extended to Czechoslovak, Polish, Norwegian, Dutch and French free forces officers and to the airmen who would find themselves stationed in the hundreds of airfields scattered around the country.Later in this wonderfully thorough biography, we find:

Saturday evening [7 December 1935] was set for Miss Macdonald’s big At Home at 21B Cadogan Gardens. Among the throng with Winston –and missing Jack– were Eric Haslam, his friend Hoon of Victoria, Gibson a friend of Wood, Porus, Rossiter of Merton, Norman Davis again, Lionel Cooper of Capetown, McPherson, Stewart of Canada, and more ad infinitum. Among the girls were Miss Lovegrove of Canada and Miss Dinah Nathan of Wellington NZ.

The Lady Ryder Scheme’s hospitality continued through the week with a Sunday trip to Hampton Court Palace, a personal tour of Sir Christopher. Wren’s Old Court House [right] and afternoon tea with its owner Norman E. Lamplugh, dinner with the Holding family in Kensington, on Monday a coach tour from Cadogan Gardens to be shown round the vast HMV record factory at Hayes, then to hosts Mr and Mrs Powell in Earls Court with Gunther Motz, Miss Hearn from Canada and Miss Lewis from Australia. Afterwards all were invited to a magnificent Ball given by the Goldmiths Company where Winston spent time with Motz, Miss Johnson from England and Miss de Charme from Paris. Tuesday took them to Twickenham for the varsity rugby match where Oxford’s kiwi captain Malcolm Cooper excelled against Cambridge; in the evening to a studio performance at the Gate Theatre by Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies. Wednesday was set for lunch in Kensington with the family of Sir John Gilmour the recent Home Secretary and dinner in the City with the Grocers Company where the speakers were Jack’s old friend Lord Bledisloe and Miss Macdonald of the Isles. Thursday’s trip from Cadogan Gardens was to Hatfield House with a personal tour conducted by the tough old Marchioness of Salisbury. On Friday the academic aspirants were dispersed to their hosts in the country for the weekend. And Jack could join in for a break at last after his busy week in the Lab.

The Lady Ryder Scheme’s hospitality continued through the week with a Sunday trip to Hampton Court Palace, a personal tour of Sir Christopher. Wren’s Old Court House [right] and afternoon tea with its owner Norman E. Lamplugh, dinner with the Holding family in Kensington, on Monday a coach tour from Cadogan Gardens to be shown round the vast HMV record factory at Hayes, then to hosts Mr and Mrs Powell in Earls Court with Gunther Motz, Miss Hearn from Canada and Miss Lewis from Australia. Afterwards all were invited to a magnificent Ball given by the Goldmiths Company where Winston spent time with Motz, Miss Johnson from England and Miss de Charme from Paris. Tuesday took them to Twickenham for the varsity rugby match where Oxford’s kiwi captain Malcolm Cooper excelled against Cambridge; in the evening to a studio performance at the Gate Theatre by Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies. Wednesday was set for lunch in Kensington with the family of Sir John Gilmour the recent Home Secretary and dinner in the City with the Grocers Company where the speakers were Jack’s old friend Lord Bledisloe and Miss Macdonald of the Isles. Thursday’s trip from Cadogan Gardens was to Hatfield House with a personal tour conducted by the tough old Marchioness of Salisbury. On Friday the academic aspirants were dispersed to their hosts in the country for the weekend. And Jack could join in for a break at last after his busy week in the Lab. The context in which we discover this information is through the life of John Wesley “Jack” Mitchell, FRS, (1913-2007), an outstanding international scientist from New Zealand whose work in chemistry and physics examined the properties of materials and extended the possibilities of high speed photography [left].

The context in which we discover this information is through the life of John Wesley “Jack” Mitchell, FRS, (1913-2007), an outstanding international scientist from New Zealand whose work in chemistry and physics examined the properties of materials and extended the possibilities of high speed photography [left].It turns out that Lady Ryder's scheme encompassed far more than simply caring for servicemen (and presumably women) during the war, and it seems natural to think that, with Ryder hosting teas and large parties—note that a "throng" of international personalities on that "Saturday night" mentioned above—the Mills family must have been involved quite closely with the scheme and attendant at parties and dances, and perhaps even the scheme's outings.

