Sometimes a person is surprised, and sometimes there's simply a level of virtual shock. That happened to me last evening when my 'first edition' copy of Meredith and Co.: The Story of a Modern Preparatory School by George Mills arrived!

I mean, I knew it was coming, but it was coming from half the world away:

Camberwell Books has confirmed your order.-----

Author: MILLS, GEORGE WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY BROCK, C. E.

Title: Meredith and Co. - the Story of a Modern Preparatory School.

Description: Oxford University Press, London, 1933. 288 pp, coloured frontispiece, minor damage at top of spine, else near fine copy in illustrated, papered boards.. Great C. E. Brock cover illustration showing injured bulldog.

Message from the seller:-------------------------

Harry

Will send

Thanks

Mick

The address of Camberwell Books places it in Victoria, Australia, but the parcel was posted from New Zealand. What a stunningly long journey this book took, both through time and space, to find itself here on my shelf.

I was stunned: The text itself is simply gorgeous. The three watercolour plates by the great C. E. Brock are truly wonderful, and the edition itself is simply a tactile delight! The 'tooth' of the paper upon which the text has been printed is  fine and creamy white enough to actually paint a fine watercolor upon, and the thickly calendared leaves each will stand stiffly and straight up without assistance, defying gravity and age. Were it not for the small tear at the top corner of the spine and a light blue streak across the back, I would think someone had just purchased this book a couple of years ago. The word 'lustrous' comes to mind—this was money well spent!

fine and creamy white enough to actually paint a fine watercolor upon, and the thickly calendared leaves each will stand stiffly and straight up without assistance, defying gravity and age. Were it not for the small tear at the top corner of the spine and a light blue streak across the back, I would think someone had just purchased this book a couple of years ago. The word 'lustrous' comes to mind—this was money well spent!

Take away all I said regarding book publishing during the Great Depression during my reading of Arthur Mills's The Apache Girl: This book is gorgeous, a sumptuous volume that certainly belies the woeful state of the world's economies, circa 1933!

Overnight observations of a few of the details of this beautiful tome lead me to a pair of new ideas.

First, just yesterday I was writing about the possibility of George Mills having been out of work and striving to put food on the table during the bleak years of the depression. I have to say, I've reversed my course on that line of thinking, at least regarding 1933. The quality and sheer presence of this impressive book makes me think that Meredith and Co.—apparently the first tale of its kind in accurately portraying the lives of schoolboys, their behaviors, and their slang and idioms—was well thought of by Oxford University Press. Weighing in at 5 kilograms and measuring 4.5 cm (2 inches!) thick, this appears to be a real heavyweight championship contender of a book, quite unlike the tiny, cheaply produced edition of The Apache Girl, also published in 1933 [its fifth impression since 1930], that I finished reading a few weeks ago!

I had thought that Mills star might have been rising in 1938 and 1939 when he published his final three books, but to me he clearly had a bright future in the eyes of O.U.P. earlier in that decade. They even assigned Brock—one of the top illustrators of the era—to depict full-colour scenes his initial novel. Mills and this book, it would seem, were not considered marginal.

A second thing that jumped out at me was something I'd just been tinkering with: Its preface! Or I thought I had been tinkering with its preface. A quick glance immediately told me that something was different in the original preface, true Mills aficionado that I have become. There were far too many initials!

Just three days ago we looked at the preface of the 1957 edition, and here's Mills's final sentence: "I am also very much indebted to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material."

Here's that same sentence from the 1933 edition, with the additional words in bold face: "I am also much indebted to Mr. E. M. Henshaw for his devastating, but most useful, criticisms, and especially to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material."

Here's that same sentence from the 1933 edition, with the additional words in bold face: "I am also much indebted to Mr. E. M. Henshaw for his devastating, but most useful, criticisms, and especially to that splendid specimen of boyhood, the British Schoolboy, who has given me such wonderful material."

Mr. E. M. Henshaw? Who the heck is Mr. E. M. Henshaw?

'Devastating criticisms'? Useful or not, Mills certainly went out of his way to make sure that we, the readers, knew he had been painfully wounded by those obviously not-so-gently phrased suggestions!

