Last time we took a look at the early life of

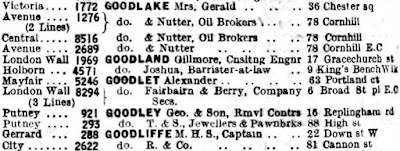

Joshua Goodland, but since we left him at 9 King's Bench Walk in the Temple district [left], I've discovered a few more documents that provide additional insight into those years.

On a 1907 ship's manifest, there is a record, very difficult to discover, that clearly shows school mates Goodland,

Vyvyan Holland, and

Peter Wallace all entering Canada bound for Quebec. Undoubtedly, this is the trip that Holland referred to in his autobiography in our last posting. The trio of friends departed Liverpool on 22 November 1907 sailing on

The Victorian and arrived at Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 29 November 1907 for immigration purposes before traveling on to St. John's, New Brunswick.

Each listed his final destination as Montreal. Little else is recorded on this document save the fact that two "saloon" passengers who traveled with the three were deported. The documentation of the occupants of steerage, however, is rife with information about each individual. It's apparent a sort of class system was functioning that day as

The Victorian put into port at 4:45 p.m.

In addition, a record in the book of

Cambridge University Alumni, 1261 – 1900, provides the following information:

"Adm. at TRINITY HALL, 1900. S. of Gillmore, deceased, of Exmouth, Devon. [B. July 17, 1873.] School, Combe Down, Bath. Matric. Michs. 1900; B.A. and LL.B. 1904; M.A. 1907. Called to the Bar, Inner Temple, June 12, 1907. On the North Eastern Circuit. A law ‘coach’ in London. F.R.G.S. During the Great War, 1914-19, legal adviser to the Priority Dept., Ministry of Munitions; M.B.E." That was found under the entry

"Joshua Goodland," and further categorized by

"College: Trinity Hall," and

"Entered: Michs 1900." It further provides his date of death at this point, but that would be getting ahead of our story!

Examining the rest of the entry above, it provides some information we already know: Joshua was the son of

Gillmore Goodland of Exmouth, Devon. We do learn, however, the exact date of his birth: The

17th of July 1873.

Goodland seems to have attended school in

Combe Down, Bath, Somersetshire. Presumably this school is still there, now known as the

Combe Down Junior School [right], which was constructed the Gothic style in 1840 and enlarged in both 1887 and around 1900. With Goodland having been born in 1873, the first enlargement would have been started when he was 15—a time when he, indeed, could have been attending.

We know Goodland, 7 years old, was at home in 1881 and is listed on that year's 3 April census as a

"scholar." It isn't unreasonable to think that young Joshua was first a student in his father's own school; the senior Gillmore, as we know from the same document, was a

"Certificated Teacher [at an] Elementary School." Goodland's next level of education likely came relatively soon after. The 1891 census, taken on 5 April, describes Goodland as a

"school teacher's assistant," although he was at home with his mother when the census taker arrived.

After having thought that Joshua's father might have been at school that day, it turns out that Gillmore, Sr., was in the Rose Hill section of Worcestershire at 3 St. Mary's Terrace visiting 77-year-old widow

Esther Willets and her companion,

Jane C. Scarfe, 42. Next to

"companion," however, someone else has clarified the entry by writing,

"Dom." Presumably that means "domestic," as it is also written next to the occupation of

"nurse," which described 50-year-old

"servant" Lucian Dowell. There were two other servants in the home at the time, a cook and a housemaid.

Willets was described as

"living on her own means." Goodland, 49 at the time, is described as a

"1st class certificated teacher," next to which a different hand had boldly written,

"School." The senior Goodland would pass away in 1893.

What occupied Joshua between 1891 (and especially following the time of his father's death in 1893) and entering Trinity Hall [left], Cambridge, at Michaelmas in September 1900, was at first unknown. We did have a clue, though. In the 1901 census, taken that year on 31 March, just 5 months after beginning at Cambridge, you will recall Goodland, then aged 24 years, was visiting a building contractor in Bristol, and Joshua's occupation is listed as

"architect." In fact, Goodland is mentioned in a 2001 text,

Directory of British Architects 1834 – 1914, Volume 1: A – K, by

Antonia Brodie (Royal Institute of British Architects, 2001) . Architect

Edgar John Pullar (1876 – 1929) is listed as having been Goodland's assistant in 1899. There is no listing for a Joshua Goodland in the book's first volume, though, perhaps simply meaning that Goodland never had become a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

It is unclear

exactly what sort of qualifications might have been required. Pullar, according his listing, had

"attended King's College, London 1892." Seemingly more important is the next line:

"Articled to Charles James Chirney Pawley (b. 1854) 1893 for 5 years." Pullar then served as

"Assistant to Arthur Green (d. 1904) 1898-99, and to J. Goodland 1899." Finally,

"Passed qualifying exam 1901." Would I be wrong in assuming that Goodland had been "articled" to someone himself, perhaps for 5 years during the time between the 1891 census and entering Trinity Hall in 1900?

