George Mills taught at Warren Hill School sometime in the late 1920s. Historians at Windlesham House School [left, now in Brighton, but then in Portslade] believe that Mills was in his first job as a schoolmaster when he spent over a year there, from Lent, 1925, through the end of the summer term in 1926.

Mills published his first novel, Meredith and Co.: The Story of a Modern Preparatory School, in 1933, and since we know from a promotional leaflet he was not on the staff at Warren Hill around 1930-1931, it's likely he would have been employed in Eastbourne sometime between 1926 and 1929. Mills also found himself teaching at The Craig School in Windermere and the English Preparatory School in Glion, Switzerland during those years, but it makes sense to surmise that he made a smaller move from Portslade to nearby Eastbourne before exploring career opportunities farther afield

George's Uncle Dudley Mills had been an officer in the Royal Engineers during George's childhood, and he had been quite a raconteur and world traveler. It's easy to imagine George and his siblings gathered around Uncle Dudley during one of his returns to England, listening intently to stories of faraway lands. For example, Dudley once apparently traveled around China dressed as in Chinese garb, speaking the language, and eating local delicacies.

It's also easy to imagine George sitting in the lounge at Warren Hill or having a pint in Meads at The Ship Inn, listening to Joshua Goodland's tales of travelling around the entire world, and his experiences as he had studied education, architecture, and law to that point in his life. Goodland was the holder of an M.B.E., had designed buildings, taught elementary school, tried important cases, hunted big game in Canada, hiked near the Arctic Circle in Sweden, golfed in Sussex, coached law at Cambridge, sailed around the world, saw San Francisco recovering from the 1906 earthquake, visited modernizing Japan and Czarist Russia before the revolution—well, it probably seemed to George that Goodland had done just about everything!

It's also easy to imagine George sitting in the lounge at Warren Hill or having a pint in Meads at The Ship Inn, listening to Joshua Goodland's tales of travelling around the entire world, and his experiences as he had studied education, architecture, and law to that point in his life. Goodland was the holder of an M.B.E., had designed buildings, taught elementary school, tried important cases, hunted big game in Canada, hiked near the Arctic Circle in Sweden, golfed in Sussex, coached law at Cambridge, sailed around the world, saw San Francisco recovering from the 1906 earthquake, visited modernizing Japan and Czarist Russia before the revolution—well, it probably seemed to George that Goodland had done just about everything!George's own schooling had taken him south to Haywards Heath and his military experience had led him to exotic Dover and Shropshire [below, left].

In Goodland, George may have seen some possibilities for himself and his future that were not apparent within his family of origin. George's father, Rev. Barton R. V. Mills, had been ticketed for university, and eventually a life as a cleric and scholar, while his brother, Dudley, went to military school. My supposition would be that many parents with a pair of sons at the time may have made similar decisions: An education for one, the military for the other.

During the early 20th century, George's father did indeed make a similar decision regarding his own two sons. Barton's elder boy, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, went from Wellington, to Sandhurst, to the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry as an officer. Young George was ticketed for Harrow, where his learned and degreed father and grandfather both had been schooled. It's even possible George ended up in an apprenticeship after he left Harrow in 1912.

We know from his records that the military simply didn't work out for George during World War I. After an initial and quite unofficial stint as a lance corporal, he was kept at the level of "fatigue man" for the duration of the war without any hope of promotion. George enjoyed none of the military success that his brother—who was decorated for heroism under fire—had found in the Great War. The younger Mills had washed out as a clerk. Perhaps he simply was not cut out for the military.

We know from his records that the military simply didn't work out for George during World War I. After an initial and quite unofficial stint as a lance corporal, he was kept at the level of "fatigue man" for the duration of the war without any hope of promotion. George enjoyed none of the military success that his brother—who was decorated for heroism under fire—had found in the Great War. The younger Mills had washed out as a clerk. Perhaps he simply was not cut out for the military.It's difficult to say how well George Mills did when he attended Oxford following his hitch in the military. We know he was there from 1919 through some time in 1922 at the very latest, but there are no records of what he might have studied and no record of him having taken any examinations.

Perhaps George simply was not cut out for academia, either. In a family that seems to have valued the dual career choices mentioned above, things must have looked grim for George Mills in regard to gaining and retaining the genuine respect of his family.

Both the military and institutes of higher learning would seem to organizations which have a great many rules to be followed, expectations to be met, and a fundamental duty to reshape their clients into something different—something better—than they had been upon entering. Routines, procedures, systematic progression, and an institutional socialization would have been de rigueur, and perhaps that aspect of military and academic life was what Mills had the most difficulty with in both.

Both the military and institutes of higher learning would seem to organizations which have a great many rules to be followed, expectations to be met, and a fundamental duty to reshape their clients into something different—something better—than they had been upon entering. Routines, procedures, systematic progression, and an institutional socialization would have been de rigueur, and perhaps that aspect of military and academic life was what Mills had the most difficulty with in both.George Mills was probably not considered an extremely able student when he left Harrow [right] after two years. He was tall, slightly built, and beset with both varicose veins on his lips and a speech impediment. His interaction with strangers—and upon entering Harrow, everyone there must have been a stranger—may have been difficult and painfully protracted by his impediment.

