The other day we took a look at one of the first pages of writing that author George Mills published: The preface to his first novel, Meredith and Co., in 1933. There we examined just who "Mr. H. E. Howell" might have been.

Today, we'll take a look at the other name in that preface, "Mr. A. Bishop."

First of all, I don't even want to discuss how many times the characters "a bishop" or "bishop a" appear on the internet. Google will provide "about 126,000,000 results" in about "0.21 seconds." Can you say, "Needle in a haystack?"

I immediately wrote to Magdalen College School, Brackley, and the Old Brackleians for help, but never received replies. Those institutions being my best, and possibly only, resources, the lack of response was truly a sticky wicket.

I trolled telephone directories, sought alumni lists, and grazed travel manifests, birth notices, marriages, and deaths for a year, all to relatively no avail. True, I had some names that seemed more likely than others, but nothing solid.

So, why on Sunday afternoon between mowing our front and back lawns, did I hit upon it? I can't say. It seemed I'd used the same search terms over and over and over (and over, for that matter), but this time received a slightly different result.

I found not an "A. Bishop" who'd been Headmaster at Magdalen College School, but an "A. H. B. Bishop." That was breakthrough, but I also was immediately inundated with "hits" from what appeared to be another A. H. B. Bishop, co-author (with a G. H. Locket) of a pair of science text books.

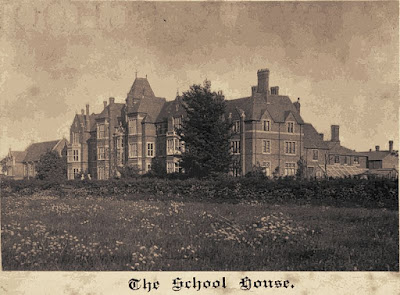

It didn't take long to unearth a link that referred to Bishop as "former" headmaster at Magdalen School, then currently (in that text) headmaster at Warwick School [right]! It also didn't take me very long to leap to the conclusion that we may have found a school where George Mills might have taught during the post-War years (1945 – 1956), during which we know so little about him!

It didn't take long to unearth a link that referred to Bishop as "former" headmaster at Magdalen School, then currently (in that text) headmaster at Warwick School [right]! It also didn't take me very long to leap to the conclusion that we may have found a school where George Mills might have taught during the post-War years (1945 – 1956), during which we know so little about him!You can't imagine how swiftly and excitedly I fired off an e-mail to G. N. Frykman, Warwick School Archivist. Then…

Well, let me let Mr. Frykman pick it up from there:

Dear Sam – I have searched the staff registers of Warwick School, and I cannot find the name of G. R. A. Mills, so he didn’t work here. It is strange, therefore, that you claim that A. H. B. Bishop (headmaster 1936 – 62) encouraged him in his publications. I wonder where you heard that? Bishop was himself, of course, a very successful published writer of chemistry text books. I enclose some paragraphs from Warwick School: A History by G. N. Frykman and E. J. Hadley (2004).

I will admit to some disappointment in failing to find a long-term post-War employer for George Mills, but I feel excited that we can learn about Mr. Bishop. It is both fascinating and instructive for our purposes here: He must have had not only an influence on George as an author, having proofed his manuscripts for Meredith, but had an impact on him as a teacher as well.

Here are some of the "paragraphs" mentioned above by Mr. Frykman:

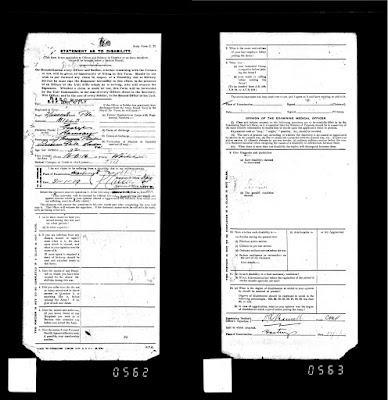

Arthur Henry Burdick Bishop grew up in Cornwall and attended Callington Grammar School. He then served in the army in France, Egypt and Palestine from 1917 to 1920, before going up to Jesus College, Oxford, where he took First Class Honours in Natural Science in 1924. He was a very able chemist, and his two published text-

books (Introduction to Chemistry and An Elementary Chemistry, both written with GH Locket) were widely used throughout the country. His teaching career started at Westminster College, Oxford, but he was soon appointed to the post of Senior Chemistry Master at Radley, and thence to the headmastership of Magdalen College School, Brackley [Bishop's 1933 phone listing there is seen, left].

