Having finished The Road to Timbuktu, I've diverged from the path of Lady Dorothy Mills and begun reading The Apache Girl by Arthur Mills, her husband and elder half-brother of George Mills. It was first published in 1930.

Now, I know we've seen that Lady Dorothy's marriage may not have been all bliss, but perhaps the fact that divorce and marital infidelity keeps cropping up in the relatively little I've read of her writing is purely coincidental.

On the other hand, I had read less than three pages of The Apache Girl last night when I came to this, regarding our hero, Harry Rolyat, a British art dealer who has inherited a huge estate, Flairs, and a priceless collection of Chinese porcelain from an elderly client of his:

Curiously enough there had been no proviso in the old lady's will about not selling the porcelain or ultimately bequeathing it to the nation. Harry was perfectly at liberty to sell Flairs and all its treasures any time he wished. There was, however, a codicil to the will that could affect him very materially. Brought up in a strict Victorian era, the old lady, in the later years of her life, had been deeply shocked by modern standards of conduct. The number of divorces that had taken place immediately after the war had filled her with horror. And though well pleased with Harry's marriage, she had seen fit to safeguard his future—as she thought—by inserting a clause in her will that in the event of his marriage being dissolved the property she had left to him, or any money accrued to him through the sale of it, should revert to the next of kin.

It was a surprising codicil for a shrewd, worldly wise old woman to make. For Harry said, when he told Meriel [his wife] about it: "She knew we married for love; why should she think we should need money to keep us together now?"

To which Meriel answered: "Well, money is always useful."

A page later, Harry is silently ruminating on his marriage when the narrator of the story adds: He wondered whether this money they had now was really making them any happier. Still, this was simply the beginning of the book, and it's a book pegged as an adventure. Things would surely begin to unfold more quickly, and the pace was bound to become less contemplative, right?

Still, this was simply the beginning of the book, and it's a book pegged as an adventure. Things would surely begin to unfold more quickly, and the pace was bound to become less contemplative, right?

After Harry dances and sips champagne with a mysterious, intriguing blonde in a Parisian night club [at his wife's behest, might I add, while she entices another man], we meet a murderous apache gangster [depicted in stereotypical garb, left] who has escaped from his shackles on Devil's Island and paddled away on a barrel to the coast of Central America. He has made his way back to Paris where he ends up in Harry's iron choke hold after we discover he's the evil and abusive husband of the blonde—and, yes, we're still in Chapter 1!

Soon, in Chapter 2, Harry and his wife are back at their Paris hotel:

For a while he watched his wife intent on her beauty preparations. The thought flashed oddly through his mind that there had been a time when Meriel had never put cream on her face until after he had kissed her. What days those had been when no other woman in the world existed for him and no other man for her! But one could not expect that sort of thing to last forever.

And, via the narrator, we soon know:

They had completely redecorated Flairs, putting in central heating, electric light, and several bathrooms. It had been necessary, for the old Baroness Mollot, in spite of her wealth, had lived there under Victorian conditions, refusing to have even a telephone installed. New carpets and wallpapers had been bought, ceilings repainted. These matters Meriel had supervised, ordering everything of the best without question as to price. She was the same over clothes; her frocks, some of which she would wear only once, were fantastically expensive. Though it did not matter, they were for the moment almost without ready cash.

I'm sorry, but I'm thirty-some pages into this book, and that's a lot of talk of divorce and marital discontent. And at this same time, 1930, we've read that Lady Dorothy is discussing faithless, divorce-minded Arab husbands in her autobiography and in the newspapers, making it clear that one needs to have one's eyes wide open before entering into a marriage! The last excerpt above is actually not lifted from the married life of Arthur and Lady Dorothy, but appropriated from the lives of her father and mother, Robert Horace "Robin" Walpole, heir to the Earldom of Orford, and his American bride, Louise Corbin, a daughter of American railroad magnate D. C. Corbin [right].

The last excerpt above is actually not lifted from the married life of Arthur and Lady Dorothy, but appropriated from the lives of her father and mother, Robert Horace "Robin" Walpole, heir to the Earldom of Orford, and his American bride, Louise Corbin, a daughter of American railroad magnate D. C. Corbin [right].

Walpole inherited the Earldom and its estates, Mannington and Wolterton Halls, both of which were in states of neglect and disrepair. Countess Walpole [née Corbin] worked to modernize both edifices, updates that were covered famously by the press. Here's a snippet of what is really a rather lengthy and ghastly tale for another time, from historylink.org:

In 1888 Louise married Robert Walpole, 12 years her senior, soon to be the fifth earl of Orford, making Louise a countess and the mistress of Mannington and Wolterton halls in Norfolk, England. At first glance, the marriage bears the marks of a late nineteenth-century stereotype: “rich American girl marries into English aristocracy, replenishing the sagging fortunes of her husband and his family while providing her tycoon father with titled in-laws to add luster to the company letterhead.”

