Ashanti Goldfields Corporation was founded in 1897 by Edwin Cade. Late in the year, principals of the company "dragged and carried 40 tonnes of equipment nearly 200km from the coast to begin exploitation of their new property in Obuasi, in Ghana (formerly known as the Gold Coast)" according to a company website.

The fourth and final Anglo-Ashanti War had just been fought in 1895-1896. After its conclusion, the corporation began devising methods of extracting gold via mining, as opposed to prospecting and then panning for gold found amid the quartz in the rivers.

In 1900, a failed Ashanti Uprising finally solidified British Colonialism in what is now Ghana after the capture of the throne of King Kwaku Dua III [right], the Golden Stool. At the conclusion of those hostilities, the Gold Coast officially became a British protectorate as of 1 January 1902.

In 1900, a failed Ashanti Uprising finally solidified British Colonialism in what is now Ghana after the capture of the throne of King Kwaku Dua III [right], the Golden Stool. At the conclusion of those hostilities, the Gold Coast officially became a British protectorate as of 1 January 1902.According to Wikipedia: "By 1901, all of the Gold Coast was a British colony with its kingdoms and tribes considered a single unit. The British exported a variety of natural resources such as gold, metal ores, diamonds, ivory, pepper, timber, grain, and cocoa. The British colonists built railways and the complex transport infrastructure which formed the basis for the transport infrastructure in modern-day Ghana. They also built Western-style hospitals and schools to provide modern amenities to the people of the empire."

Another website, Mike's Railway History: A Look at Railroads in 1935 and Before, contains the authoritative 1914 writing of F. A. Talbot, who tells the gritty story (well worth reading in its entirety, by the way) of the Gold Coast's first railroad: "It was the discovery of gold which prompted the construction of the first railway on the Gold Coast. Intrepid prospectors braved the pestilential forests and diligently panned the up-country streams. They discovered traces of colour, and, following up the clues, at last struck the main reef of yellow metal at Tarkwa, some 40 miles from the seaboard. The news of the discovery precipitated the inevitable rush, as well as an inflow of capital, but it was no easy matter to gain the alluring gold belt. There were no facilities for transporting the essential heavy and cumbersome machinery to the claims, while the conveyance of the yellow fruits of exhausting labour to the coast was just as laborious. Incoming vessels had to discharge into small boats which ran the gauntlet of the heavy surf and dodged the sand-bars which littered the waterway leading to the interior. They crept up the river with considerable difficulty to a point as near the mining area as possible and there unloaded. The material then had to be tugged, pushed, and carried over rude tracks through the jungle to the mines. By the time the mines were reached transport charges had run away with £40 per ton."

The allure of gold, of course, still drew many potential investors. But there were other difficulties.

"When a nude stick planted by the surveyor has grown into a fully-fledged tree by the time the railway builder arrives, identification is by no means easy," says Talbot of the region's effect on mere surveying. "As the Gold Coast, from its hot, moist climate, is virtually a gigantic greenhouse, the undergrowth thrives amazingly."

Describing the conditions at the end of the 19th century, Talbot writes: "The shore of the Gold Coast is hemmed in by a thick belt of jungle, 150 miles or more in width. To venture into this huge, un-trodden forest demanded no small amount of pluck and determination. The exotic vegetation presented a solid barrier, through which advance could be made only by hacking and cutting, since the jungle was intersected by very few, narrow, and tortuous paths, trodden down by the feet of the natives."

Describing the conditions at the end of the 19th century, Talbot writes: "The shore of the Gold Coast is hemmed in by a thick belt of jungle, 150 miles or more in width. To venture into this huge, un-trodden forest demanded no small amount of pluck and determination. The exotic vegetation presented a solid barrier, through which advance could be made only by hacking and cutting, since the jungle was intersected by very few, narrow, and tortuous paths, trodden down by the feet of the natives."He continues: "Disease was more to be dreaded than any form of hostility or accident. The surface of the ground is carpeted with a thick layer of decaying vegetation—the putrefaction of centuries—and the rainfall, which is severe, has converted this bed of leaves, branches, and dead-fall into a spongy, sodden mass, freely interspersed with pools and swamps, where the mosquito and other pests multiply by the million. Accordingly, malaria is rife; in fact, at that time it held the country more securely against a white invasion than the most cunning and determined tactics of the unfriendly natives."