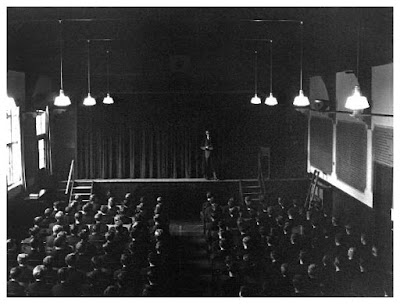

In 2003, Bill Grimes (Warwick School 1930 to 1938) remembered Bishop’s first assembly in Big School in 1936, when he said: “All my life I’ve wanted to be Headmaster of Warwick School, and now I’ve got here, I’m going to stay here!” This remark made more sense when it was discovered that Bishop had applied for the headmastership when it fell vacant in 1933, but had lost out when Percival Smith was appointed. He was certainly not expecting the chance of applying again quite so soon. Like his two predecessors, Riding and Percival Smith, AHB Bishop was offered a salary of £800 (a sum worth about £41,000 in 2003), together with whatever profits he could make from the boarding house. Almost his first action was to use the Junior House, which had been closed in 1935, as additional classrooms and cloak-rooms. Also in his first term, he gathered the whole school together to listen to the funeral of George V on the wireless in Big School. Within two years, he had arranged for the front of the school to be flood-lit – a short-lived improvement in view of the proximity of the Second World War.

Two things immediately strike me regarding Bishop. First, Mills and Bishop had spent time in Cornwall as youths. Mills was born there in 1896, although his family moved to London in 1901. Bishop had been born in 1898 around Woolwich/Plumstead in London, and taken as a boy to Cornwall.

However, Bishop's address in Callington, Cornwall, was actually closer to Devon, where George's kin owned a great deal of land and George had spent much time as a lad, as well.

With an affinity for Cornwall and Devon, and perhaps some common acquaintances, Mills—at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1919 to about 1922—was thinking about a future as a schoolmaster and probably met Bishop [right] while the latter was attending Jesus College at Oxford.

With an affinity for Cornwall and Devon, and perhaps some common acquaintances, Mills—at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1919 to about 1922—was thinking about a future as a schoolmaster and probably met Bishop [right] while the latter was attending Jesus College at Oxford.A second thing that jumps out at me is that, around 1933, Bishop was not appointed to the vacant headmaster position at Warwick School. This is the same time that Mills was set to publish his first book, which, according to advertising in the London Times, was in the stores for Christmas.

Unless things have changed a great deal in education, Bishop would have been considering at length and in depth his philosophies of education, of discipline, of teaching, of management, of selecting personnel, and of business in preparation for his 1933 interviews at Warwick. Helping Mills with his manuscript—especially as the book's fist edition from Oxford University Press was subtitled "The Story of a Modern Preparatory School"—probably helped structure the thinking of both men!

Mr. Frykman continues:

In the 1942 Prospectus, the tuition fees for Warwick boys are given as £5 per term (a 2003 equivalent of £145), and the separate boarding fee as £23 5s per term (£675). Boys from Leamington and beyond had to pay £6 per term. By 1950, as will be discussed shortly, the basic day-boy tuition fee had risen to £18 and the boarding fee to £30 per term, which, with post-war inflation taken into account, were equivalent to £350 and £600 per term in 2003. The tuition fee in 1950 was, in real terms, less than 20% of its value 50 years later. The most likely explanation for this lies in the low salaries paid to teachers at the time and in the fact that the boarders were still subsidising the day-boys.

Although during the Second World War, and beyond the scope of Bishop's editorial relationship with Mr. Mills, the paragraph above about Warwick School [pictured below, left, with Bishop addressing the boys] does much to give us insight regarding our investigations and awareness of preparatory schools such as Warren Hill School, Windlesham House, and elsewhere.

In addition, we have a better idea of the post-War situation for men like Mills, fellows who had been pre-War schoolmasters:

In addition, we have a better idea of the post-War situation for men like Mills, fellows who had been pre-War schoolmasters:The school that greeted the end of hostilities retained only nine of its 1939 staff, though a further six eventually returned from the Forces. Inevitably, the staff body had been drastically affected by the war, and stability was desperately needed. In fact, for many, especially the younger men, the post-war period offered great opportunities, and it became increasingly the case that teachers did not stay a long time in their posts before moving on, either to promotions elsewhere or to other professions. There were, in short, to be fewer Mr Chips.

Now, we know from Dr. Tom Houston at Windlesham House School, that instability in the teaching ranks was characteristic of the 1920s as well. It would be interesting to know if the situation stabilized in the 1930s, but my hunch would be that it did not much: Schools in England failed during the Great Depression, and masters would have been scurrying for new positions as the rumour mill turned. In fact, of the schools at which George Mills taught, only Windlesham would survive until today.

George Mills, we know, had had a short "career" as an officer and paymaster in the Royal Army Pay Corps during WWII, and had had at least a modicum of training as an office clerk in the First World War. Couple all of that with the fact that it was difficult for schools to retain staff members after the war, and that they apparently often lost them to "other professions," and we… are still left with little direction as to what Mills did after the war. Did he teach? Work in an office? All of these options seemto have been very open to him.

In October 1959, twenty-three years after his appointment as Headmaster, Arthur Bishop was able to report to the governors:

The school is in good heart. For the first time there are well over 700 on the roll. The Junior School and Lower School are overflowing, and the Sixth Form is larger than ever. Both boarding houses are more than full.

At Advanced Level we gained 87.5% passes. At Ordinary Level subject passes improved from 54% in 1957 and 60% in 1958 to 69%. Mr Beeching deserves special mention for the outstanding science results.

