It's clear from what we learned last time that Egerton Clarke did not come from a well-to-do family, or even a family with a moderate income. When his father, Percy Carmichael Clarke, passed away while serving as Chaplain in Dinard, France, in 1902, Egerton was just three years old. His mother was 45 years old and had another child, 14-year-old Dorothy Mary Clarke.

One day, Egerton was a three year old playing at his home on the balmy coast of France and probably being tended to by his nurse, and in the next his father was dead, his family uprooted, and his life changed forever.

As the orphan child of cleric, Egerton was able to attend St Edmund's School in Canterbury (or Blean?), which had changed its name in 1897 from the The Clergy Orphan School.

His mother, Emma Anna Piper Clarke, was the youngest daughter and second youngest child among a brood of 11 children.

His mother, Emma Anna Piper Clarke, was the youngest daughter and second youngest child among a brood of 11 children.Her father and mother passed away (in 1887 and 1893 respectively), and she had departed the farmland that had been her home at Bishops Stortford in Hertfordshire to become the wife of an older man, the Reverend Clarke, in Norwich, Norfolk.

After that, it seems she got lost in the shuffle of siblings' deaths, family squabbling (I don't think those multiple, fraternal partnerships involving breweries that we read about last time became dissolute over nothing), and space and time—by 1902, my hunch is she truly was not in the forefront of any family member's mind. They all had other things to worry about besides a youngest sibling that, frankly, many of them hardly knew.

By the time Emma Anna was 10 years of age, her five oldest siblings would have been 18 or older. By the time Emma was 18, eight of them would have been 21 or older.

And, sadly, by the time Emma was widowed at 45, three were dead—including the two of the three youngest (Herbert and Clement), who had been closest to her in age. Within ten years, three more would pass away, leaving a married sister, two spinster sisters (who were 6, 8, and 12 years her senior), and an older brother, Ebenezer, who'd run a public house for tramps and was living with her brother Herbert's widow.

What happened to Egerton's sister, Dorothy, is open to conjecture. She seems to have disappeared into the mist, as they say. We also are unsure of Emma Anna's whereabouts between 1902 and 1917—15 long years—but we do locate her when Egerton goes to war.

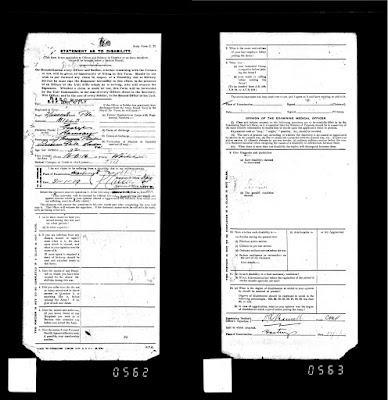

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke became a member of the army at Southampton on 20 September 1917, and his date of service was recorded from 12 November of the same year. His occupation is recorded [left; click any image to enlarge] as "Scholar," and he was 18 years and 54 days of age. He had been classified as B III and posted to the Devon Regiment in Exeter the next day.

Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke became a member of the army at Southampton on 20 September 1917, and his date of service was recorded from 12 November of the same year. His occupation is recorded [left; click any image to enlarge] as "Scholar," and he was 18 years and 54 days of age. He had been classified as B III and posted to the Devon Regiment in Exeter the next day.Two days later, on 15 November, Egerton was transferred to the Army Pay Corps in Winchester. His next of kin is cited as "Mrs. P. C. Clarke, Thorley Wash, Bishops Stortford, Herts"—the farm of her widowed (and wealthy) sister, Hannah.

We know someone else who had been transferred into the A.P.C. around that time: George Ramsay Acland Mills, who had been sent to Winchester on 16 April 1917.

We also know from our study of his First World War records that George would eventually be put out of the A.P.C.: Mills was compulsorily and involuntarily transferred to Dover on 19 September 1918. After beginning his service at the Rifle Depot in 1916 as an acting lance corporal, by 1918 George had become a mere "fatigue man" at Winchester—not very well thought of, and a man who would not be considered for promotion.

Let's take a closer look, though, at what little we know about the time Egerton spent at Winchester.

He spent eight days hospitalized at the Central Military Hospital in Winchester with influenza from 18 January 1918 through 26 January. There were no remarks recorded about his stay.