Talbot opines: "No industrial concern could work under such conditions and show a profit. Accordingly it was decided to drive a railway from a convenient point on the coast to Tarkwa. After scouring the shore line of the Gold Coast from end to end, it was decided to create a terminal port at what was virtually an unknown spot, which then was little more than a native village—Sekondi. It is not a harbour, but merely a small, open bay; but it was the only choice."

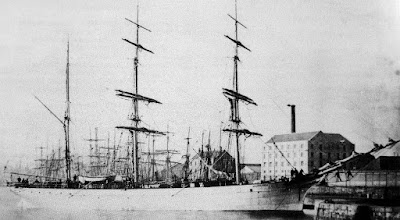

Besides the heat, humidity, constant rainfall, uneven terrain, lack of a a local workforce, and jungle diseases, to get the railway through, almost everything necessary had to be shipped from England: "A vessel laden with supplies put out from Liverpool once every month while work was in progress. The commissariat was a heavy responsibility, bearing in mind the large army of toilers that had to be fed. But the arrangements were laid so carefully that no apprehensions ever arose under this heading, although now and again everything went awry from some unforeseen mishap, such as the total wreck of a supply steamer off the West African coast. Losses in landing at Sekondi, owing to the absence of harbour facilities, were considerable."

Besides the heat, humidity, constant rainfall, uneven terrain, lack of a a local workforce, and jungle diseases, to get the railway through, almost everything necessary had to be shipped from England: "A vessel laden with supplies put out from Liverpool once every month while work was in progress. The commissariat was a heavy responsibility, bearing in mind the large army of toilers that had to be fed. But the arrangements were laid so carefully that no apprehensions ever arose under this heading, although now and again everything went awry from some unforeseen mishap, such as the total wreck of a supply steamer off the West African coast. Losses in landing at Sekondi, owing to the absence of harbour facilities, were considerable."Of the beginning of the venture, Talbot writes: "The first section comprised some 40 miles, but it was as hard a 40-mile stretch as any engineer could wish to tackle. There was the densely-matted jungle, a fearful climate, a fiendish rainfall, and a comparative absence of gravel with which to carry out the earthworks. Englishmen, of course, were in demand to superintend operations; but it proved to be no white man's land in those early days. The deadly climate mowed them down like flies, while some of stronger physique, although they outwitted the 'old man with the scythe,' went raving mad."

In 1900, due to the unrest and uprising, workers from the railway were commandeered to work as porters for the military. Importing new workers from nearby countries was forbidden as it was feared that the new workers might join the rebellion. Work on the railroad came to a standstill.

After the fall of the Ashanti king, construction soon resumed and in May 1901, Tarkwa in the interior finally was linked to the coast. Eighteen months later, in late 1902, the railway had been extended another 86 miles, connecting it with the goldfields of Obuasi. Finally, in September 1903, rails reached distant Coomassie deep in Ashanti country.

Talbot concludes: "The metamorphosis of West Africa constitutes one of the most remarkable incidents in railway history. In few other countries where maps were non-existent, where the rainfall averages as much in a month as during a year in Great Britain, where the forest was untrodden, and where malaria reigned supreme, has so sudden and complete a change been wrought in such a short space of time. In 1897 Sekondi was a handful of straggling mud huts dotting the shore. To-day it is a busy terminal port with sidings, substantial administration buildings, a hospital, and other attributes to a busy growing centre."

Talbot concludes: "The metamorphosis of West Africa constitutes one of the most remarkable incidents in railway history. In few other countries where maps were non-existent, where the rainfall averages as much in a month as during a year in Great Britain, where the forest was untrodden, and where malaria reigned supreme, has so sudden and complete a change been wrought in such a short space of time. In 1897 Sekondi was a handful of straggling mud huts dotting the shore. To-day it is a busy terminal port with sidings, substantial administration buildings, a hospital, and other attributes to a busy growing centre."Due to the adverse conditions, prevalent disease, and the onset of insanity, at least 10 supervising engineers oversaw the construction of the railway.