This fits well with what we know about the Mills sisters: Posh, even a bit snobbish, and socially comfortable with a wide range of individuals from many different walks of life and diverse nationalities, especially peerage. One look at the list of croquet players they played with and against while situated at their retirement home in Budleigh Salterton attests to that!

Speaking of croquet, an Australian player by the name of Dr. Harold J. Penny took to the lawns against the Mills family (including George), and he was the subject of the second message I received this morning, this one from Dr. Robert Likeman:

Harry,

Here is a brief bio of Harold Penny from my forthcoming book. It may help to fill in some of the blanks in your blog.

Kind regards,

Robert

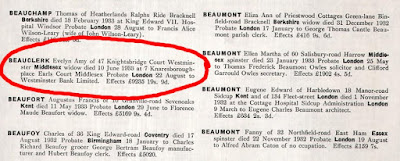

1. PENNY, Harold John, Captain (1888-1968). MB BS Adel 1913. Penny was born in Semaphore SA, the youngest son of Charles James Penny, a teller in the Bank of Adelaide, and his wife Emma Stephens. He was educated at St Peter’s College and Adelaide University. He rowed for the University in 1911 and again in 1912. After graduation he completed his residency at Adelaide Hospital and the Children’s Hospital. During the former term, he made the papers three times for treating patients with gunshot wounds. He was commissioned in the RAMC in March 1915, and sailed for England on the RMS Mongolia. The first thing that he did on arrival in England was to get married, to Winifred Annie Lake from Bristol. Penny was promoted Captain in March 1916. He returned to Australia after the war, and set up practice in Nailsworth SA, but evidently Winifred did not ca

re for Australia, and the couple returned to England. They were divorced in 1925 on the grounds of Winifred’s adultery with a dentist, Frederick Rowat. The same year Penny married a vicar’s daughter from Harrow-on-the Hill, Mary Violet Ridsdale (1901-1974). They returned to Nailsworth, but in 1928 announced their intention of moving to Western Australia. It is uncertain how long they remained there, but before 1938 they had returned to England to settle at Tunstall, Staffs. Penny was a world class player of croquet. He died in Bournemouth in 1968.

re for Australia, and the couple returned to England. They were divorced in 1925 on the grounds of Winifred’s adultery with a dentist, Frederick Rowat. The same year Penny married a vicar’s daughter from Harrow-on-the Hill, Mary Violet Ridsdale (1901-1974). They returned to Nailsworth, but in 1928 announced their intention of moving to Western Australia. It is uncertain how long they remained there, but before 1938 they had returned to England to settle at Tunstall, Staffs. Penny was a world class player of croquet. He died in Bournemouth in 1968. Dr Robert Likeman

Thank you, Dr. Likeman!

Interestingly, the news reports we read involving Dr. Penny were, indeed, regarding gunshot wounds, a subject in which he obviously became an expert. It would then be wholly natural that he would have been highly desirable as a medical officer during the war.

Dr. Likeman is Director of Health for the Australian Army and the author of Gallipoli Doctors: The Australian Doctors At War Series, Volume 1 (First Edition 2010, Slouch Hat Publications, McCrae, Victoria), and I presume Penny's biography will be found in Volume 2. Dr. Likeman (LtCol, CSM) is the author of several other books on Australian Military History that can be found at the Slouch Hat Publications website. Volume 1 was awarded a Silver Medal in the New York Independent Publishers Awards earlier this year.

(Oh—and just an aside regarding the film A Matter of Life and Death (Stairway to Heaven in the U.S.): It starred David Niven, whose mother, Etta, coincidentally was dying in a nursing home in Kensington along with Revd. Barton R. V. Mills, father of George Mills, when the Mills family patriarch passed away in 1932!)

(Oh—and just an aside regarding the film A Matter of Life and Death (Stairway to Heaven in the U.S.): It starred David Niven, whose mother, Etta, coincidentally was dying in a nursing home in Kensington along with Revd. Barton R. V. Mills, father of George Mills, when the Mills family patriarch passed away in 1932!)It really is wonderful to be writing about the life and times of George Mills once again! Should you have any information, theories, details, ideas, suppositions, hypotheses, or just want to discuss George or his family and friends, please let me know at the e-mail address, far above, to the right.

Many thanks!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)