He spent eight days hospitalized at the Central Military Hospital in Winchester with influenza from 18 January 1918 through 26 January. There were no remarks recorded about his stay.Soon, he spent 13 days at hospital—3 June 1918 to 15 June 1918—with tonsillitis, with the remark: "Cleared up on treatment."

Despite the terror that attended the influenza epidemic that year, Egerton really seems to have borne up well, and these hospitalizations on the surface don't seem to have been very serious.

However, on 20 August 1918, Egerton was hospitalized for "V. D. H.": Valvular Disease of the Heart. The attending physician's notes easily can be seen to say: "Anaemic. Systolic bruit at apex. Conducted into axilla. Heart dilated. Attacks of epitaxis frequent. Very short of breath and exertion. Unfit for further service."

Now, Egerton was admitted on 8 August, but we do not know when that diagnosis was made—perhaps the same day.

On page 1685 of the Journal of the American Medical Association (Vol. 78, No. 22) from 29 November 1919, there is an article by Fred M. Smith, M.D., of Chicago entitled, "Tachycardia following influenza pneumonia." You can read the article itself by clicking HERE, but the gist is that many soldiers, after suffering influenza in 1918, were beset by increased pulse rates and other maladies, leading, as the author writes, to some "who had been discharged from the hospital to quarters or duty were returned for observation. Some complained of shortness of breath, weakness, dizziness, and palpitation of the heart on exertion."

Egerton's third hospitalization may have been due to a different cause than those above—he was admitted suffering epitaxis, or nose bleeds—but while the onset of symptoms may have been precipitated by his bout with influenza, his problems were likely to have been organic in nature. Of a case Dr. Smith studied in which the soldier suffered "Organic Heart Disease," he writes:

Egerton's third hospitalization may have been due to a different cause than those above—he was admitted suffering epitaxis, or nose bleeds—but while the onset of symptoms may have been precipitated by his bout with influenza, his problems were likely to have been organic in nature. Of a case Dr. Smith studied in which the soldier suffered "Organic Heart Disease," he writes:The course and physical findings of the patient differed markedly from that of the other men. He had a pulse rate of 140 per minute, a definite cardiac enlargement, and a blowing systolic murmur at the apex that was transmitted to the axilla. The findings were associated with shortness of breath, palpitation of the heart, and a feeling of exhaustion on exertion. These symptoms disappeared on rest in bed.

"Rest in bed."

Egerton Clarke had a ticket out of the army: His bad ticker.

Egerton Clarke had a ticket out of the army: His bad ticker.When Egerton had reported to Winchester, his medical examination reported that he was 5 feet, 11 inches tall, 135 lbs. (very slim!), and in "Good" physical condition. His vision was excellent.

Egerton's chest size was 34" with an expanded range of 3"—completely average.

Unfortunately, that Army Form B. 178., filled out upon his arrival in the army, had already noted that Clarke suffered from a "Mitral Systolic Murmur" that was "½ (inch) under chest." Egerton's problem was, indeed, organic. Interestingly, the President of the Medical Recruiting Board passed him into service, but classified him as a "Grade III."

We gain more information on Egerton from his Army Form B. 178a., with the wonderfully descriptive title: Medical Report of a Soldier Boarded Prior to Discharge or Transfer to Class W., W. (T), P., or P. (T), of the Reserve.

Aside from the usual name, rank, and serial number, it states that Egerton's Former Trade or Occupation immediately before serving had been "Student at St Edmunds, Canterbury."

We find him being discharged due to "293 V. D. H.," and that he'd had the disability since "Childhood… in the South of France."

A history of the Facts of the case on this form reads somewhat differently than what we saw recorded above. Of Egerton, a physician wrote:

He states he has always had a weakness in his heart + was marked Grade III when he was called up on leaving a public school. He was sent to Winchester. In Jan 1918 he reported sick with pain in his chest + throat trouble. He was sent to Central M. H. Winchester. After 1 week he returned to duty. In July he reported sick + was in H. with tonsillitis [and] influenza. After 2 weeks he returned to duty. His heart became worse, he had attacks of giddiness+ breathlessness. On 20 – 8 – 18 he was sent to Union Infirmary H. + on 5 – 9 – 18 he was transferred to Bed X. H. Winchester.