Under the pressure of other boys teasing him or stern schoolmasters demanding answers, he may have continually wilted, unable to effectively communicate, eventually becoming reticent even to try.

Humor would have been a marvelous coping mechanism for George as he grew to know some of the other boys and his masters, but one wonders if he could have made enough people laugh to have deflected what must have been a great deal of cruel teasing, and to achieve academically all he might have at Harrow. He may simply have been in survival mode most of the time (and actually may have spent time after his time at Harrow involved in the harrowing speech therapy and familial support of the day, as depicted at the beginning of The King's Speech [left]).

Humor would have been a marvelous coping mechanism for George as he grew to know some of the other boys and his masters, but one wonders if he could have made enough people laugh to have deflected what must have been a great deal of cruel teasing, and to achieve academically all he might have at Harrow. He may simply have been in survival mode most of the time (and actually may have spent time after his time at Harrow involved in the harrowing speech therapy and familial support of the day, as depicted at the beginning of The King's Speech [left]).Things must not have gone much better for him in khaki, with orders being barked, snappy replies requested, and impatient superiors continually crying, "Spit it out, soldier!" Increased anxiety under pressure, and an inability to communicate clearly and efficiently in the midst of the most brutal conflict that had engulfed the entire planet, could not have been looked upon very favorably by anyone.

Ironically, however, Mills had a keen ear for language and an exceptional facility with its use in manuscript, despite his speech. The characters in his books are realistically articulate in both the King's English and the unique adolescent slang of the era.

Far from being perfect, the student characters in George's stories possess foibles and traits that often lead to trouble—sometimes a less-than-pleasant bout with the Head Master's tennis shoe or being ostracized by one's peers. Mills has insight into the mistakes boys make, but more so, he has insight into how adults could—and in his mind—should handle them.

It is no accident that his first novel bore the subtitle "The Story of a Modern Preparatory School [my emphasis]. "

George, in becoming an educator in the late 1920s, had for all intents and purposes returned to the scene of the metaphorical crime, or at least the very real schoolboy "crimes" that he felt had been perpetrated upon him. George, clearly a part of a new, humanistic, "modern" world of education, would right many of the wrongs that he'd experienced at his own schools decades before. And there is a good reason to believe that Joshua Goodland acted as the lynchpin in developing that goal and career choice.

George, in becoming an educator in the late 1920s, had for all intents and purposes returned to the scene of the metaphorical crime, or at least the very real schoolboy "crimes" that he felt had been perpetrated upon him. George, clearly a part of a new, humanistic, "modern" world of education, would right many of the wrongs that he'd experienced at his own schools decades before. And there is a good reason to believe that Joshua Goodland acted as the lynchpin in developing that goal and career choice.Goodland was living at 144 Ashley Gardens in 1925, although it's difficult to tell exactly when he and his family vacated that address. Ashley Gardens is less than a mile from George's family's residence in Kensington at the time [24 Hans Road], and even closer to where his George's step-brother, author (and veteran of campiagns in France, China, and Palestine) Arthur F. H. Mills, was living with his wife, Lady Dorothy Mills, on nearby Ebury Street.

Given Goodland's proclivity to travel, and being a member of the Royal Geographical Society (also conveniently situated in Kensington), it's quite possible that Joshua was acquainted with George's globetrotting Uncle Dudley or Lady Dorothy. Lady D. already had begun traveling the world in the early 1920s, an activity that led her to become the era's foremost female travel writer/explorer. She published multiple monographs as a Fellow in the society (as well as a books and articles for mainstream periodicals) and was renowned throughout the United Kingdom and much of the world.

Lady Dorothy was the sister-in-law of George Mills, and a great deal of interesting activity—Lady Dorothy's travels, Goodland's own interest in travel, George's return home from Oxford and engagement to be married in 1925, and Goodland's waning interest in practicing law—were centered in less than a square mile of acreage in Kensington. George's fiancée and soon to be wife, Vera Beauclerk, was a granddaughter of legendary Sir Robert Hart and had herself been born on China! It's easy to surmise that the paths of George Mills and traveler Joshua Goodland must have crossed at some point.

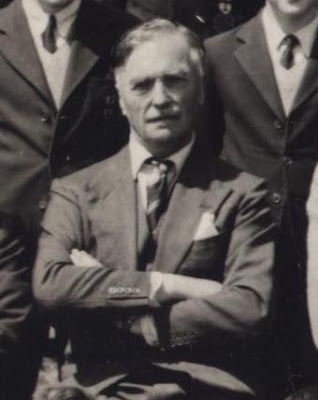

George may have decided to try his hand at teaching just after Goodland had become a partner of F. R. Ebden [left] at Warren Hill, and Joshua actually may have been soliciting additional staff for the preparatory school in Eastbourne. At that time George, who was successfully engaged as in a junior appointment at nearby Windlesham, may immediately have sprung to mind. It's easy to imagine that George—then thirty years of age and gaining confidence as he taught—may have become more comfortable in his skin, and with his speech.