In the short term, Henshaw certainly was acknowledged for his contributions to the publication of Mills's book. In the long term, he ended up being excised like a bad appendix. In 1933, Mr. E. M. Henshaw had been spared the warmth and gratitude Mills had expressed to Mr. A. Bishop and Mr. H. E. Howell in the previous sentence of the preface, while still being acknowledged. In the time elapsed between 1933 and 1950's second impression of Meredith and Co. [then published without its original subtitle] by O.U.P., Mills must have felt any 'debt' owed to Henshaw already had been paid in full, without needing to further acknowledge him in subsequent editions [1950 and 1957].

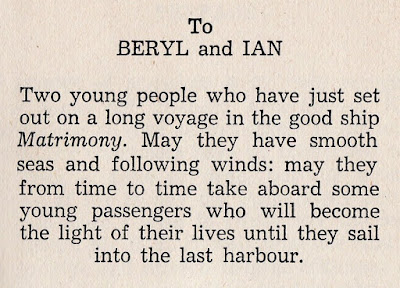

Obviously, Mills had changed. Once known as a fellow who "made people laugh, a lot", by the late 1930s things are quite obviously different. By the decade of the 1950s, painful memories and associations have been and are still clearly being expunged from Mills psyche. It seems that a melancholy process had started when he looked back to Haywards Heath and Parkfield School at the turn of the century for the dedication to 1939's Minor and Major. Later, when King Willow was reprinted in the late 1950s, a dedication to Eaton Gate Preparatory School was scratched in favor of a lyrical ode to the future of now-unknown newlyweds Beryl and Ian.

Was the George Mills of the late 1950s still in a struggle with the present, while at the same time yearning for a nostalgic and comforting past, and hoping with all of his might for a more benevolent future for himself and those he loved?

Looking back at 1939, Mills soon returned to the military, an occupation he'd left behind as a lance corporal in 1919. Returning as a lieutenant, I suppose it would have given him a sense of real security, something I believe he was craving. It also may have provided him with a sense of purpose patriotically, and even spiritually at the outset of a conflict that certainly aroused moral as well as political issues.

Craving that security over his recent creativity, Mills apparently preferred the dependability of a regular paycheck and a dress service uniform [right] to the life of an author and a tweed jacket and a good pipe. One wonders what other occupations may have been tried by Mills between teaching positions to see him through to his next book before the War. Perhaps he needed more security; perhaps he needed it for Vera, his wife. Either way, he had felt a need that was quite real.

Craving that security over his recent creativity, Mills apparently preferred the dependability of a regular paycheck and a dress service uniform [right] to the life of an author and a tweed jacket and a good pipe. One wonders what other occupations may have been tried by Mills between teaching positions to see him through to his next book before the War. Perhaps he needed more security; perhaps he needed it for Vera, his wife. Either way, he had felt a need that was quite real.

In returning to the service, Mills seemed to be not only revising his present life at the time, he seemed to be revising his own expectations for his future, and was even busy blue-penciling parts of his past. The eventual removal of Mr. E. M. Henshaw from the preface of Mills's most popular novel would seem to be a good example of that last bit of speculation.

References to an E. M. Henshaw abound in the 1930's and 1940's, and many of those references pertain to the field of psychology. It would be completely reasonable to believe that a psychologist might have been critical of the behavior of the boys in George's first novel, or perhaps on the possible effects the behaviors in Mills's manuscript might have had on British youth at the time. That would make sense.

However, that E. M. Henshaw was Edna Mary Henshaw, not the "Mr. E. M. Henshaw" who 'devastated' George Mills over his 1933 manuscript.

Mister E. M. Henshaw has been far more difficult for me to flush out into the open.

Thanks in advance for any thoughts or information you might have about all of this…

Case in point: Here's something I've wondered about for some time now. There are so many aspects to the life of George Mills that as I ruminate over what you've shared with me, that new information informs other bits and pieces I know--or about which I've wondered.

Case in point: Here's something I've wondered about for some time now. There are so many aspects to the life of George Mills that as I ruminate over what you've shared with me, that new information informs other bits and pieces I know--or about which I've wondered. Is it possible Beryl & Ian are still in Budleigh and their names simply don't appear on-line for me to find? Mills's dedication uses "long voyage" and "good ship" to describe their matrimonial bliss--a perfect metaphor from a man and for a young couple who all live by the sea!

Is it possible Beryl & Ian are still in Budleigh and their names simply don't appear on-line for me to find? Mills's dedication uses "long voyage" and "good ship" to describe their matrimonial bliss--a perfect metaphor from a man and for a young couple who all live by the sea!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)