Let's take a bit of a break from profiling

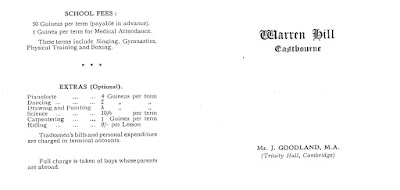

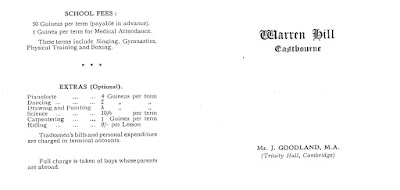

Joshua Goodland, once head master of

Warren Hill School [left] in

Meads, and take a look at another interesting document I've just received from the

Eastbourne Local History Society. This folded leaflet promoting the school won't allow us to stray far from our look at the life of Goodland, however.

Dating from around 1930, it describes the Warren Hill of J. Goodland in a way that the images we've seen simply could not. As an American, I'm somewhat familiar with what life in a preparatory school might have been like—after all, I've seen

About a Boy and

Dead Poet's Society—but this brochure certainly describes the campus, education, and recreation far more clearly than I could have imagined it. Can I assume Warren Hill was fairly typical of a southern prep school of the era between the World Wars?

I realize this pamphlet [right; click to enlarge] was intended for parents and does not discuss specific institutional policies, classroom procedures, rules of conduct, rewards, or punishments that may have been of far greater interest to the children.

We can, however, by reading the books of

George Mills, surmise what a term would have been like at Warren Hill (or not-too-distant Windlesham House) from the boys' point of view. His keen "eye" and "ear" describes not only the appearance and jargon of the boys at what Mills felt was a "modern" preparatory school (very much in contrast, I suspect, with his own school days), but also the daily routine—and breaches of that routine—in an exceptional manner.

We can enter the headmaster's office for punishment and are privy to the reactions of boys who take it well and learn from it, as well as lads that the tennis shoe only embitters. We can prowl through empty classrooms after hours, practice our cricket and football, defend our classmates, pretend we're asleep after hours, deal with bullies and practical jokes, do homework, and even get a peek into the back room where a hot and thirsty schoolmaster could draw himself a pint of beer and catch a quick nap!

As we can see [left], Mills was no longer in the employ of Goodland and Warren Hill by 1930, probably when this document was printed, but he likely had been at least an instructor of Junior French, as well as possibly English. The "novice schoolmaster" character in his books,

Mr. Mead (the name probably a tribute to his beloved Meads), taught French—although many of the children in his books liked Mr. Mead anyway—and

Windlesham House School believes he taught "English and English subjects" in Brighton.

As a teacher, he was able to make keen observations. As a writer, he was able to weave them into insightful, humorous, and believable narrative.

This leaflet helps to flesh out our concept of Warren Hill, and I am indebted to the ELHS for all of their assistance. At first they

provided photographs of the edifice itself, and

recently populated the campus with images of people associated with the school—and even a dog,

Tiny!

This current document serves to enhance further our knowledge of Warren Hill School as a modern institution with a variety of educational, social, and recreational curricula.

Upon sending it, ELHS member

Michael Ockenden added:

"The dancing teacher, the cricket coach, and the gymnastics and boxing instructor were not permanent staff. They were all residents of the town who worked at various schools. The same was probably true of the piano teacher although I don't see her name among the piano teachers in my 1940 trades directory. Mr Moss had a gymnasium in Meads (Derwent Road) which was used by many of the private schools in the area."Thank you so much, Michael!

At one time, at least for me,

"Warren Hill School" was simply a short sequence of relatively meaningless words in the dedication to largely forgotten children's book,

Meredith and Co., a text inspired by the adventures (and one supposes misadventures) of George Mills while teaching at Warren Hill School, with illustrations of the setting and characters [right] conceptualized and rendered by the legendary

C. E. Brock.

Many thanks once again to

everyone who has made it all become real for me, and who has helped me to so often visit Eastbourne vicariously and begin to know this school far better than I ever thought I would!

The jacket and frontispiece are not full colour: It uses a two colour separation (blue and yellow) with black line. The artist isn't renowned. In fact, he is a mid-20th century illustrator in search of a Christian name: P. White.

The jacket and frontispiece are not full colour: It uses a two colour separation (blue and yellow) with black line. The artist isn't renowned. In fact, he is a mid-20th century illustrator in search of a Christian name: P. White.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)