Once they reached the interior, "transportation charges were [soon] reduced from £40 to £5 per ton, and the effect was felt immediately. The heaviest machinery now could be brought up with ease and installed… Then the development of the mines went forward with a rush."

Before the advent of the railway, Ashanti Goldfields Corporation itself says: "In the first few years [of operation], new discoveries were continually being announced and the erroneous impression arose that many fabulously rich reefs existed beneath the corporation's property. That this was not in fact the case only became clear later, when a systematic survey was made and a reliable picture of the occurrences was obtained."

After the railroad linked the mining fields with the coast, there was the "start of a period of disillusionment. By 1904-5, shareholders dissatisfied with diminishing dividends were becoming sceptical of [earlier] promises of higher output. Disappointment was made keener by the high hopes that had earlier prevailed."

After the railroad linked the mining fields with the coast, there was the "start of a period of disillusionment. By 1904-5, shareholders dissatisfied with diminishing dividends were becoming sceptical of [earlier] promises of higher output. Disappointment was made keener by the high hopes that had earlier prevailed."In 1906, leadership in Ashanti Goldfields changed, and "output was checked for a time in order to allow a vigorous shaft sinking and development programme to be carried out. Henceforth attention was to be directed increasingly to deeper mining. Profits were sacrificed for the next few years and ploughed back into the business. With a rail link to the coastal town of Sekondi, it was now possible to import new improved machinery, including winding engines and headgear. Stores and workshops were built, tramlines in the mines were extended to connect the different workings, and the surface infra-structure was generally much improved. There was slower progress underground, and the capacity of the new stamp mills was not taxed until the discovery in 1908 of an important deposit that came to be known as Justice's Mine. A few months later, the rich Obuasi shoot was cut at level 3 of the Ashanti mine."

Those two years of assessing and improving the mines and mining techniques, and the discovery of new veins of gold must still have required an army of workers and quite a few engineers.

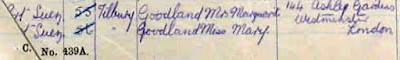

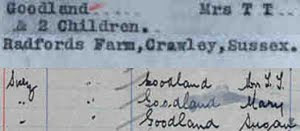

We find that, despite my speculation just yesterday, it is likely that consulting engineer Gillmore Goodland was not in Sekondi on the Gold Coast to visit his brother Theodore. He was probably one of the unnamed but extremely important experienced engineers that allowed the business—today known as AngloGold Ashanti, working not just the Ashanti's Obuasi Mine, but many others throughout sub-Saharan Africa—to thrive even today.

Did he meet Theodore there in 1906? It's hard to say. With mining connections in Australia, as well as family members settling there in 1907, Gillmore in some way must have tipped off his South Seas sailor sibling, Theodore, about the money to be made shipping in and out of Sekondi.

By 1928, Sekondi became a sister city to nearby Takoradi, which had just had a deep water port constructed [left], but the best of Theodore's career was behind him by then. We don't know what claimed the master mariner's life in 1932 at the age of 51, but could it have been a disease picked up on the Gold coast from which he was finally unable to recover?

By 1928, Sekondi became a sister city to nearby Takoradi, which had just had a deep water port constructed [left], but the best of Theodore's career was behind him by then. We don't know what claimed the master mariner's life in 1932 at the age of 51, but could it have been a disease picked up on the Gold coast from which he was finally unable to recover?In his prime, Theodore must have been a valuable captain, able to ship goods in and out of the difficult and at times quite dangerous waters of Sekondi's so-called harbour.

Had he learned of this lucrative opportunity from his brother, Gillmore, who may have been lured away from mining interests in South Africa to help retool the mines in the Gold Coast's interior?

We don't actually know who arrived in Sekondi first: Able seaman T.T. Goodland or consulting engineer G. Goodland. Nevertheless, Sekondi seems to be an unusual and far-too-specific a place for both of these brothers to have connected with it coincidentally.

In addition, it seems highly unlikely that Gillmore Goodland dropped by for a brief vacation. He must have been invited, or perhaps he decided to see if he could become part of what was appearing to be quite a lucrative adventure.

Either way, Gillmore seems even more likely at this point to have been the monetary benefactor of his mother, Frances, and his brother, Cambridge law student Joshua Goodland.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)