My brother and his wife are in town from Michigan, so I don't have as much time as I might to write. Last night we pounded pizza dough and baked our own pizza pies in the oven. Tonight: Off to the Thai restaurant [left]!

Meanwhile, here are a few questions that still bounce around in my head, in no particular order:

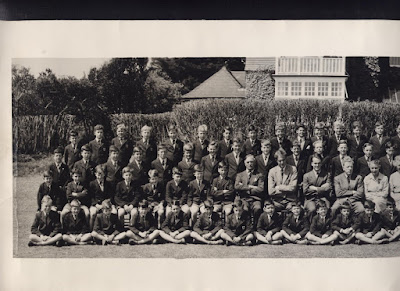

• When George Mills taught at Ladycross School in Seaford in 1956, at the approximate age of 60, was he still regularly working as a master, or simply acting as a substitute?

• Is the "Eaton Gate Preparatory School" he mentions in his dedication to the 1938 version of King Willow now known as Eaton House Belgravia—and why won't they answer enquiries regarding that?

• What would a young man of 16 have done with the next four years if he left Harrow School in 1912 and didn't go off to war until 1916? That's what George Mills had done.

• When did Elizabeth Edith Ramsay Mills, mother of George, pass away?

• When did Barton R. V., Elizabeth, George, Agnes, and Violet Mills move in with Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay?

• Were Agnes and Violet living with George in Devonshire when he died in 1972? Or did they perhaps move into his place after he passed?

• Why can't I find a place called "Greyfriars, Budleigh Salterton, Devon"?

• How long did George Mills teach at Warren Hill School?

• When George returned to the southern coast in 1935, he visited a "Mrs. Charles, then in Springwells, Steyning, W. Sussex." Could that have actually been "Mrs. Charles Scott Malden," wife of the former principal of Windlesham House School?

• When George returned to the southern coast in 1935, he visited a "Mrs. Charles, then in Springwells, Steyning, W. Sussex." Could that have actually been "Mrs. Charles Scott Malden," wife of the former principal of Windlesham House School?• Why did Barton R. V. Mills leave the vicarage at Bude Haven, Cornwall?

• Why did Barton R. V. Mills leave the Chapel Royal of the Savoy?

• What is in the obituary of Vera Louise Beauclerk Mills, who died in 1942, Barton Reginald Vaughan Mills, who died in 1932, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, who died in 1955, and Lady Dorothy Walpole Mills, who died in 1959?

• And, most of all, what is in the obituary of George Ramsay Acland Mills, who passed away in 1972?

I'm just thinking out loud, but if you have any thoughts, please let me know, and thanks!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)