The music of the school – orchestral and choral – is improving rapidly. The CCF maintains its high standards. Discipline is good, and the reputation of the school is good. The experiment of admitting boys on Common Entrance from preparatory schools at 13 is going well; the list is already full for next year and a reserve list is being built up.

The music of the school – orchestral and choral – is improving rapidly. The CCF maintains its high standards. Discipline is good, and the reputation of the school is good. The experiment of admitting boys on Common Entrance from preparatory schools at 13 is going well; the list is already full for next year and a reserve list is being built up.Much of the credit for this flourishing state of affairs must go to the Second Master, Mr Dugdale and the staff who are most loyal and co-operative. Theirs is a 6 day week as against a 5 day week in the state schools and they willingly give up time to other activities in the dinner hour and after school. I trust the governors will continue their wise policy of recognising this extra work by the staff in their salary allowances.

When the school became independent it had to improve or fall back on state aid. Our scholarship must, at least, compare favourably with neighbouring state schools and in games, society and tone we must excel. That is why we must have a good staff and pay them well to expect so much of them.

George Mills was probably very much retired at the age 63 when this report was presented in 1959. Again, though, it provides substantial insight into the workings of British schools in the mid-20th century. The staff seems to have stabilized, and teachers were at least beginning to be paid commensurate with their worth.

Here's one last paragraph from Mr. Frykman:

It is fair to say that, of AHB Bishop’s 26 years as Headmaster, the early ones were supremely demanding, given wartime conditions. Contemporaries recall that, though not a logical and consistent thinker, Bishop usually got the right answer, and he certainly saw the school through to calmer waters whilst presiding over a huge increase in pupil and staff numbers, numerous building crises and educational changes. It is, indeed, probably fair to say that he saved the school in 1946… After a brief second marriage to Irene Titcomb in 1965, he died in 1969, at Bladon in Oxfordshire, after a short illness.

When I first read of Bishop's scientific background, and the chemistry texts he first published in 1936 (An Elementary Chemistry by O.U.P., like Mills) and 1939 (Introduction to Chemistry by Clarendon Press), I wondered how he got on with George Mills, an artsy fellow, far more in tune with literature, the stage, music, and the Times Crossword than valences, elements, compounds, and the Periodic Table.

Seeing the description above that Bishop was, quite unscientifically, not always "a logical and consistent thinker" certainly caused a friendship with Mills make far more sense.

[By the way, a coincidence: The books Bishop authored in the 1930s were reprinted in 1956 and 1960, just as the books of George Mills also were reissued during the very same time.]

Former Warwick student R. F. Wilmut has a website called Warwick School in 1961 [click here to visit], and he provides some insight into Bishop [seen, right, during the Queen Mother's visit in 1958] as both a headmaster and as an instructor:

A.H.B. Bishop, Headmaster... was born in 1898, and certainly exemplified the old-fashioned approach to being a Head - not necessarily a bad thing: though formal and perhaps a bit rigid in his attitudes he was approachable and certainly very fair-minded. I did once see him go into a near fury over a slightly persistent question (in one of his regular Q & A sessions at the end of his Religious Knowledge classes) over being allowed to wear duffel-coats instead of the regulation navy raincoats: he actually referred to schools who allowed this as 'going to rack and ruin'.

A.H.B. Bishop, Headmaster... was born in 1898, and certainly exemplified the old-fashioned approach to being a Head - not necessarily a bad thing: though formal and perhaps a bit rigid in his attitudes he was approachable and certainly very fair-minded. I did once see him go into a near fury over a slightly persistent question (in one of his regular Q & A sessions at the end of his Religious Knowledge classes) over being allowed to wear duffel-coats instead of the regulation navy raincoats: he actually referred to schools who allowed this as 'going to rack and ruin'.Many of the things I disliked about Warwick - the emphasis on games, a certain academic rigidity, and an inflexibility in dealing with boys (not only me) who didn't quite fit the expected mould - must I suppose be laid at his door, as he did exert a close control over the running of the school: to balance this he was always respected for his fairness and his manners, and indeed for firm leadership even if one did not always agree with him.

It must be remembered here that George Mills came from a different generation of schoolboys: A "modern" schoolmaster must have been a rare breed, indeed, in George's experience at the dawning of the 20th century. A man who, instead, stood for children, who was "approachable" and "fair-minded" while being an educational "leader" was something Mills emphasized in his own stories of prep schools. Unfortunately, what he had viewed as "modern" and much improved in 1933, children in 1961 saw as "old fashioned." Time marches on, eh?

For one thing, "games" were clearly a huge focus of the schools written about by Mills. In addition, formality and some degree of rigidity are apparent in most of George's schoolmasters at fictional Leadham House School, and his headmaster in Meredith and Co., Howell "Peter" Stone, likely was a fusion of the attributes of three leaders, Charles Scott Malden at Windlesham, Joshua Goodland at Warren Hill, and Arthur Henry Burdick Bishop, all of whom Mills found most admirable.

More on Bishop and Mr. H. E. Howell soon, but here in the States this is Father's Day weekend, and I've a daughter coming in!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)