In an 1897 item entitled "The Intermediate: Newly registered students," the

Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, volume 4, listed the results of the Intermediate Examination held in London, Manchester, and Bristol on 15th, 16th, and 17th for probationers

"ult." March in 1897. Below, the article states:

"The following candidates passed and are registered as students:… GOODLAND: Joshua [Probationer 1893]; 1, The Parade, Roath, Cardiff [Master: Mr. G. E. Halliday*]." (The asterisk indicates that Halliday was a member of the Institute.)

Goodland apparently served with

George Eley Halliday (1858 – 1922), an architect whose office was at 19 Duke Street in Cardiff until 1897, and 14 High Street in Cardiff, Wales, in 1897. Halliday is also listed as having

"The Hermitage, Llandaff, South Glamorgan, Wales," as his address in 1897. Halliday, just months after Goodland's examinations, became a member of the FRIBA on 14 June 1897 and later was listed in

Who's Who in Architecture in 1914.

Goodland had taken "The Intermediate" in March of 1897, implying that there must have been a final examination to come. In its "Register of Students," the 1903

Kalendar of the R.I.B.A. simply lists

"GOODLAND: JOSHUA, 1 The Parade, Roath, Cardiff" as having been a student between the years 1893 and 1897.

No mention is made of a final examination—taken by anyone. Pullar's entry above does mention a "qualifying examination," and could that have been "The Intermediate" that Goodland had already taken? I can find no documentation that Goodland passed a final examination after Marh 1897, although one must assume that Pullar, above, could not have been Goodland's assistant if they were both students—or could he have?

My assumption would be that, for Pullar to have assisted Goodman, the later must have been actively involved in the designing and/or production of architecture. If not, with what, exactly, would Pullar have assisted Goodman?

Nevertheless, their union in 1899 took each man in a different direction: Pullar to a career in architecture, primarily in Asia, and Goodland, within a year, to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, as a 27-year-old student.

Goodland's life's work, even at the relatively tender age of 27 had already gone in two different directions. First, we know he assisted his father at an elementary school in Devon. Upon his father's passing in 1893, Goodland became an assistant to George E. Halliday, a Welsh architect in Cardiff, and seemingly had begun that career. Suddenly, at the turn of the century, Joshua was then off to university.

What did Goodland study there? We don't exactly know—he was calling himself an architect, not a student, during the 1901 census, as well as visiting a contractor at the time—but perhaps he simply was picking up some extra cash doing plans for a builder in Bristol while he studied law. Perhaps, however, he originally intended to and at first

was studying architecture at Trinity Hall.

Either way, Goodland wouldn't stay with architecture. He earned

Bachelor of Arts and

Bachelor of Laws Degrees from Cambridge in 1904, and added a

Master's Degree in 1907. During that time, we know Goodland also had traveled to

"Russia and Sweden" with Wallace and Holland. He was called to the Bar, Inner Temple, on 12 June 1907. Having spent 7 years at Cambridge among dear friends, the almost 34-year-old Goodland moved into yet another vocation:

Barrister at Law.

The

Cambridge University Alumni text mentions that after taking his M.A., Goodland served

"On the North Eastern Circuit." Assuming the text is in chronological order, this must have been when Joshua was a young barrister. Does it also imply that he moved around during that assignment? Joshua having become a fellow of the

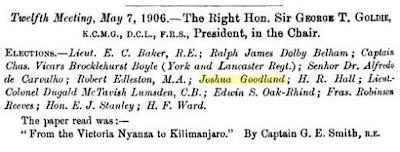

Royal Geographical Society (F.R.G.S.) in 1906 [Its interior is shown, left, in 1912] would seem to confirm the implication that traveling didn't bother him much.

And, as we know, moving around was something Joshua would continue to do. After sailing out of Liverpool on 22 November, he did not return until arriving at Liverpool on 11 August 1908. In between, Goodland had circled the globe while using both his mother's home at Gresham House in London and Inshaw House, London, as his addresses.

The "North Eastern Circuit" must have followed, and then a stint as a

"a 'law' coach in London." One thing notable about Goodland is that, in both architecture and law, he quickly went from student himself to guiding others new to the field.

An easy inference is that Goodland was a natural teacher, an area in which he would have been immersed as the son of and assistant to a schoolmaster.

