This morning begins Super Sunday, an unofficial U.S. holiday, and I'm anticipating the playing of the American football championship game, the Super Bowl. During the baseball World Series and football playoffs so far I've won two pizzas from Carlos, the custodian at my school. He's bet two more, double-or-nothing (a bet he's already lost once), on the Pittsburgh Steelers, winners of two of the last four championships, hoping to get even. I've bet the pizzas owed me on the Green Bay Packers, the only team owned by its fans—the residents of tiny Green Bay, Wisconsin—and not a corporate conglomerate or egotistical multi-gazillionaire.

Last year I had a similar bet on the Indianapolis Colts, favored against the New Orleans Saints. Throughout the years, I've never been able to pick a Super Bowl winner to save my life, so its safe to say Carlos will likely owe me nothing at the end of the day. Betting my pizzas on the favored "cheeseheads" from Wisconsin almost guarantees that the Steel City will take away the trophy.

My only real chance of being involved in a victory today rides on my wife Janet's chili con carne. The host of the party we'll attend, my colleague Debbie, holds an annual Chili Cook-Off Contest. Last year Janet took the 2nd place ribbon, and this year she's looking to come home with the title!

Anyway, shifting to another field of play, while looking over my vast, panoramic Excel spreadsheet of croquet opponents, partners, and results, a few names do jump out. They may not have been the most regular friends or foes of George, Agnes, and Violet Mills, but they're noteworthy.

First, let's introduce ourselves to the Rev. Canon Ralph Creed Meredith. Creed Meredith played singles against Agnes on three occasions (according to the notoriously "iffy" Times search engine) and beat her twice.

First, let's introduce ourselves to the Rev. Canon Ralph Creed Meredith. Creed Meredith played singles against Agnes on three occasions (according to the notoriously "iffy" Times search engine) and beat her twice.Meredith was a cleric and a mason—something that apparently was a bit controversial at the time. According to the blog The hermeneutic of continuity:

"Hannah" was Walton Hannah, an Anglican clergyman, who according to the blog "was later received into the Catholic Church."

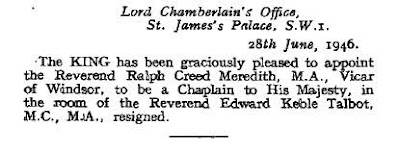

Nonetheless, Creed Meredith served as chaplain to George VI and Elizabeth II [above, right]. On 28 June 1946, the London Gazette published an announcement which offically appointed him "Chaplain to his Majesty." In 1954, his address is listed in Time & Tide Business World (vol. 35) as "The Vicarage, Windsor."

Nonetheless, Creed Meredith served as chaplain to George VI and Elizabeth II [above, right]. On 28 June 1946, the London Gazette published an announcement which offically appointed him "Chaplain to his Majesty." In 1954, his address is listed in Time & Tide Business World (vol. 35) as "The Vicarage, Windsor."I'm admittedly unsure how that combined vicarage and appointment [Would this have been simply a title, Honorary Chaplain to the King (K.H.C.)?] relate to the being a chaplain at the Queen's Chapel of the Savoy, where Reverend Barton R. V. Mills served as an assistant chaplain from 1901 to 1908. Nevertheless, it was a likely conversation starter for the Mills siblings with the Reverend Canon. You'll remember that Barton Mills was involved in the official ceremonies at the funeral of Queen Victoria and stayed on at the Savoy, moving his family, including his daughter Agnes (age 6) son George (age 5) to London in time to be counted in the census. Violet was born in 1902.

Around 1960, Creed Meredith had moved to at 9 Kingsbridge Road, Parkstone, Dorset, according to the Church of England Year Book, volume 85, making him a probable member East Dorset Lawn Tennis & Croquet Club, where he beat Agnes Mills (+12) on 13 September 1960. The aging vicar, then 73, fell to her (-4) on 11 July 1961 on her home lawns at the Budleigh Salterton Croquet Club.

According to RootsWeb at ancestry.com, Creed Meredith was "was born 10 Jul 1887 in Dublin, Ireland, and died Jan 1970 in England. He married Sylvia Ainsley [on] 21 Apr 1915, daughter of Joseph AYNSLEY. She was born 16 Aug 1894 in Blyth House, Blyth Bridge, Stoke-on-Trent, and died 20 Sep 1987."

Another fellow the Mills knew on the lawns, one whom we first met yesterday, was Sir Leonard Daldry. The Times archive has himm playing with and against them in croquet twice, under unusual circumstances.

Another fellow the Mills knew on the lawns, one whom we first met yesterday, was Sir Leonard Daldry. The Times archive has himm playing with and against them in croquet twice, under unusual circumstances.On 10 May 1968, Sir Leonard was victorious over George Mills (+2 on time). Later in the day, he beat George again. In a doubles match, playing alongside Violet Mills, he defeated George and his partner Barbara (Mrs. H. F.) Chittenden (+12), the Mills siblings scoring both a tournament win and loss in the same tilt. Although I'm uncertain exactly how doubles pairings were created at the time, one can assume the Sir Leonard knew at least two of the Mills somewhat well for at least that one day!

Daldry was born on 6 October 1908 and died at the age of 80 in October 1988 in Swindon, Wiltshire, 25 or 30 miles south-southeast of the Cheltenham Croquet Club. The Mills siblings played in croquet tournaments in Cheltenham at least three times, two in 1961 and 1965, during both of which it's possible that Sir Leonard was not in Nigeria.

The National Portrait Gallery describes Daldry in this way: "Sir Leonard (Charles) Daldry (1908-1988), Banker and Senator of Federal Legislature, Nigeria." He is a sitter in 18 portraits taken by the famed photographer "Bassano." In some portraits, Daldry appears with his wife, Lady Joan Mary Daldry (née Crisp). Those were taken on 30 October 1963. He later had individual portraits taken by Bassano on 23 April 1976. Disappointingly, none of these portraits are available on-line. Presumably, they may be of slighly higher quality than the image of Daldry [above, left] I was able to crop from an on-line 1974 MacRobertson Shield teams photograph.

According to Nigerian Wiki: "Leonard Charles Daldry was resident director of the Barclay's Bank for West Africa and later that of Nigeria and the Cameroons. He joined the bank in 1929. In the 60s, he was chairman of the Nigerian Barclay's bank." He is also listed there as a member of the Nigerian First Republic Senate.

On 1 January 1960, Daldry was appointed to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire "for public services in the Federation of Nigeria," according to the London Gazette.

On 1 January 1960, Daldry was appointed to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire "for public services in the Federation of Nigeria," according to the London Gazette.Daldry is also described as "Nigeria Board of Barclay's Bank, DCO... a member of the Nigerian Railway Corporation [and] a Special Member of the House of Representatives and as a Senator, 1929-61," in Accessions to repositories and reports added to the National Register of Archives by The Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts in the National Register of Archives (Great Britain, 1969).

It seems that Daldry was intimately involved with Nigeria's economics and governance before and slightly after it gained its independence from Britain on 1 October 1960.

He certainly must have had a great many stories and insights to share on the lawns and at the bar in various croquet tournaments around England.

There is a third name of interest among the players during my "Mills Era" of croquet in south England: Lady Ursula Abbey.

We'll save Lady Ursula for another day, for reasons that we'll find out soon. Stay tuned...

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)