He states he has always had a weakness in his heart + was marked Grade III when he was called up on leaving a public school. He was sent to Winchester. In Jan 1918 he reported sick with pain in his chest + throat trouble. He was sent to Central M. H. Winchester. After 1 week he returned to duty. In July he reported sick + was in H. with tonsillitis [and] influenza. After 2 weeks he returned to duty. His heart became worse, he had attacks of giddiness+ breathlessness. On 20 – 8 – 18 he was sent to Union Infirmary H. + on 5 – 9 – 18 he was transferred to Bed X. H. Winchester.The form was stamped at the War Office on 30 September 1918. He had been placed in "Grade IV" ("unfit for further service of any kind") by the Medical Board on 25 September.

Egerton had been demobilised officially on 28 September 1918. He would apply for a small pension of 20% which would begin on 1 October 1919 and last for 26 weeks based on the 321 days he had served.

To review: Egerton's third and final trip to the military hospital occurred on 20 August 1918. He was sent to the infirmary hospital on 5 September 1918.

George Mills was "compulsorily transferred" out of the Army Pay Corps [below, right] on 9 September 1918, just a few days after Egerton had been sent to Union Infirmary Hospital—and the only institution I can find by that name was 238 miles away in Bradford, Yorkshire.

That's quite a long way to send a convalescing patient. Perhaps the Medical Board convened to approve or disapprove discharge cases there and only there. Perhaps, though, there was another reason that a great distance from Winchester was deemed necessary by September 1918.

That's quite a long way to send a convalescing patient. Perhaps the Medical Board convened to approve or disapprove discharge cases there and only there. Perhaps, though, there was another reason that a great distance from Winchester was deemed necessary by September 1918.George Mills, a B III like Egerton and with health problems of his own, would have become fast friends with Clarke. Both were educated lads, and both were the sons of clergymen in the Church of England. Both were relatively tall for that time, but neither was a robust man.

Both would have been doted on as youths, the youngest sons of their mothers, both born worrisome problems: Clarke, a weak heart and Mills a speech impediment.

Both may have had trouble fitting in with the other clerks and soldiers in a segment of the army that was populated to a large degree by women. And both were a bit too sensitive and ill-prepared for survival in an environment that, at least involving males, could be hostile and physically demanding.

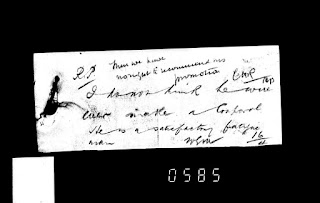

Clarke was simply not around very long; he served under the Colours less than a year. Mills had been around long enough—since 1916—to have presented a poor impression of himself to the military already. In fact, on the very day that Clarke was discharged for hospital on 15 June 1918, Mills was described [below, left] by an officer as "not much use, I fancy."

Perhaps that was just a coincidence, but Clarke had spent some three weeks away from his duties by then, and George was virtually 'useless.' It appears that Egerton helped Mills make more use of himself than George otherwise might have. If Clarke helped George survive in an oppressive environment, then one easily can see that completely losing Clarke later—a transfer to Bradford, followed by a discharge home—would have hit George extremely hard.

Perhaps that was just a coincidence, but Clarke had spent some three weeks away from his duties by then, and George was virtually 'useless.' It appears that Egerton helped Mills make more use of himself than George otherwise might have. If Clarke helped George survive in an oppressive environment, then one easily can see that completely losing Clarke later—a transfer to Bradford, followed by a discharge home—would have hit George extremely hard.And as Mills was barely a satisfactory "fatigue man," at the very bottom of the regimental food chain, any slip in his performance would have had him sent out of the A.P.C. posthaste.

And it did. Losing his friend Egerton must have been devastating.

Interestingly, George's "place of casualty" is listed above as Watford—presumably in Hertfordshire, and a place we've been reading about in the last few entries.

George would eventually be hospitalized himself for Dhobi's Itch (probably ringworm), and finally demobilised on 19 February 1919.

Would the paths of Egerton Arthur Crossman Clarke and George Ramsay Acland Mills, both late of the Army Pay Corps and serving under the Colours for the duration, eventually cross again?

We know they will, and we'll see where and how next time. See you then.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)