We know that Goodland married on 19 June 1909 in Middlesex. The fact that Goodland had become a husband in London may imply that he was then—in mid-1909—already serving there as a "law" coach, his time on the circuit having been brief.

A 1946 issue of

The Law Journal (Volume 96) explains:

"It will be observed that there is nothing to prevent a student who wishes to do so from attending a law coach either before or after taking an Intermediate or Final course if he feels that additional preparation for his [examinations]," and in the early 1920's, there was an actual journal entitled

Law Coach, although I can find no record of its existence before 1920 or after the publication of its third volume in 1922 [right, the best I could get].

Goodman appears to have once again begun a trip to the far reaches of the empire, if not around the world, in 1909. He steamed into Brisbane, Australia, from Colombo, Brazil, on the

Oroya on 27 October 1909, presumably on his honeymoon. The actual ship's manifest, however, is not visible at

ancestry.com, and there is an almost exact record, save for the date, for the same ship, the

Oroya, supposedly bearing Goodland, and sailing into Brisbane from Colombo on 3 February 1909.

Was Goodland aboard both voyages? Perhaps he was so enamored of his February 1909 trip to Brisbane that he chose exactly the same shipping line and travel itinerary for a honeymoon later in the year. Perhaps an error in the transcription of the date caused the same arrival to be recorded on two separate dates—and we are not privy to which would be correct since images of the actual manifest have not been provided.

Finally, perhaps it isn't "our" Joshua Goodland at all. Without seeing the manifest, we don't know what other identifying information may have been recorded. However, there simply

aren't any records of other contemporary British "Joshua Goodlands" having been born around 1873. Let's leave it at this: He probably sailed to Australia sometime in 1909.

We've seen some of the litigation in which Goodland was involved in 1912 or so, and we know his London address at the time via telephone records.

The last line of the Cambridge directory we will look at today is this one:

"During the Great War, 1914-19, legal adviser to the Priority Dept., Ministry of Munitions; M.B.E."

The appeals case in the House of Lords between the Water Board, appellants, and Dick, Kerr, & Co., respondents, mentioned in our last post, did, indeed, involve the Ministry of Munitions. Goodland must have been representing them in the capacity of

"legal adviser," as well as junior counsel.

On 7 January 1918, the London

Gazette ran a lengthy list of those

"to be members" of the

"Most Excellent Order." Among the honorees:

"Joshua Goodland, Esq., Classification Section, Priority Department, Ministry of Munitions." [A composite image of the entry is seen, left] In 1917, the M.B.E. had been instituted to be awarded for meritorious service by either military or civilian personnel.

With an upscale address, an MBE to is credit, and an association with high profile London lawyer

Mr. Wm. Danckwerts, KC, on his resume, it's easy to see that Goodland would soon be going places in the legal profession.

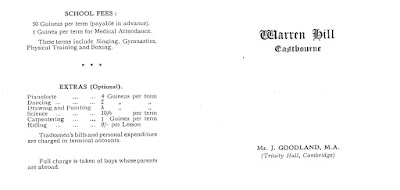

We still haven't brought Joshua Goodland to

Warren Hill School in Meads, however, nor have we associated him with the subject of our interest,

George Mills. Such is the complexity of Mr. Joshua Goodland, Esq., MBE, who was 46 years old in 1919. That year, at the conclusion of the Great War, Goodland left the Ministry of Munitions—and we still are only three vocations deep into his life at this point, with two more professions yet to go!

We'll learn more about the labyrinthine career path of late bloomer Joshua Goodland very soon. Stay tuned…

I realize this pamphlet [right; click to enlarge] was intended for parents and does not discuss specific institutional policies, classroom procedures, rules of conduct, rewards, or punishments that may have been of far greater interest to the children.

I realize this pamphlet [right; click to enlarge] was intended for parents and does not discuss specific institutional policies, classroom procedures, rules of conduct, rewards, or punishments that may have been of far greater interest to the children.  As we can see [left], Mills was no longer in the employ of Goodland and Warren Hill by 1930, probably when this document was printed, but he likely had been at least an instructor of Junior French, as well as possibly English. The "novice schoolmaster" character in his books, Mr. Mead (the name probably a tribute to his beloved Meads), taught French—although many of the children in his books liked Mr. Mead anyway—and Windlesham House School believes he taught "English and English subjects" in Brighton.

As we can see [left], Mills was no longer in the employ of Goodland and Warren Hill by 1930, probably when this document was printed, but he likely had been at least an instructor of Junior French, as well as possibly English. The "novice schoolmaster" character in his books, Mr. Mead (the name probably a tribute to his beloved Meads), taught French—although many of the children in his books liked Mr. Mead anyway—and Windlesham House School believes he taught "English and English subjects" in Brighton.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)