George may have decided to try his hand at teaching just after Goodland had become a partner of F. R. Ebden [left] at Warren Hill, and Joshua actually may have been soliciting additional staff for the preparatory school in Eastbourne. At that time George, who was successfully engaged as in a junior appointment at nearby Windlesham, may immediately have sprung to mind. It's easy to imagine that George—then thirty years of age and gaining confidence as he taught—may have become more comfortable in his skin, and with his speech.The Summer Term at Windlesham House this year (2011) runs from 1 May through 9 July. Assuming it was similar at the time, Mills would have been teaching at Windlesham through the Summer Term, July 1926. If Goodland had connected with Mills earlier in Kensington, it's possible that they became reacquainted during early 1926, possibly during cricket or football matches involving the boys at Windlesham and Warren Hill.

We have always assumed Mills left Windlesham against his will: Perhaps because of the General Strike, perhaps because he was found inadequate, or perhaps because it was discovered he had lied about his Oxon credentials.

Is it possible Mills left of his own accord, eschewing a newly purchased house in Portslade near Windlesham for the chance to work with Goodland in Meads? Mills might even have been lured by a bit more salary or the offer of a free residence, allowing Vera and him to sell their new home in Portslade.

George always had struggled in determining 'what he wanted to be when he grew up.' In Joshua Goodland, he'd have found a somewhat kindred spirit, a man who was had always been wanderer along a circuitous career path that included elementary school assistant, architect, law coach, barrister, schoolmaster, entrepreneur, and eventually, as we know, "sometime Head Master of Warren Hill School," all within a four decade span from 1891 to 1931.

Mills thought enough of Goodland [right] to make the "sometime Head Master" the only person singled out by name in the dedication of his first novel. It's likely the feeling was mutual. It is possible that Goodland saw something in Mills that might never have been noticed before. It is also possible that, even if George's potential had been recognized in the past, Goodland was the first to help him begin to realize it.

Mills thought enough of Goodland [right] to make the "sometime Head Master" the only person singled out by name in the dedication of his first novel. It's likely the feeling was mutual. It is possible that Goodland saw something in Mills that might never have been noticed before. It is also possible that, even if George's potential had been recognized in the past, Goodland was the first to help him begin to realize it.George never made it through Oxford, earning a degree, although that fact didn't stop him from telling potential employers that he had. It may be that he even told Goodland he was degreed. No matter, George suddenly saw possibilities—even the possibility of future success—despite having a made few career changes, and even if he had already turned thirty.

Joshua Goodland was short, gregarious, intelligent, and probably an energetic man with a wealth of talent, but it does seem he his ambition was accompanied by a lack of clear focus.

George Mills had his own set of talents, and a certain charm, wit, intelligence, and affability that eventually drew people to him. Both men were essentially social beings who obviously enjoyed teaching, and they were keen observers of people.

Mills, it seems, also shared Joshua's lack of focus.

The eminently successful Goodland must have been a larger-than-life image and role model to Mills, and it is no wonder George found himself gravitating to the man.

Why Mills soon departed Meads and ended up teaching in isolated and far flung locales like Windermere and Glion is unknown. For whatever reason, however, Goodland was still the only person mentioned by name in the dedication of George's first novel in 1933. It is difficult to believe the two men parted acrimoniously.

We don't know if Mills and Goodland remained close, but we do know that after Joshua's passing in 1939, Mills [left] never published another book despite living until 1972.

We don't know if Mills and Goodland remained close, but we do know that after Joshua's passing in 1939, Mills [left] never published another book despite living until 1972.If Goodland had truly been an inspiration, and if subsequent texts continued to win Joshua's approval for George, Goodland's death may have been a real hurdle that Mills found it difficult to clear.

Mills had lost his own father in 1932, and it is possible that George—failed apprentice, failed soldier, failed academician, and a schoolmaster unable to hold the same teaching position for longer than a year or two—knew he had been a disappointment to his father. Goodland was 23 years older than Mills, and may have become an understanding and sympathetic father figure to George at a time when Mills realized he'd never lived up to his late father's expectations.

It may be a coincidence that George's most noteworthy success—1933's Meredith and Co.—was published on the heels of his father's passing in late 1932, the same year Joshua had lost his brother, Theodore. It may also be a mere coincidence that the book's dedication singled out the older Goodland for his influence on George at that critical point in his life. And it may be that the eventual demise of Joshua Goodland only coincidentally occurred in the very same year that saw the demise of George's career as an author.

But that would be too many coincidences for me to dismiss out of hand.

Mills closed the book (no pun intended at first) on his life as an author in 1939. War was imminent for Great Britain, with a resurgent emphasis on the realm's military. Having recently come to grips with finding a literary success that would have pleased his father—a scholar who had authored and edited texts of his own—Mills still had some unfinished business owing to his failings in the military..

After spending more than a decade as an schoolmaster and author, it was time for George to return to the scene of yet another crime against him: The Royal Army Pay Corps.

But that's a story we already know much of, at least pending access to his Second World War military files.

I'll have just a bit more on Joshua Goodland—a man I believe had as powerful an influence on George Mills as anyone—next time. Then, on to other topics!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)