Typical of many such English noblemen, Robert Walpole was land-rich but cash-poor, and the two stately homes he soon inherited were badly in need of restoration. D. C. Corbin was 56 at the time of his daughter’s marriage, and the earl could reasonably have expected her to outlive her father. However, in 1909, after two decades as a minor ornament of English society, Louise died…

When D. C. Corbin died in 1918, he left to that branch of the family only a trust fund for his granddaughter [that would be Lady Dorothy] from which she could not draw income until the death of her father, the earl. In the meantime, Lord Orford’s diary makes it clear that, during his marriage, little money had been forthcoming from his rich American father-in-law.

So, in 1909, Lady Dorothy was left motherless at the age of with a father who, among many other faults, had spent far more in his life than he earned or inherited. She was 18 years old, barely two years from having been presented to society, when her mother, according to the New York Times, "dropped dead."

Seven years later, Lady Dorothy marries Arthur Mills, already described as "a handsome and well connected man but with little money." The couple pound out stories for periodicals and newspapers to make ends meet at home, and, as we know, each publishes a book in 1916. Money, though, seems as if it would have always been a concern for Lady Dorothy's family, and as a bright, only child, I'm certain she'd have been aware of discussions regarding expenses, finances, and resentments. Perhaps I should have written that 'lack of money' was the concern, although it didn't stop the Walpoles from traveling internationally and leading the lifestyle of sophisticated modern gentry.

Money, though, seems as if it would have always been a concern for Lady Dorothy's family, and as a bright, only child, I'm certain she'd have been aware of discussions regarding expenses, finances, and resentments. Perhaps I should have written that 'lack of money' was the concern, although it didn't stop the Walpoles from traveling internationally and leading the lifestyle of sophisticated modern gentry.

And we have seen the stately home of Arthur's grandfather, Arthur Mills, Esq., M.P., in Cornwall [left], and know that Mills' family of origin was quite wealthy, even if just a few short years later he came back from France wounded and relatively light of cash.

Money certainly seems to have been a concern of both young Lady Dorothy, 25, and limping war hero Arthur Mills, aged 31, circa 1916. By 1930, however, there seems to be plenty of money—but she is recovering from what apparently was a devastating car accident, he is just about to be caught in an adulterous liaison, and each is writing of love, marriage, and divorce with an edge as sharp as a razor and all the tenderness of a bayonet.

Back to the book:

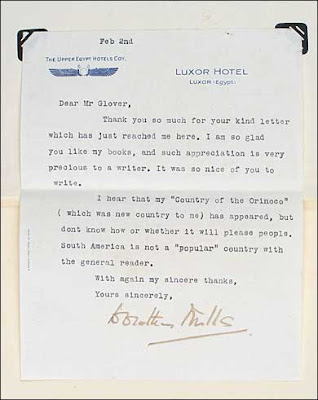

The pleasures of the rich, hunting, shooting, the best of everything in the way of houses and servants, had been theirs by chance of birth. And yet, when they married and had to forego everything, neither had minded. They had often talked of what they would do, in those days, if they ever did have any money. Hunting was sport of which each was passionately fond. And then money had come to them and Flairs—a beautiful house in one of the best hunting centres of England. What had they done with it? This winter they had gone away in the very middle of hunting season, because Meriel said she wanted to see Egypt.  Egypt, huh? That was obviously a bone of contention already, although Lady Dorothy's letter pictured at the right was written later from Luxor, when she was still planning to write another book that never quite came to fruition. She applied for that Egyptian visa alone in 1931, without an acccompanying one for Arthur.

Egypt, huh? That was obviously a bone of contention already, although Lady Dorothy's letter pictured at the right was written later from Luxor, when she was still planning to write another book that never quite came to fruition. She applied for that Egyptian visa alone in 1931, without an acccompanying one for Arthur.

Is Arthur Mills writing an exciting, mysterious adventure novel here, or simply brooding aloud? And Lady Dorothy was renowned for her love of hunting and fishing from her earliest childhood. I assume Arthur hunted as a boy in Cornwall and Devon as well. I'll finish with this excerpt:

His body was tired but his mind would not let him rest. Where was all this leading to—that was the thought that obtruded itself persistently. In the eyes of the world he and Meriel had everything to make them happy—a beautiful home, plenty of money, and no worry about illness. They had not in fact, in the literal sense of the word, a care in the world. And yet Meriel was not really happy, not like they used to be when they were living hand to mouth.

Knowing how the marriage of Arthur and Lady Dorothy came out, that's all so very sad. I know that danger, mystery, and mayhem await in this somewhat melodramatically written adventure, but I still can't help wondering about page 250, the last one: Will Harry and Meriel have resurrected their flagging marriage, or will have taken up with the beautiful night club blonde, Yvonne Levard?

What was Mills' vision of the future back then in 1930? It'll be interesting to see if he'll reflect on it as thoughtfully and as often as he has his past—through just these first 36 pages!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

Sam, are you familiar with Pre-Code Hollywood films? They start at the beginning of the sound era and end around 1934, and they are mainly known for dealing with adult subjects before censorship. And two of the more common subjects they explored were infidelity and divorce. The Apache Girl sounds like it could have been a Pre-Code Hollywood film.

ReplyDeleteA good book to read about that era is Sins in Soft Focus.

And by the way, your blog posts are answering questions I've been wondering about for years dealing with Lady Dorothy Mills.